Amidst the clank and hum of construction equipment permeating Calgary’s Beltline, a 115-year-old red brick and sandstone structure quietly awaits its future. The city-owned YWCA building, affectionately known as the “Old Y,” has a history as a hub for Calgary’s activists and artists. But recent changes to its lease agreement with the city have displaced the local groups that have called it home.

Built in 1910 as Alberta’s first hostel for young working women, the Old Y offered a haven for women at a time when few other such spaces existed. It became home to several service agencies in 1972, and it has been known and beloved across many communities in the years since.

The Old Y has functioned as a safe, affordable space for feminist groups to [raise awareness](https://communitywise.n…

Amidst the clank and hum of construction equipment permeating Calgary’s Beltline, a 115-year-old red brick and sandstone structure quietly awaits its future. The city-owned YWCA building, affectionately known as the “Old Y,” has a history as a hub for Calgary’s activists and artists. But recent changes to its lease agreement with the city have displaced the local groups that have called it home.

Built in 1910 as Alberta’s first hostel for young working women, the Old Y offered a haven for women at a time when few other such spaces existed. It became home to several service agencies in 1972, and it has been known and beloved across many communities in the years since.

The Old Y has functioned as a safe, affordable space for feminist groups to raise awareness for women’s health and contraception despite scarce funding, for queer activists to fight for visibility even when newspapers refused to publish their content, and for Indigenous groups to heal the generational trauma settlers continue to inflict.

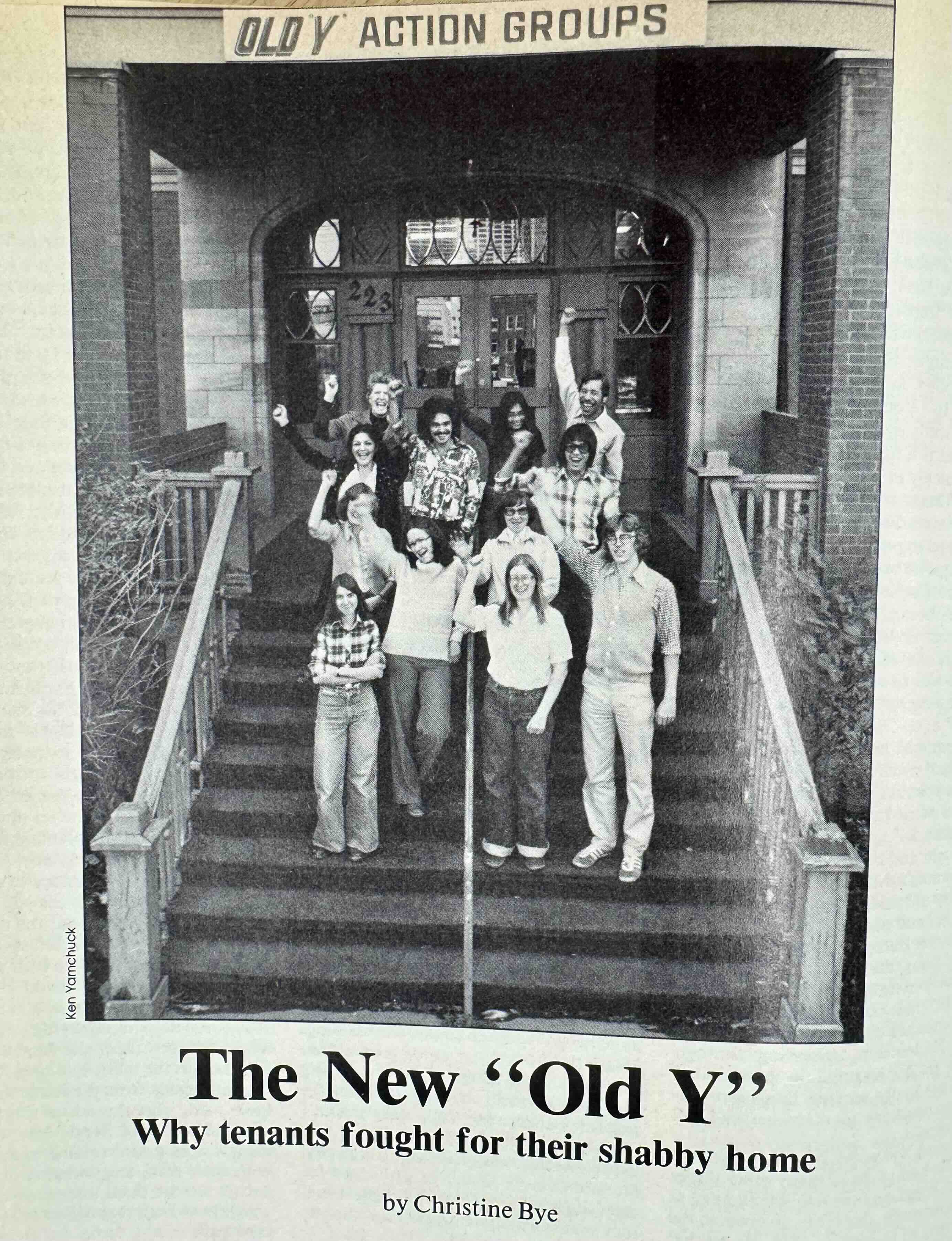

Calgary community organizers, activists and artists stand on the front steps of the ‘Old Y,’ a city-owned building for which Calgary is now seeking expressions of interest from prospective new lessees. Photo via Community Wise Resource Centre on Facebook.

Calgary community organizers, activists and artists stand on the front steps of the ‘Old Y,’ a city-owned building for which Calgary is now seeking expressions of interest from prospective new lessees. Photo via Community Wise Resource Centre on Facebook.

A few weeks ago, the building still nurtured the imagination of the prairie city’s grassroots. Across its three storeys, a maze of narrow hallways bound together Calgary activists, artists and community organizers.

But on Sept. 30, Community Wise Resource Centre, a landlord for those occupying the space, terminated its lease with the city. The move brought the Old Y’s century-old momentum to a halt. While the distinctive Georgian Revival building that housed the Old Y is protected from demolition as a historic site, the community organizations headquartered in the building have no such safeguards. For many, losing access to affordable space in a central location is a threat to their existence. The Old Y is now part of their identity.

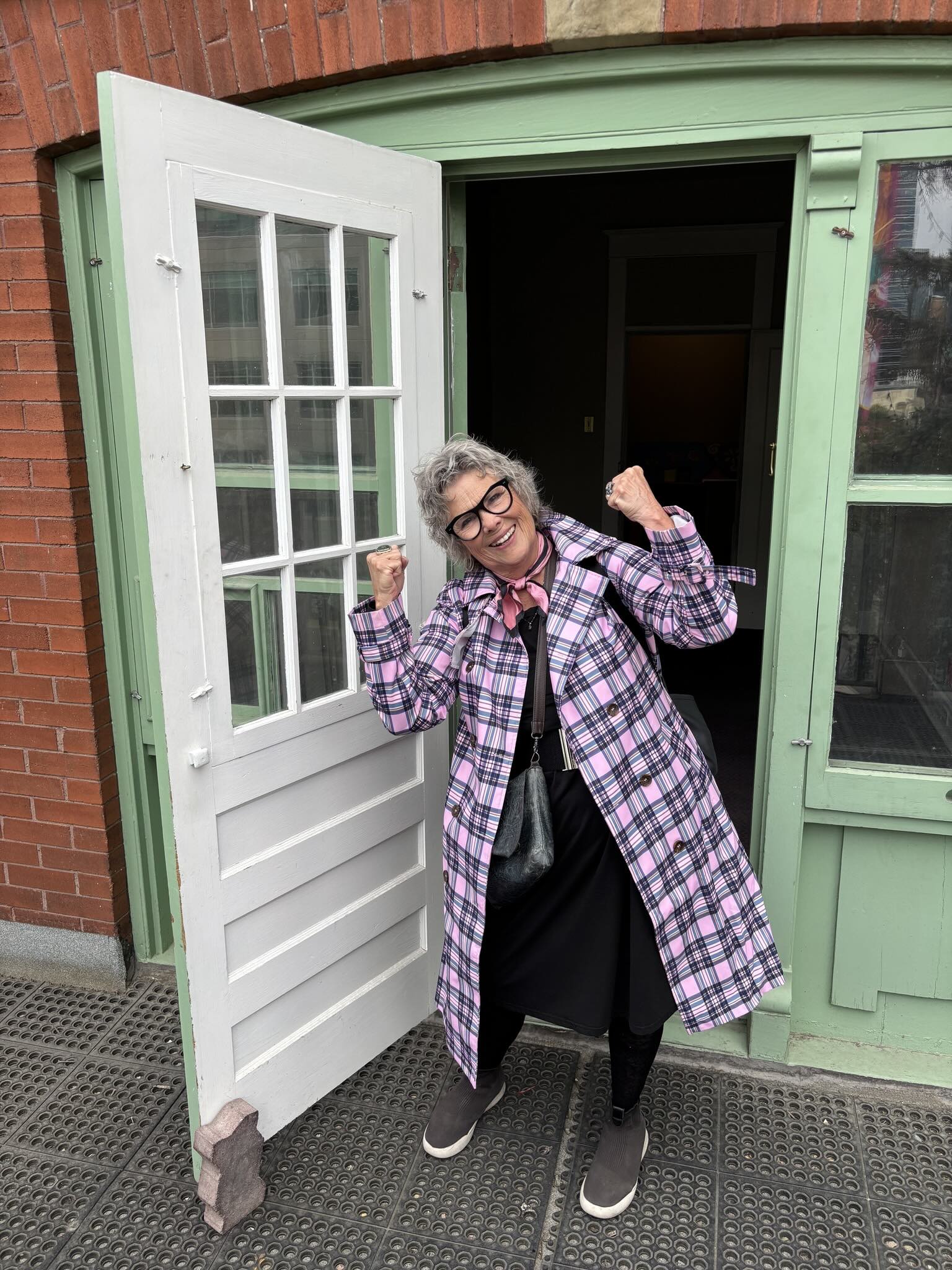

Calgary artist and activist Sharon Stevens rushed to the Old Y to say a final goodbye to the building on its last day at the end of September. Her involvement with the space spans at least 40 years. Photo courtesy of Sharon Stevens.

Calgary artist and activist Sharon Stevens rushed to the Old Y to say a final goodbye to the building on its last day at the end of September. Her involvement with the space spans at least 40 years. Photo courtesy of Sharon Stevens.

Sharon Stevens is a Calgary multimedia artist and activist whose connections to the Old Y span at least four decades. Whether she was collaborating with feminist film organizations to launch initiatives such as herland Film Festival, or working for the Arusha Centre, the building has been a constant in Stevens’ life since the 1980s.

She was leaving her office downtown in late September when she learned that Old Y tenants were about to lose access to the building.

“I just dropped what I was doing and headed to the Old Y,” she told The Tyee. “At five o’clock the key fobs were going to be turned off.”

Stevens rushed to the building, yearning to witness the space as it was.

“It was important for me to walk up the building’s stairs one more time,” Stevens said. “To touch the walls and say goodbye.”

For Stevens, the building is more than a battered relic of a distant past. The Old Y is an everlasting component of Stevens’ identity; it’s a muse that propels her forward.

“I started thinking of the courtyard as the womb of the building, as the incubator, as the place where things are conceived,” she recounted.

“There was no way into it. You had to go down into the basement, into a bathroom, stand on the toilet and crawl through a window — I did a whole performance piece with that.”

A space where people learned from each other

Spending time in tight quarters with fellow community members was essential for the success of the once-small grassroots organizations that, much like Stevens, had their start in the Old Y.

“The activist world builds successes and movements on the shoulders of one another,” Stevens said. “We learned how to create newsletters, how to do all kinds of admin work. We all learned it from each other on the job.”

The former YWCA isn’t the only building where grassroots groups can flourish in Calgary. A number of spaces have been conceived to foster the casual interactions that inspire non-profit workers, activists and artists.

But it’s difficult to design for the kinds of organic connections that made the Old Y special.

“One can no more deliberately design such places that one can plan, with any guarantee of success, the occasions of genuine human exchange,” wrote human geographer Yi-Fu Tuan in his 1971 magnum opus, Space and Place: The perspective of experience.

Writing in 1979 for the Calgary Magazine, Christine Bye explained why the building’s original purpose as a hostel for young women was sorely needed; few other spaces in Calgary rented rooms to women when it opened in 1910.

The ‘Old Y’ was originally operated by the YMCA and opened as a hostel for young working women in 1910. Photo courtesy of Glenbow Archives.

The ‘Old Y’ was originally operated by the YMCA and opened as a hostel for young working women in 1910. Photo courtesy of Glenbow Archives.

“The city’s good landladies preferred gentlemen boarders,” Bye wrote, “Because they didn’t spend all their time doing laundry and wasting coal oil heating their curling irons.”

A look into the building’s more recent history reveals that its significance as a safe haven has endured.

Magazine writer Christine Bye detailed the historical significance of the Old Y in the December 1979 issue of Calgary Magazine. Clipping from Calgary Magazine, December 1979.

Magazine writer Christine Bye detailed the historical significance of the Old Y in the December 1979 issue of Calgary Magazine. Clipping from Calgary Magazine, December 1979.

Since the building became home to service agencies in 1972, queer support organizations have thrived in the Old Y.

It all started in 1973 with the People’s Liberation Coalition, whose legacy continues today through Calgary Outlink.

One of the many iterations of these groups was the Gay and Lesbian Community Services Association, where Kevin Allen volunteered in the 1990s.

Allen spent countless evenings supporting peers, usually over the phone but also in person. He also volunteered with the Calgary Society of Independent Filmmakers. He would go on to become the Old Y’s historian-in-residence in 2012.

“I’ve been to so many meetings from so many organizations over the years, that the layers of memory make the place more resonant,” he said. “If you’ve done so much stuff over so many decades in the same building, it becomes very meaningful to you.”

People frequently decorated the Old Y for community events. Photo courtesy of ACORN.

People frequently decorated the Old Y for community events. Photo courtesy of ACORN.

The memory of past activists and organizers permeates the Old Y. Murals painted by unknown artists brighten the walls of many of its makeshift offices, a visual reminder that the future is a collective effort.

Scribbled on the interior panels of a rickety dumbwaiter, dozens of names — some dating back to the 1920s — are testament of the bond between activists past and present.

On her final visit to the space earlier this fall, artist and activist Stevens left her own mark in the building that changed her. “I lifted up a piece of carpet in the Arusha office and wrote my name on the floor,” she said.

Artist and activist Sharon Stevens writes her name on the floor of the Old Y’s Arusha office on her final visit to the site. Photo courtesy of Arusha Centre.

Artist and activist Sharon Stevens writes her name on the floor of the Old Y’s Arusha office on her final visit to the site. Photo courtesy of Arusha Centre.

The Old Y is also a hallmark of Indigenous reconciliation in Calgary. For many decades, it cradled the efforts of community members helping each other, providing comfort to Calgarians whose presence is seldom welcome in corporatized spaces.

“Some of the most marginalized groups of people are served in the Old Y,” said Michelle Robinson, an Indigenous activist and podcaster. “It’s one of those places that doesn’t carry the religious trauma of a church, even though it originally was a Christian-based YWCA.”

Michelle Robinson drums in front of the Old Y. Photo via Community Wise Resource Centre on Facebook.

Michelle Robinson drums in front of the Old Y. Photo via Community Wise Resource Centre on Facebook.

Like glue, artist collectives and ethnocultural groups filled the tenuous gaps between grassroots organizations whose missions didn’t always overlap.

A cacophony of activities — from speaker series, writing workshops and shared meals hosted on the main floor, to counselling and mentoring sessions delivered in an office furnished with mismatching chairs, to DIY repair booths and art markets set up on the building’s front step — amplified the Old Y’s vibrancy, and emboldened many generations of activists to dream beyond the practical.

“I would take my daughters with me when they were teenagers,” Stevens reminisced. “They participated in their own kind of activist work there — so that family legacy has been carried on.”

An unrecognized battle

Up until Sept. 30, the Old Y remained part of Calgary’s present, a vessel of hope for the city’s grassroots — but not all Calgarians know this. Since the 1940s, the prevailing narrative has been that the building is prime for the wrecking ball.

Rescued from demolition first by the City of Calgary and later by the grassroots organizations that leased the space, the Old Y has been repeatedly portrayed as a collection of ailments, its aging body no longer meeting the standards set by engineers and fire departments.

After the city acquired the property in 1971, the Old Y became a bottomless pit in the imagination of many taxpayers. This drove a lack of long-term stability for the service agencies headquartered in the space, as each year politicians pondered what to do about the old building.

‘The biggest stumbling point in the history of the centre has been to convince taxpayers that they have a vested interest in maintaining the building,’ wrote Lois Ross in a May 1978 article for the Calgary Herald. Clipping from Calgary Herald, May 16, 1978.

‘The biggest stumbling point in the history of the centre has been to convince taxpayers that they have a vested interest in maintaining the building,’ wrote Lois Ross in a May 1978 article for the Calgary Herald. Clipping from Calgary Herald, May 16, 1978.

In May 1978, Lois Ross, then a staff writer with the Calgary Herald, succinctly laid out the challenges facing the Old Y.

“The biggest stumbling point in the history of the centre has been to convince taxpayers that they have a vested interest in maintaining the building,” she wrote. “Groups are disillusioned because their battle is unrecognized by the public. They see Calgary taxpayers as conservatives in their support.”

It wasn’t until 1979 that the building’s tenants came up with an idea that would afford them some stability: taking full responsibility for the Old Y.

“What saved the building was the tenants’ own heightened concern over its fate,” Pat Rice, a staffer at the city’s social planning department, told Calgary Magazine in 1979.

“Before, it had been a kind of hand-to-mouth operation. There was no definition as to whose responsibility it was to keep the building up from year to year. But when the tenants became really keen on putting some effort into it themselves, we got really keen, too.”

In the collective memory of its former occupants, however, the Old Y lives on as a source of creative nourishment, rather than as a headache to be quashed.

One former tenant who wished to remain anonymous, an organizer with the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, or ACORN Canada, compared the Old Y to a mother tree sharing resources with saplings across the forest.

A winter party in the Old Y’s common room, 2024. Photo courtesy of Arusha Centre.

A winter party in the Old Y’s common room, 2024. Photo courtesy of Arusha Centre.

A place that said, ‘Come as you are’

The future of the building will be determined by the capacity of its next lessee, and the City of Calgary is currently seeking expressions of interest that are open for another month, until Dec. 1.

The Arusha Centre plans to submit a proposal to continue the legacy of the space, but it’s a costly undertaking; building service requirements, upgrades to meet modern code requirements and lifecycle costs are listed on the property sheet and estimated to cost at least $30 million.

Historically low rents at the Old Y helped make it the grassroots hub that it was; the rents enabled volunteers to lend a hand to their peers at no cost. The Beltline location allowed Calgarians of all walks of life to come into the building without hesitation. People who might not have otherwise encountered each other converged as equals — and came out ready to change the world.

Unlike the cost of repairing and maintaining the historic building, however, the organizers serving Calgarians in the Old Y seldom made news headlines.

But the stories we tell about the places we cherish matter, especially when they diverge from mainstream narratives. “Past events make no impact on the present unless they are memorialized,” human geographer Tuan wrote in Space and Place: The perspective of experience.

“There is something really special about being in such close proximity to so many types of services, supports, and ideas,” Emma Ladouceur, director of operations at Calgary Outlink, told The Tyee.

“To have a space where you can just show up exactly as you are and be welcome is really powerful.” ![[Tyee]](https://thetyee.ca/design-article.thetyee.ca/ui/img/yellowblob.png)

- Share:

- **