Our 2025 Living Planet Report Canada (LPRC) used 5,099 population records for 910 species to track wildlife loss over time. But ecosystem health can’t be fully captured by a single knowledge system alone, so LPRC 2025 includes Indigenous perspectives from across the country.

Jared Davis, a member of Blueberry River First Nation in northeastern B.C., is the Cultural Protection Manager with his community’s Lands Department.

Jared Davis, a Cultural Protection Manager with his community of Blueberry River First Nation in northeastern B.C.

Jared Davis, a Cultural Protection Manager with his community of Blueberry River First Nation in northeastern B.C.

*After earning a degree in Native Stu…

Our 2025 Living Planet Report Canada (LPRC) used 5,099 population records for 910 species to track wildlife loss over time. But ecosystem health can’t be fully captured by a single knowledge system alone, so LPRC 2025 includes Indigenous perspectives from across the country.

Jared Davis, a member of Blueberry River First Nation in northeastern B.C., is the Cultural Protection Manager with his community’s Lands Department.

Jared Davis, a Cultural Protection Manager with his community of Blueberry River First Nation in northeastern B.C.

Jared Davis, a Cultural Protection Manager with his community of Blueberry River First Nation in northeastern B.C.

After earning a degree in Native Studies from the University of Alberta, he realized “there is only so much you can learn from a book and how important it is to reconnect with community and be on the land.” He moved back after he graduated.

Working as a cultural protection manager, he gained an understanding of the land and hunting and fishing regulations while engaging in geographical familiarization with the area’s wildlife and habitat.

Here’s what Davis told us on the changes he’s noticing in Blueberry River and the cumulative effects of development*:*

I started a community trapping subsidy program to help break down the financial barriers and get members back to hunting and trapping. My work as a cultural protection manager gets me connected on a deeper level with the people and to the land. I get to see reports on what they’re doing, what wildlife they see and all the pictures of the areas that really matter to them.

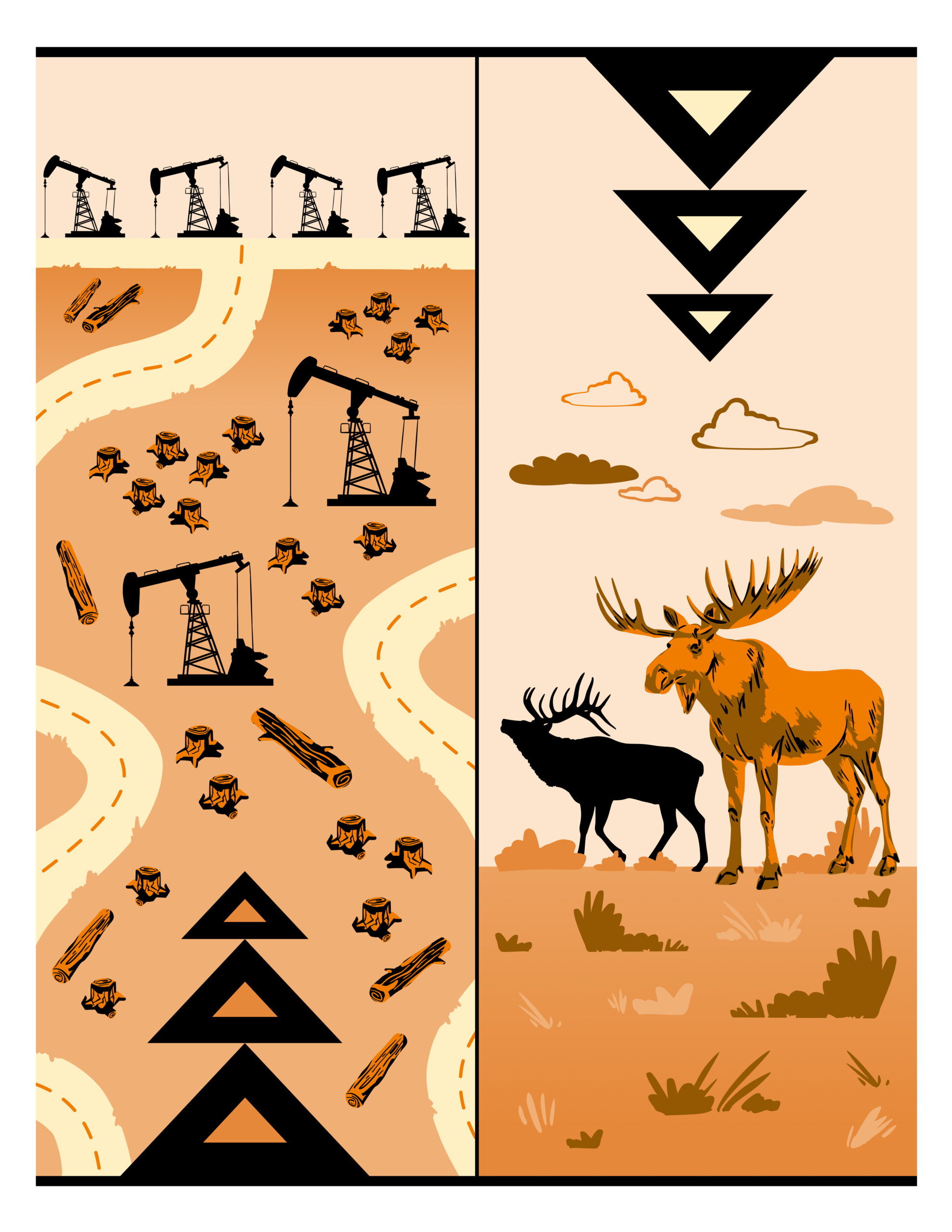

The amount of oil and gas, forestry and industry that’s taking place in the Fort St. John area (close to the border with Alberta), and the cumulative effects of it all has definitely affected our treaty rights to hunt, fish and trap.

It’s not just one threat

I talked to my Elders and my dad, and they said the moose and elk populations definitely declined from when they were younger. Before, you could walk out into trails nearby and you would find large bull moose and elk. They would be everywhere, and they would be much healthier than they are now.

Now, they are maintaining their populations but they are not growing, they are not thriving. The cumulative effects of more roads and development not only cause roadkill, but have changed their habitat and calving grounds, which affects their populations and how healthy they are.

Climate change is also a problem. This past winter was really bad. It didn’t get cold enough to kill all the ticks and a lot of the moose were covered. They were ghost moose that were either all white or had huge patches of missing hair because of the ticks.

Unfortunately, they don’t look healthy. They look skinny, and they don’t have a shiny coat. They don’t look appealing, and the meat isn’t as good.

Illustrated by Shawna Kiesman

Illustrated by Shawna Kiesman

Death by a thousand cuts

We recently won a huge court case against the Province. The British Columbia Supreme Court found that the cumulative effects of industrial development in our traditional territory have resulted in significant adverse impacts on the lands, waters, fish and wildlife. And that’s impacted how we can exercise our Treaty 8 rights.

Because of this, we created an implementation agreement with the Province. It outlines the cumulative effects on the wildlife populations that have declined, and how we can work together for land stewardship in the region.

Monitoring change together

Through the subsidy program, we make sure that our trappers and hunters are reporting any wildlife — taking pictures and detailing where they see it. They also note which roads are being used and what areas they’re in. We also have multiple wildlife camera projects underway to help us understand what animals are out there, and how many.

We would like to eventually develop more partnerships with the Province, possibly to do some collaring projects that will allow us to better understand wildlife movements and calving areas.

Wildlife are integral to us

The stability of wildlife is important to our people on multiple points. It is our connection to the land base that helps us ground ourselves and who we are as those people who have always hunted, trapped and fished on these traditional territories. That is a part of our stories and our connections.

Our Living Planet Report Canada 2025 reveals the most severe average wildlife population declines to date. Explore what’s happening in habitats across the country — and how we can halt and reverse wildlife loss before it’s too late.