In 1989, Toronto-based activist artists Carole Condé + Karl Beveridge created a photographic work that addressed free trade between Canada and the United States. Titled Free Expression, it renders free trade as a visible force pulsating through the world in the form of a signal from a radio tower perched atop the planet. In the foreground, a man and a woman interrupted sit at a desk piled with Canadian publications. The perspective is skewed to provide an aerial view of their desk, revealing a slew of alternative literary magazines.

The scene is set for confrontation. While the older man looks over his shoulder apprehensively, the seated woman gazes directly at viewers, drawing them in. Behind her, another woman stands wit…

In 1989, Toronto-based activist artists Carole Condé + Karl Beveridge created a photographic work that addressed free trade between Canada and the United States. Titled Free Expression, it renders free trade as a visible force pulsating through the world in the form of a signal from a radio tower perched atop the planet. In the foreground, a man and a woman interrupted sit at a desk piled with Canadian publications. The perspective is skewed to provide an aerial view of their desk, revealing a slew of alternative literary magazines.

The scene is set for confrontation. While the older man looks over his shoulder apprehensively, the seated woman gazes directly at viewers, drawing them in. Behind her, another woman stands with her arm outstretched and hand raised to stop a column of men from marching into the room. Free Expression depicts an impending conflict between cultural producers. Three of the intruders wear business attire, their heads replaced by media images, including Fortune and Time magazines as well as a television set showing George H. W. Bush, then president of the US. The floor behind them tilts radically, disrupting the perspective of the image. A framed photo of then prime minister Brian Mulroney hangs on the wall, slightly askew, a ghostly glow illuminating his face.

Produced as a postcard, Free Expression circulated widely inside an issue of Fuse. It is one example of how free trade inspired the production of art that reflected the new trade agreements as well as changing ideas about North America. In the face of the economic power of the US, the photo depicts a nation-based struggle. It affirms the category of Canada, naturalizing Canadian culture and depicting Canadian cultural production as pitted against US cultural hegemony.

Many other artworks about free trade produced during this period took this stance. Like Free Expression, these works tackle and reveal the debates over trade that polarized Canadian and North American society near the end of the twentieth century. They show the cultural dimensions of a mechanism typically assessed only from economic perspectives.

In many ways, North America in the early twenty-first century appeared as a unit consisting of three geographically proximate nations linked by economic, political, and cultural ties. In fact, this unit had to be created, because prior to the late twentieth century, North America was not conceived of in this way. Instead, the Americas were understood as divided between Anglo and Latin America. Canada and Mexico were each preoccupied with the US and did not develop strong ties to each other.

Art was vital to naturalizing the economic unity achieved in the free trade deals. Exhibitions and cultural initiatives were key means by which new ideas of North America were messaged to the public. The Canadian, Mexican, and American governments employed art shows to demonstrate their shared interests. For instance, Panoramas: The North American Landscape in Art is notable as the first online exhibition supported by the three nations. It employed landscape art as a means to project a message of unity. When it opened in 2001, it was celebrated with events in each country, linked by a three-way digital video conference.

Its origins are notable. Coordinated by the Canadian Heritage Information Network, Panoramas united four North American partners: the Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG), the Canadian Museum of Civilization (CMC, now the Canadian Museum of History), the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), and Museo Nacional de Arte (MUNAL). Several other cultural organizations also contributed. It featured over 300 pieces by artists from all three countries, approximately a hundred of which were Canadian, drawn from the permanent collections of the CMC and the WAG. The exhibition also represented an extensive range, with works spanning 200 years.

Panoramas slotted national landscapes into a North American framework, severing the traditional connection between landscape and nation. The featured works included many iconic pieces, which retained a semblance of their past meaning, but they were displayed in a manner that emphasized continental associations. Canadian artists included Tom Tomson, Edwin Holgate, and Alex Colville; Mexican artists included Frida Kahlo, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Diego Rivera; and American artists included Winslow Homer and Georgia O’Keefe. A small flag indicated the national origin of every work, but each one also included a hyperlink that, when activated, opened a map of North America. In this way, national associations were maintained, but continental perspectives were emphasized.

Panoramas was designed as a multi-faceted platform to educate the public about North American integration, deemed necessary because of the economic integration of the new North America under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Its political origins reveal the interest of the three governments in teaching their citizens about the connections between their countries. Panoramas, thus, upheld and constructed a North American landscape that was in accordance with NAFTA requirements.

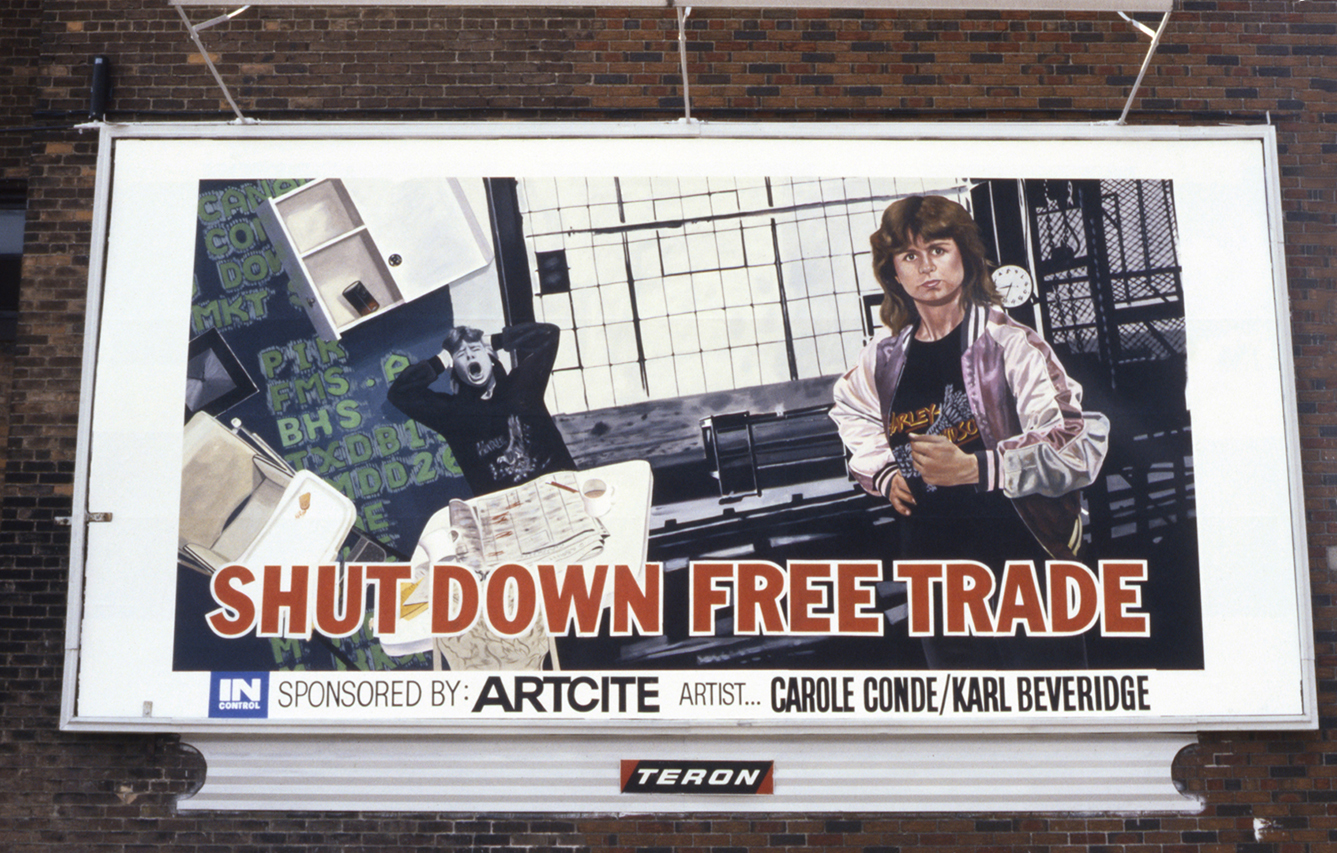

Paradoxically, art also offered a venue for dissent against this same economic unity. Works such as Free Expression by Condé + Beveridge frankly express apprehension regarding free trade and visualize its potential impact on the art community, revealing concerns about American cultural imperialism. The artists revisited these issues in subsequent works, including Shutdown (1991), which depicts the impact of the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA) on Canadian labour. Shutdown centres on the frustrations of a worker who has lost her job due to free trade. At the left, a fractured domestic interior alludes to financial hardship, and a black-and-white image of an empty factory fills the right side of the picture. Underscoring the stakes for workers, the artists personalize the impact of free trade, pointing to the struggles of an individual.

Shutdown (1991) by Carole Condé + Karl Beveridge as a painted billboard in Windsor, Ontario (originally a photographic image)

Shutdown (1991) by Carole Condé + Karl Beveridge as a painted billboard in Windsor, Ontario (originally a photographic image)

The photograph was installed as a painted billboard in Windsor, Ontario, and was viewed against the Detroit skyline. This placement brought it into the public sphere, where it explicitly commented on those who were directly affected by free trade, enhanced by the Windsor region’s close ties to the North American auto industry.

Panoramas and Shutdown speak to congruent aspects of the larger issue—art’s role in creating North America, whether as an integrated whole (as envisioned under NAFTA) or as separate national domains (by resisting the dominance of the North American imaginary). Art became a vehicle for the state to manufacture consent—and for cultural producers to express dissent.

Two short videos from 2001, Packin’ by John Greyson and Like a Nice Rubber Gas Mask by Malcolm Rogge, make powerful statements about the potential of art as a form of activism. Both responded to the protests at the April 2001 Summit of the Americas in Quebec City. Comprised of three days of meetings between leaders from North and South America, the summit was the site for negotiations toward a proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), which had been announced in 1995 as a means of uniting all the nations of the Americas (with the exception of Cuba) through the elimination of barriers to trade.

The summit was to have been the occasion when heads of state and delegates agreed to a draft document, but the process subsequently stalled, and by 2005—the initial deadline for its implementation—the FTAA had failed. The summit was marked by a large complement of peaceful protesters, who objected to neoliberal globalization and the extreme security measures in Quebec City.

Packin’ and Like a Nice Rubber Gas Mask were part of a larger compilation of thirteen videos assembled by the Blah Blah Blah Collective. The collective took its name from a widely publicized remark by then prime minister Jean Chrétien, who dismissed protesters at the summit as misguided pleasure seekers. Chrétien scoffed to the media, “They say to themselves, ‘Let’s go spend the weekend in Quebec City; we’ll have fun; we’ll protest and blah, blah, blah.’”

In the face of such scorn for citizens’ rights, the collective stipulated that funds generated by screenings of its video compilation would go to offsetting the legal fees of protesters who were arrested in Quebec City. The videos addressed the history of free trade’s implementation, recording the significant public backlash to the agreements.

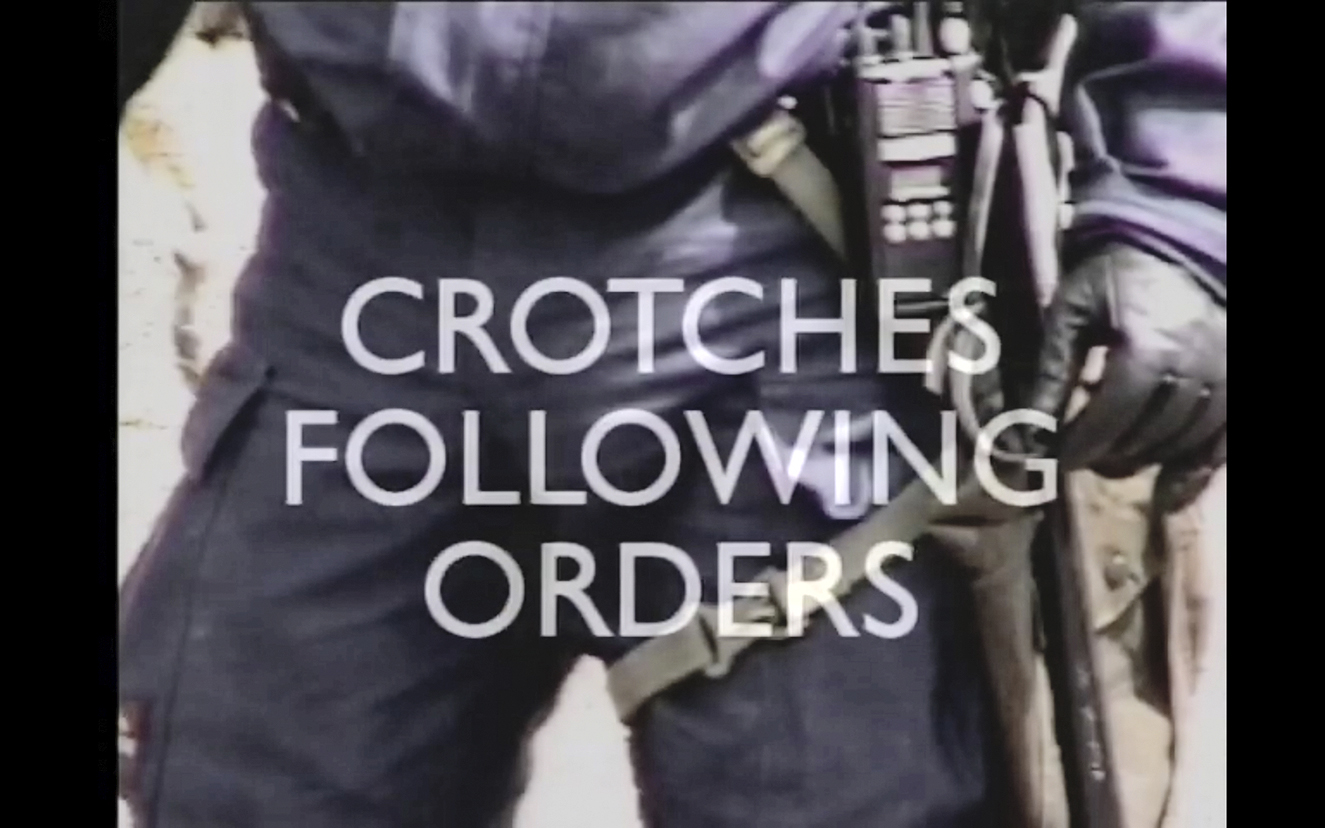

Through a tongue-in-cheek documentation of the crotches of cops and politicians, Packin’ focuses on the heavy police presence in Quebec City. In his artist statement, director John Greyson describes the four-minute work: “Bored crotches, nervous crotches, violent crotches: a unique view on the overwhelming police presence that tear-gassed a city.”

These phallic references speak to patriarchy and power. The Quebec summit was notorious for its number of police officers—“the largest police deployment in Canadian history”—and included security measures that transformed the city, such as chain-link fencing and concrete barriers, as well as water cannons, tear gas, smoke bombs, and rubber bullets. The crotches in Packin’ are interspersed with text panels commenting on the police presence and on government.

A video still from Packin’ (2001) by John Greyson

A video still from Packin’ (2001) by John Greyson

Intertitles describe the crotches as national crotches, provincial crotches, undercover crotches, corporate crotches, canine crotches, crotches following orders, and more. The fast pace of the video can be disorienting, as the text frames quickly scroll up the screen, intercut with shots of the protest landscape, including police, politicians, and chain-link fencing. Greyson queers the state apparatus, revealing its heteronormativity and highlighting the connections between body and power. Rather than defending national culture, Greyson concentrates on the power accorded to police and politicians, suggesting that free trade is advanced by hegemonic forces.

Greyson’s approach reflects artists’ ongoing investment in the struggle against free trade. The videos from this period oppose larger structures, of which free trade agreements were but a symptom. No longer tied to anxieties around the nation-state and the new North America, Packin’ acknowledges the influence of neoliberalism and the disempowerment of citizens in the face of militarized police control. It shows that artists positioned free trade within existing power structures—through a broader social criticism of the system in which free trade functions.

Malcolm Rogge also approaches the Quebec City protests with humour in Like a Nice Rubber Gas Mask, a title that references the creative attire of the protesters who came to town for the summit. Four minutes and thirty seconds long, it parodies street fashion segments on television programs by interviewing the activists about what they are wearing. The protesters are not wearing clothes with designer or corporate labels. Emphasizing this absence, in a nod to red-carpet media coverage that is notorious for the question “Who are you wearing?”, Like a Nice Rubber Gas Mask asks protesters to describe their outfits. One replies, “The look is red. Red is the hot colour of the season. Everybody is wearing it.”

Many of the “fashion” items are repurposed from conventional uses. For example, many people wear goggles to protect their eyes from tear gas. One comments, “Goggles are in. Day or night, swimming, non-swimming. Any time of the day.” An old-fashioned gas mask is “retro.” Some demonstrators wear red clown noses, and many use wit as a protest tactic. Costumes reinforce the non-violent nature of the gathering. In another encounter, a protester attired in kitchen gear is asked, “Hey you, with the colander. Any words for fashion in 2001?” The swift reply is, “Well your biggest fashion statement is going to be the wooden spoon, to stir shit up!”

Rogge employs a popular-culture media format to focus on the demonstrators. Like Packin’, his video is an implicit endorsement of the anti–free trade stance, using levity to catch viewers’ attention while also speaking to larger capitalist systems of consumption. His approach humanizes the protesters, refuting the newspaper articles that focused on the violence and portrayed the activists as homogeneous groups of anarchists.

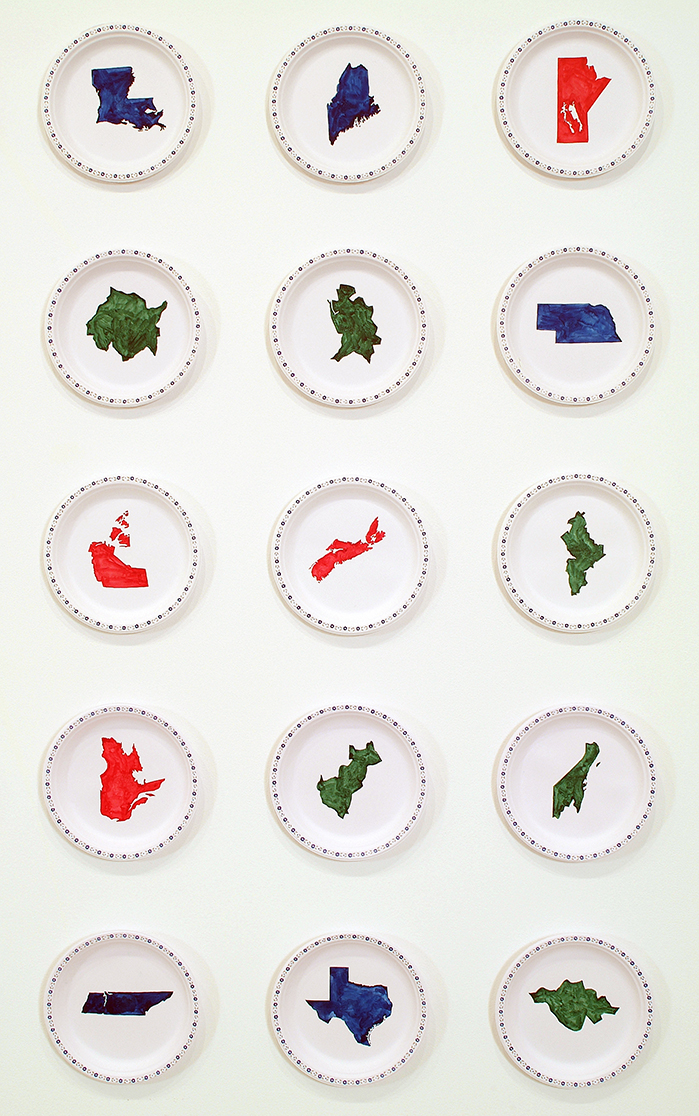

State Dinner, a 2005 installation by Halifax-based artist Peter Dykhuis, was a response to the 1994 implementation of NAFTA. It took shape in an installation featuring the disposable paper plate. Dykhuis chose Royal Chinet plates, with their recognizable blue-and-grey floral border, as the basis for the work. Realized over a decade after NAFTA’s implementation, State Dinner comments on the complexities of mapping place through nation, region, and trade zone, emphasizing the discrete parts of the territory encompassed by the trade alliance, while inverting the pomp and circumstance typically afforded to state diplomacy.

*State Dinner *(2005) by Peter Dykhuis. This photo by Steve Farmer shows the 2007 installation at Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery, Halifax.

*State Dinner *(2005) by Peter Dykhuis. This photo by Steve Farmer shows the 2007 installation at Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery, Halifax.

The installation features ninety-five plates mounted on the wall and arranged in a grid. Each one sports a simple outline map of a province, territory, or state in Canada, the US, or Mexico, carefully rendered in watercolour. The maps are colour-coded to reflect the dominant hue of the three national flags: red for Canada, green for Mexico, and blue for the US. They are arranged in alphabetical order, beginning with Aguascalientes and ending with Zacatecas, further reworking the expected juxtaposition of the locations.

The resulting disordered map of North America functions as an “inventory of its parts” while emphasizing the artificiality of national ties and the disposable nature of regional identity. Underscoring consumption and the economic aims at the core of NAFTA, State Dinner reflects on the superficiality of the integrated free trade zone and comments on what happens when the familiar trappings of national identity are stripped away.

Despite their formal and aesthetic differences, these works chronicle the changing ways that Canadian activist artists grappled with North American integration. The fact that such a varied body of work exists tells us a lot about the complicated relationship between culture and trade.

The complex history of art and free trade is important to acknowledge. Our recent conversations about free trade trouble the perception of North American integration that was developed over many years. After Donald Trump was first elected US president in 2016, he oversaw NAFTA’s revision into a new agreement that was implemented in 2020, which is referred to as the Canada–United States–Mexico Agreement, or CUSMA, in Canada. In the US, it is known as the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, or USMCA, and in Mexico as the Tratado entre México, Estados Unidos y Canadá, or T-MEC. Tellingly, “North American” has been removed from its title, and relations between the three parties have been rebalanced back to the national. The deal is focused on trade; the ancillary activities around NAFTA—the creation and promotion of an integrated North America—are a thing of the past.

Adapted and excerpted, with permission, from Trading on Art: Cultural Diplomacy and Free Trade in North America *by Sarah E. K. Smith, published by UBC Press, 2025. *

Sarah E. K. Smith is an associate professor at Western University, where she holds the Canada research chair in art, culture, and global relations. She is a co-founder of the North American Cultural Diplomacy Initiative and a member of the International Cultural Relations Research Alliance.