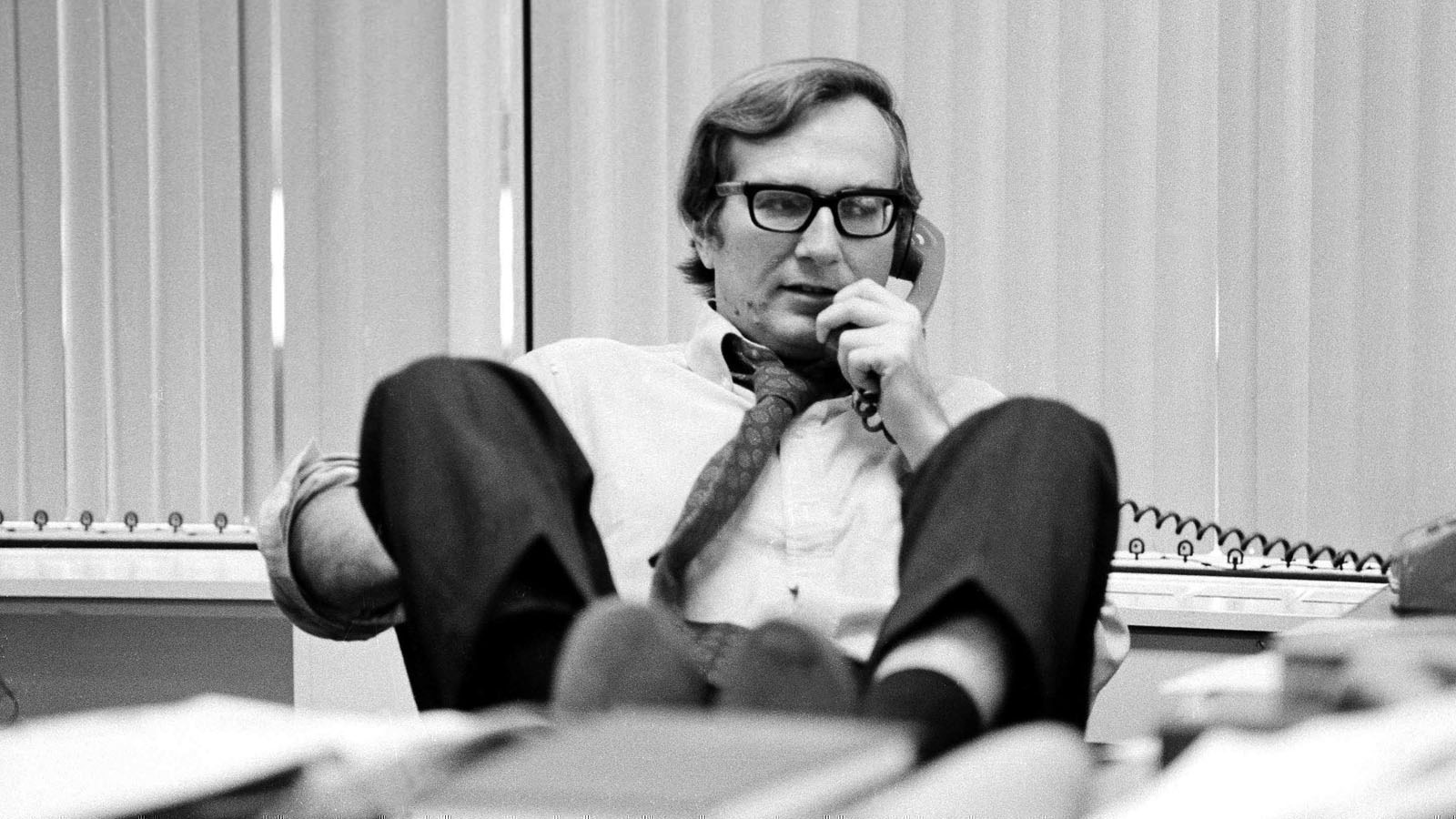

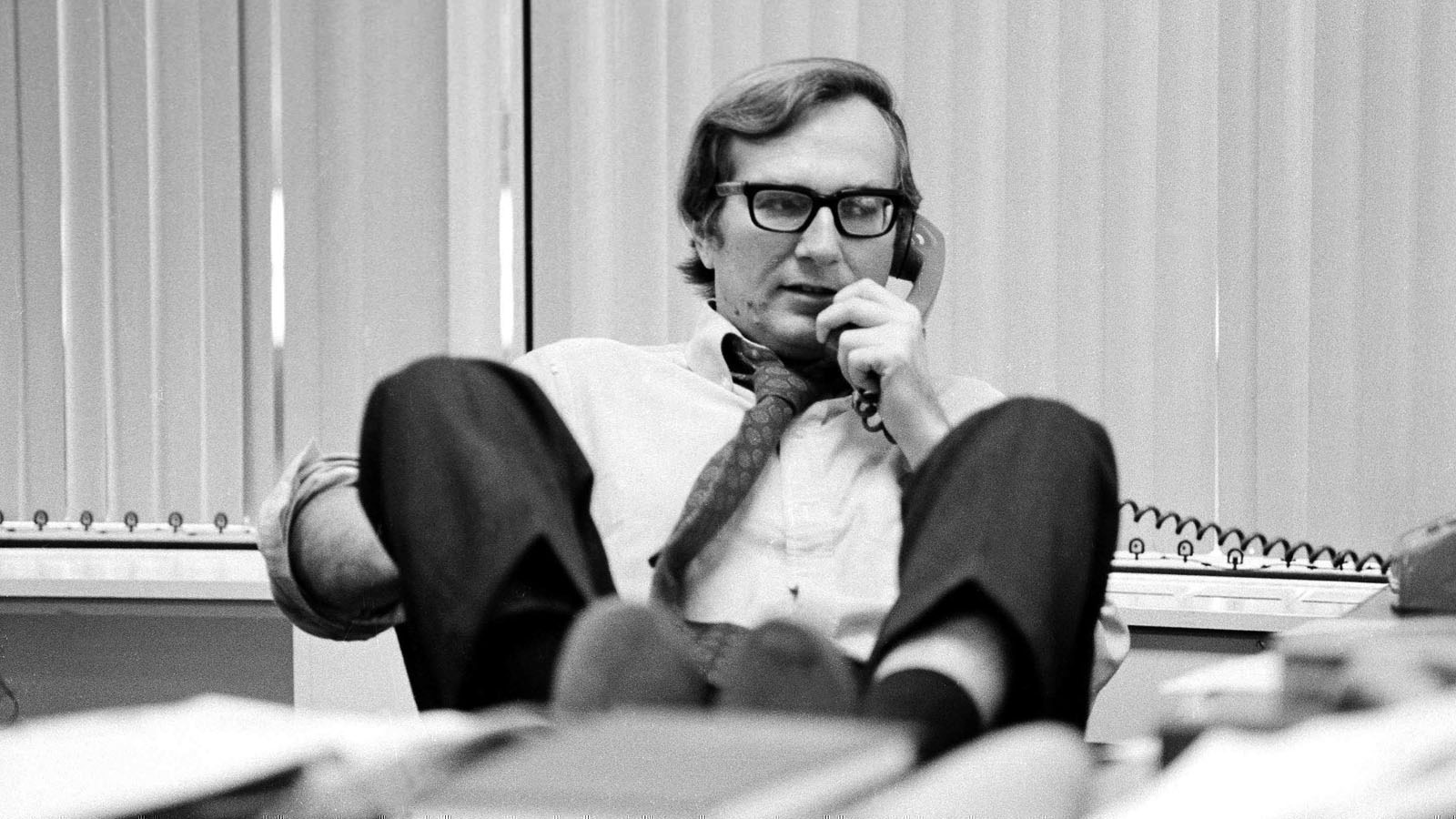

Seymour Hersh in Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Cover-Up (2025)

Of the four filmmakers with nonfiction features screening in the Main Slate of this year’s New York Film Festival, Gianfranco Rosi has been the most feted throughout the festival circuit over the years. Last month, his latest film, Below the Clouds, won a Special Jury Prize in Venice, where he won the Golden Lion in 2013 for Sacro GRA.

Seymour Hersh in Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Cover-Up (2025)

Of the four filmmakers with nonfiction features screening in the Main Slate of this year’s New York Film Festival, Gianfranco Rosi has been the most feted throughout the festival circuit over the years. Last month, his latest film, Below the Clouds, won a Special Jury Prize in Venice, where he won the Golden Lion in 2013 for Sacro GRA.

Below the Clouds

“For the most part,” writes Michael Sicinski at *In R…

Seymour Hersh in Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Cover-Up (2025)

Of the four filmmakers with nonfiction features screening in the Main Slate of this year’s New York Film Festival, Gianfranco Rosi has been the most feted throughout the festival circuit over the years. Last month, his latest film, Below the Clouds, won a Special Jury Prize in Venice, where he won the Golden Lion in 2013 for Sacro GRA.

Seymour Hersh in Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Cover-Up (2025)

Of the four filmmakers with nonfiction features screening in the Main Slate of this year’s New York Film Festival, Gianfranco Rosi has been the most feted throughout the festival circuit over the years. Last month, his latest film, Below the Clouds, won a Special Jury Prize in Venice, where he won the Golden Lion in 2013 for Sacro GRA.

Below the Clouds

“For the most part,” writes Michael Sicinski at In Review Online, “the documentaries that have made Gianfranco Rosi’s reputation have a firm basis in geography.” Sacro GRA “explored life in Rome as circumscribed by the city’s major beltway.” Fire at Sea (2016), the winner of the Golden Bear in Berlin, “considered the refugee crisis by focusing on life on the island of Lampedusa, a nexus of Italian and indeed European asylum immigration. Rosi left Italy to make Notturno (2020), a film about life along the borders of Iraq, Kurdistan, and Syria, an area plagued with the presence of Daesh terrorists. And now, with Below the Clouds, Rosi has made his most complex, most poetic film, based in and around Naples, a city that exists in the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius.”

“Shot in black and white, with sweeping landscapes so spectrally luminous as to resemble silver gelatin prints, Below the Clouds brims with gloomy beauty,” writes José Teodoro for Film Comment. “Behold plumes of cinders, colossal cones of Ukrainian grain, Japanese archeologists brushing dirt from bone, films projected in an empty cinema, archivists exploring vast rooms of fractured statuary with only a single flashlight.”

Writing for Documentary Magazine, Nicolas Rapold finds that Below the Clouds “bespeaks the fragility of civilization, as we keep seeing the remnants of empires past, with the Vesuvian burial of Pompeii connected to the present through today’s emergency calls about eruption tremors . . . But Below the Clouds is much less heavy or dry than that sentiment might sound, with a warmth and curiosity that lets scenes breathe, like watching two Syrian shipmates chatting in a tiny gym or hearing the study room’s bookish teacher guiding students along in their reading. And in one extraordinary moment, we hear an unexpected domestic violence emergency call that makes all the grand thoughts fall away before drama, eloquently puncturing any grand theorizing in the face of daily lived experience.”

BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions

Filmmaker, artist, and music video director Kahlil Joseph first launched BLKNWS as a multichannel installation at the 2019 Venice Biennale. Drawing from the Encyclopedia Africana—a compendium of studies of African and diasporic history and culture begun at the Library of Congress in 1871, expanded on by W. E. B. Du Bois, and eventually completed by Henry Louis Gates and K. Anthony Appiah—Joseph’s project evolved and traveled through museums and galleries before debuting as a feature, BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions, at Sundance in January. In her dispatch to Film Comment, Amy Taubin called it “by far the most exciting selection that I saw, in terms of both form and content.”

BLKNWS is “a kinetic blend of a fictional Afrofuturist narrative, archival research on decades of Black visual and multimedia work, and personal history,” writes Lovia Gyarkye in the Hollywood Reporter. “Joseph intersperses the story of a journalist reporting on a popular Transatlantic Biennale with footage of and excerpts from the work of Black artists like Senga Nengudi, Maren Hassinger, Garrett Bradley, Raven Jackson, Ja’Tovia Gary, and Alex Bell. The theories in BLKNWS are bolstered by Saidiya Hartman, Christina Sharpe, and Dionne Brand’s scholarship, and the film’s formal experiments are inspired by Jean-Luc Godard, Arthur Jafa, and Julie Dash. Joseph also uses BLKNWS to honor his late brother Noah Davis, a visual artist and cofounder of the Underground Museum in Los Angeles.”

“The challenge in this poetics is that any execution may, potentially, serve the concept equally well,” writes Mark Asch for the Art Newspaper. “Though BLKNWS now exists as a feature film, it’s more apt to call it a visual album—like Beyoncé’s Lemonade, of which Joseph was a key director. Its loose narrative, in which characters morph and recur like motifs, is plotted like a music video.” BLKNWS is “a film to wander in and out of, and at best embodies curator Okwui Enwezor’s description of art exhibitions as ‘thinking machines.’”

At IndieWire, Beandrea July finds BLKNWS “unconcerned with educating even as it doles out an endless stream of facts and corrections of erased histories. So for anyone who grew up steeped in the images of the film and made specific cultural memories associated with them, it soothes the nervous system [and] counters centuries of distorted messages about Black bodies in time and space adding up to a kind of psychic reassurance one didn’t know was possible.”

Cover-Up

Laura Poitras (Citizenfour, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed) has teamed up with fellow documentarian Mark Obenhaus on Cover-Up, a deep dive into the career of Seymour Hersh, the investigative journalist best known for exposing the truth behind the My Lai massacre. In 1968, U.S. Army soldiers murdered around four hundred unarmed civilians in the Vietnamese village of Sơn Mỹ, most of them women, children, and elderly men. The Army reported the deaths of 128 Viet Cong, and most media outlets simply passed that misinformation along—until, more than a year and a half later, Hersh broke the story through the Dispatch News Service.

“Cover-Up begins with Hersh recounting how that scoop came about,” writes Film Comment’s Devika Girish, “underlining that it didn’t require much in the way of hardcore detective skills: the facts were there in plain sight, but no one had taken the initiative to investigate or report them. This confrontation with passivity and complicity becomes a through line connecting the many stories—the litany of state-sanctioned crimes—that Poitras and Obenhaus have Hersh walk us through, including Operation CHAOS, the CIA’s secret program for spying on student protesters in the 1960s; the Watergate scandal; and the dark revelations of Abu Ghraib.”

IndieWire’s David Ehrlich finds that “in refracting more than fifty years of crime and conspiracy through the prism of Hersh’s career as an investigative reporter, Cover-Up is also the deepest and most damning film that Poitras has ever made about truth in America—and the power to control it . . . Pushing ninety but still as sharp and scraggly as ever, Hersh is a natural born yapper who’s always been drawn to the places where nobody wanted him to be (as his mother liked to put it), and he retains an encyclopedic memory of everything he discovered from such trespasses.”

Poitras spent twenty years pursuing Hersh until he finally allowed her to point a camera at him, and over that period, “some things have changed,” writes Sheri Linden in the Hollywood Reporter, “but the need for diligent muckrakers is as strong as it’s ever been. Hersh’s investigative reports no longer appear in the New Yorker or the New York Times; like many journalists who make it their business to question rather than transcribe the official story, he’s working independently, publishing on Substack.”

Landmarks

In 2009, Javier Chocobar, the leader of the Indigenous community of Chuschagasta in the northern Argentinian province of Tucumán, was murdered by a landowner and two former police officers who were trying to evict around three hundred Chuschagasta residents from their ancestral land. Lucrecia Martel followed the case, attended the 2018 trial, and with cowriter María Alché (Amalia in Martel’s The Holy Girl, 2004), worked for fifteen years on her first nonfiction feature. For Guy Lodge in Variety, Landmarks is a film of “steadily rising emotional impact and a long view of Latin American history that transcends any true-crime trappings.”

In a Notebook dispatch from Venice, Leonardo Goi noted that the “fraught dynamic between core and periphery—between haves and have-nots, between Argentina and Europe—has been a cornerstone of Martel’s cinema since La Ciénaga (2001), but the film’s visual language is a major departure. Landmarks opens in outer space, tracking satellites orbiting the planet, before protracted drone shots survey the mountainous landscape of Tucumán. This is a new camera movement for Martel, a prelude to a film that expands her vocabulary in radical ways.”

“Some may find the middle sections of the film, in which Chuschagasta community members are interviewed about their family histories, surprisingly straightforward for a filmmaker known for her audacious stylistic experimentation,” writes Devika Girish. “But this directness reinforces the impression I had of the film at large: that this is a movie invested in committing to the record lives that are frequently, purposefully erased. These scenes are a forceful counterpoint to the official proceedings, where documents, deeds, and laws serve as the means for a state to enforce its hegemony.”

At the A.V. Club, Natalia Keogan notes that when Martel returns to the case, “the resultant conclusion provides little catharsis. No matter how severe the penalty, no modicum of justice can be retroactively served when the struggle for self-preservation continues for this community and countless others. Yet even amid the indignation, perseverance prevails: Chocobar’s twenty-two-year-old nephew Alberto Catá, a key witness in the trial, traverses the country’s rugged hills, choosing a plot to construct a house for his future family—deeds and their owners be damned.”

Don’t miss out on your Daily briefing! Subscribe to the RSS feed.