In the fortnight I spent onsite at the State Library of Victoria, ‘Sands & Mac’ was mentioned many times. And no wonder. The Sands & McDougall’s directories are a goldmine for anyone researching family, local, or social history. They list thousands of names and addresses, enabling you to find individuals, and explore changing land use over time. When people ask the SLV’s librarians, ‘What can you tell me about the history of my house?’, Sands & Mac is one of the first resources consulted.

The SLV has digitised 24 volumes of Sands & Mac, one every five years from 186…

In the fortnight I spent onsite at the State Library of Victoria, ‘Sands & Mac’ was mentioned many times. And no wonder. The Sands & McDougall’s directories are a goldmine for anyone researching family, local, or social history. They list thousands of names and addresses, enabling you to find individuals, and explore changing land use over time. When people ask the SLV’s librarians, ‘What can you tell me about the history of my house?’, Sands & Mac is one of the first resources consulted.

The SLV has digitised 24 volumes of Sands & Mac, one every five years from 1860 to 1974. You can browse the contents of each volume in the SLV image viewer, using the partial contents listing to help you find your way to sections of interest. To search the full text content you need to use the PDF version, either in the built-in viewer, or by downloading the PDF. There’s a handy guide to using Sands & Mac that explains the options.

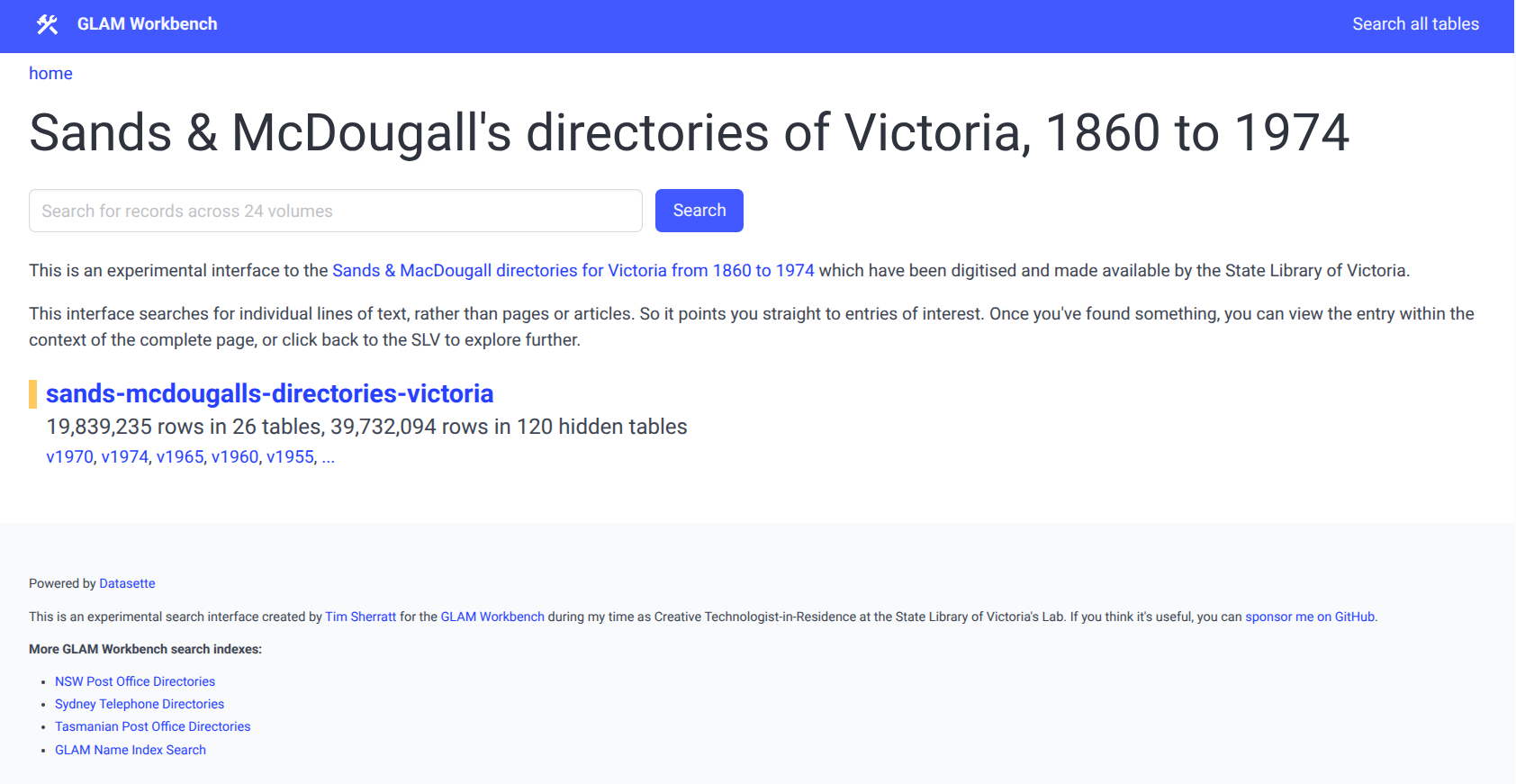

However, there’s currently no way of searching across all 24 volumes, so as part of my residency at the SLV LAB, I thought I’d make one!

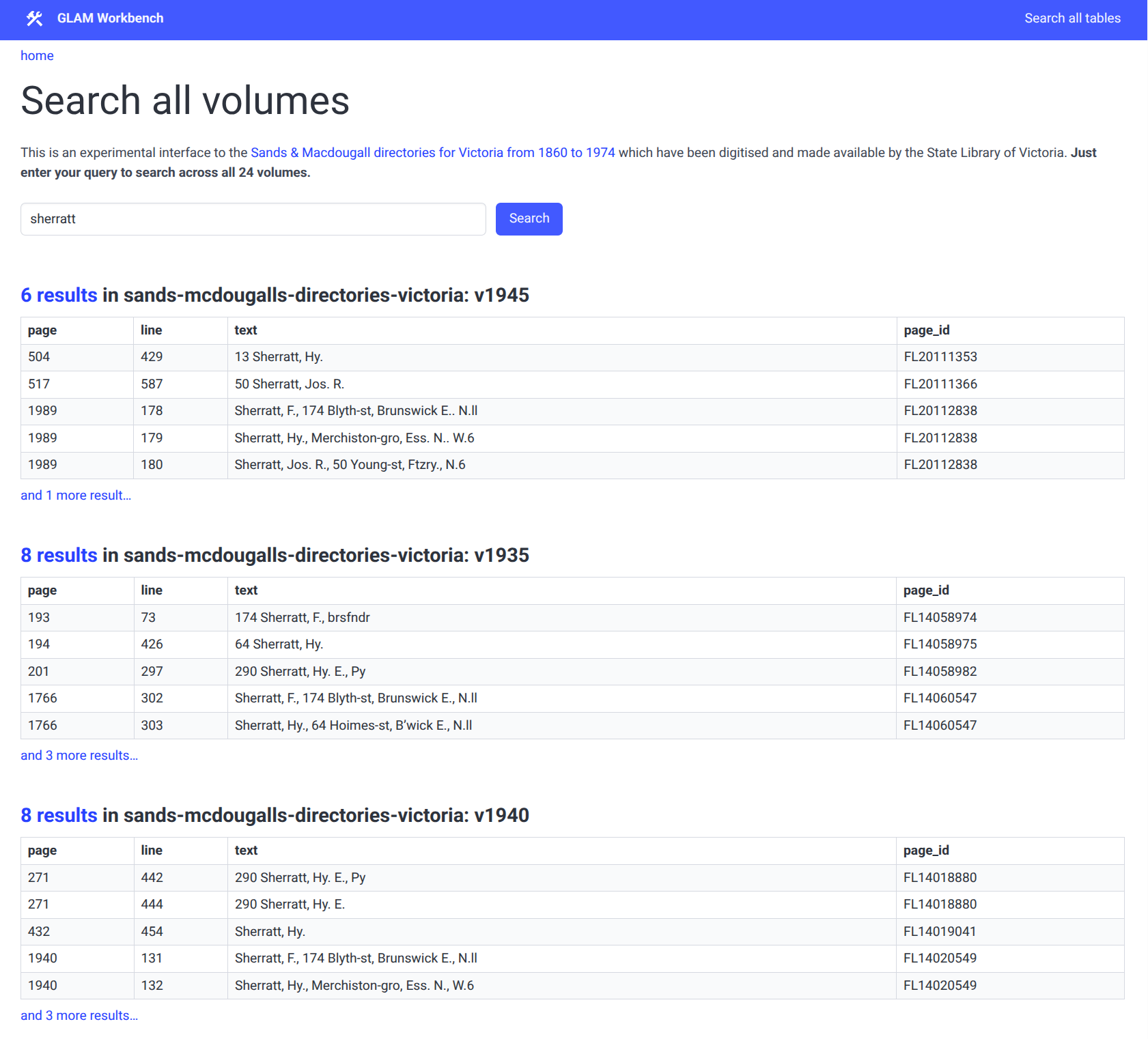

My new Sands & Mac database follows the pattern I’ve used previously to create fully-searchable versions of the NSW Post Office directories, Sydney telephone directories, and Tasmanian Post Office directories. Every line of text is saved to a database, so a single query searches for entries across all volumes. You can also use advanced search features like wildcards and boolean operators.

Search across all 24 volumes!

Search across all 24 volumes!

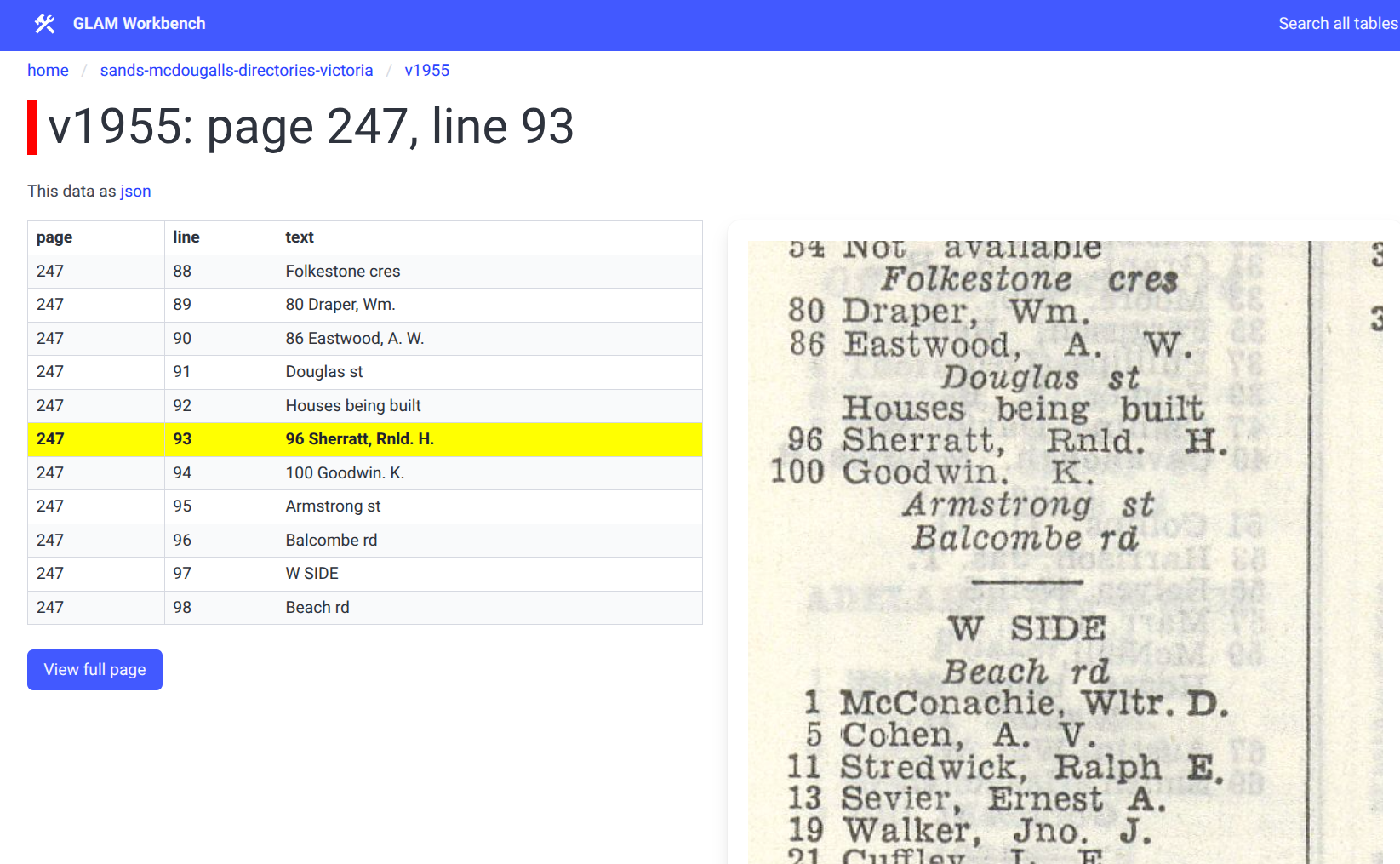

Once you’ve found a relevant entry you can view it in context, alongside a zoomable image of the page. You can even use Zotero to save individual entries to your own research database. This blog post from the Everyday Heritage project describes how the Tasmanian directories have been used to map Tasmania’s Chinese population.

View each entry in context! (Here’s my Dad building his first house in Beaumaris in the 1950s.)

View each entry in context! (Here’s my Dad building his first house in Beaumaris in the 1950s.)

There’s still a few things I’d like to try, such as making use of the table of contents information for each volume. I’d also like to create some additional entry points to take users directly to listings for individual suburbs (maybe even streets!). Each volume has a directory of suburbs, so it would be a matter of extracting and cleaning the data and linking the entries to digitised pages. Certainly possible, but I don’t think I’ll have time to get it all done before the end of my residency. Perhaps I’ll try to get at least one volume done to demonstrate how it might work, and the value it would add. As I was writing this blog post I also realised there’s a dataset of businesses extracted from the Sands & Mac, so I need to think about how I can use that as well!

Technical information follows…

I’ve documented the process I used to create fully-searchable versions of the Tasmanian and NSW directories in the GLAM Workbench. I followed a similar method for Sands and Mac, though with a few dead-ends and discoveries along the way.

Downloading the PDFs

I assumed that it would be easiest to work from the PDF versions of each volume, as I’d done for Tasmania. So I set about finding a way to download them all. There’s only 24 volumes, so I could have downloaded them manually, but where’s the fun in that?

I started with a CSV file listing the Sands & Mac volumes that I downloaded from the catalogue. This gave me the Alma identifiers for each volume. To download the PDFs I needed two more identifiers, the IE identifier assigned to each digitised item, and a file identifier that points to the PDF version of the item. The IE identifier can be extracted from the item’s MARC record, as I described in my post on exploring urls. The PDF file identifier was a bit more difficult to track down. The PDF links in the image viewer are generated dynamically, so the data had to be coming from somewhere. Eventually I found that the viewer loaded a JSON file with all sorts of useful metadata in it!

The url to download the JSON file is: https://viewerapi.slv.vic.gov.au/?entity=[IE identifier]&dc_arrays=1. In the summary section I found identifiers for small_pdf and master_pdf.

I could then use these identifiers to construct urls to download the PDFs themselves: https://rosetta.slv.vic.gov.au/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_func=stream&dps_pid=[PDF id]

Once I had the PDFs I used PyMuPDF to extract all the text and images. As I suspected the text wasn’t really fit for purpose. The OCR was ok, but the column structures were a mess. Because I wanted to index each entry individually, it was important to try and get the columns represented as accurately as possible. The images in the small PDFs were already bitonal, so I started feeding them to Tesseract to see if I could get better results. After a bit of tweaking, things were looking pretty good. But when I came to compile all the data, I realised there was a potential problem matching the PDF pages to the images available through IIIF. I found one case where some pages were missing from the PDF, and another couple where the page order was different.

As I was looking around for a solution, I realised that those JSON files I downloaded to get the PDF identifiers also included links to ALTO XML files that contain all the original OCR data (before it got mangled by the PDF formatting). There was one ALTO file for every page. Even better, the JSON linked the identifiers for the text and the image together – no more page mismatches!

Downloading the ALTO files

Let’s start this again shall we. After wasting several days futzing about with the PDFs, I decided to download all the ALTO files and extract the text from them. As I downloaded each XML file, I also grabbed the corresponding image identifier from the JSON and included both identifiers in the file name for safe keeping.

The ALTO files break the text down by block, line, and word. To extract the text, I just looped through every line, joining the words back together as a string, and writing the result to a new text file – one for each page.

It’s worth noting that the ALTO files include all the positional data generated by the OCR process, so you have the size and position of every word on every page. I just pulled out the text, but there are many more interesting things you could do…

Assembling and publishing the database

From here on everything pretty much followed the pattern of the NSW and Tasmanian directories. I looped through each volume, page, and line of text, adding the text and metadata to a SQLite database using sqlite_utils. I then indexed the text for full-text searching. At the same time I populated a metadata file with titles, urls, and few configuration details. The metadata file is used by Datasette to fill in parts of the interface.

I made some minor changes to the Datasette template I used for the other directories. In particular, I had to update the urls that loaded the IIIF images into the OpenSeadragon viewer. But it mostly just worked. It’s so nice to be able to reuse existing patterns!

Finally, I used Datasette’s publish command to push everything to Google Cloudrun. The final database contains details of more than 50,000 pages, and over 19 million lines of text! It weighs in at about 1.7gb. The Cloudrun service will ‘scale to zero’ when not in use. This saves some money and resources, but means it can take a little while to spin up. Once it’s loaded, it’s very fast. My original post on the Tasmanian directories included a little note on costs, if you’re interested.

More information

The notebooks I used are on GitHub:

- Download Sands and Mac PDFs and OCR text

- Load data from the Sands and Mac directories into an SQLite database (for use with Datasette)

Here are some posts about the NSW and Tasmanian directories:

- Making NSW Postal Directories (and other digitised directories) easier to search with the GLAM Workbench and Datasette (September 2022)

- From 48 PDFs to one searchable database – opening up the Tasmanian Post Office Directories with the GLAM Workbench (September 2022)

- Where’s 1920? Missing volume added to Tasmanian Post Office Directories! (September 2024)

- Six more volumes added to the searchable database of Tasmanian Post Office Directories! (November 2024)