Art as exploration and experience of space, body, and perceptions: since the 1950s, Lygia Clark (1920–1988) has pursued her practice by moving between the boundaries of painting, sculpture, and architecture. On display at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin until October 12 and then at the Kunsthaus Zürich from November 14 to March 8, 2026, her work offers a thoughtful look at the idea of shared space, the tension between form and movement, and art as a relational process rather than a specific object.

Lygia Clark. Retrospective, exhibitio…

Lygia Clark. Retrospective, exhibitio…

Art as exploration and experience of space, body, and perceptions: since the 1950s, Lygia Clark (1920–1988) has pursued her practice by moving between the boundaries of painting, sculpture, and architecture. On display at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin until October 12 and then at the Kunsthaus Zürich from November 14 to March 8, 2026, her work offers a thoughtful look at the idea of shared space, the tension between form and movement, and art as a relational process rather than a specific object.

Lygia Clark. Retrospective, exhibition view, Neue Nationalgalerie, 2025, © Neue Nationalgalerie - Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz / David von Becker

Lygia Clark. Retrospective, exhibition view, Neue Nationalgalerie, 2025, © Neue Nationalgalerie - Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz / David von Becker

Speaking at a conference at the Belo Horizonte School of Architecture in 1956, Lygia Clark proposed that the separation between disciplines should be overcome, suggesting close collaboration between the visual arts and architectural design, moving towards a spatial concept that was both architectural and pictorial. Her modular models sparked the interest of architects such as Oscar Niemeyer and Affonso Reidy, who considered them innovative contributions to modern design theories.

By the late 1950s, the Superfícies moduladas series had already transformed the geometric motifs of Clark’s paintings into modular and flexible three-dimensional systems, hypotheses of alternative living spaces that dialogued with modernist utopia and the social needs for adaptable housing. With the Neoconcrete Manifesto of 1959, and then with projects such as Construa você mesmo o seu espaço de viver (1960), Clark translated these ideas into concrete devices: spaces with movable walls and variable configurations, in which the inhabitant becomes a co-creator.

Lygia Clark, Superfície Modulada, 1955–1956, © Private collection

Lygia Clark, Superfície Modulada, 1955–1956, © Private collection

The series Estruturas de Caixa de Fósforos(1964) is a further evolution of this approach: matchboxes assembled into monochrome geometric constructions, which, thanks to this chromatic homogeneity, lose their identity as everyday objects, becoming elements that play with spatial rhythm, balance, and volumetric interaction. The work is no longer just visual abstraction, but a critical tool against the rigidity of official modernism. The idea here is a living, dynamic, and participatory architecture that anticipates the organic design and urban self-construction practices typical of Brazilian suburbs.

This retrospective—the first complete one dedicated to Clark in both Germany and Switzerland, and the largest in the world after the one at MoMA in New York in 2014 – is a unique opportunity to look back on the biographical and artistic career of one of the most radical artists of the 20th century, from her paintings of the 1940s to her Bichos (little animals) of the 1960s, and her performative and therapeutic works of the 1970s and 1980s. For Lygia Clark, construction, movement, and participation become tools for rethinking not only the language of art, but also the ways of inhabiting and experiencing space.

Beginnings and Neoconcretism

Born in Belo Horizonte in 1920 as Lygia Pimentel Lins, Clark embarked on her journey in Rio de Janeiro in the 1940s with architect Roberto Burle Marx and artist Zélia Salgado. Her artistic education began with painting, where she quickly transitioned from early figurative attempts to geometric abstraction and Concretism, before venturing into more experimental artistic territory. In 1950 she moved to Paris, where she studied with Fernand Léger, integrating some instances of the European avant-garde into her language. During these years he investigated the relationship between form and space, modulating surfaces, lines and colors to go beyond the limits of the traditional painting.

Lygia Clark, 1960er-Jahre, © Eduardo Clark

Lygia Clark, 1960er-Jahre, © Eduardo Clark

Back in Brazil, along with Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape, Amilcar de Castro and Ferreira Gullar, Lygia Clark became one of the central figures of Neoconcretism, a movement that emerged in the late 1950s as a reaction to the rationalism and scientific objectivity of concrete art of the São Paulo group. Clark moves away from strict geometric forms, instead emphasizing the significance of how participants engage with the artwork rather than its visual qualities, highlighting sensory interaction, direct involvement, and the poetic value of art. In Caminhando (1963), an unadorned paper strip in the form of a Möbius loop that individuals trim along perpetual trajectories, Clark foregoes her authorship: the piece is no longer a finalized product, but rather an expansive action, which can be repeated and modified by anyone. It is at this point that she matures the notion of “proposition,” a term by which she will define her works: invitations to experience, sensory devices, rather than works to be contemplated.

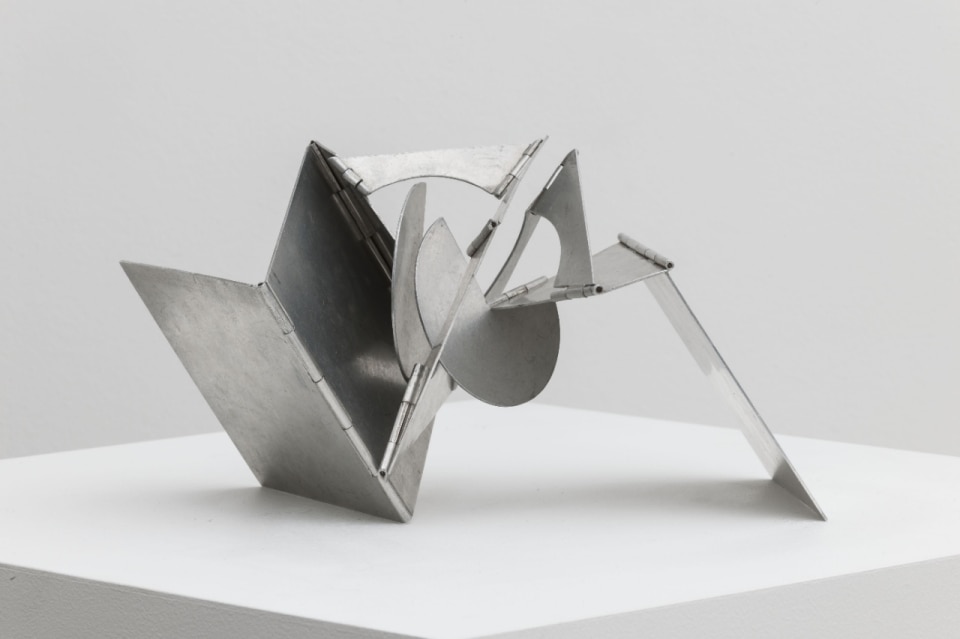

Lygia Clark, Bicho De Bolso, 1966, © Private Collection

Lygia Clark, Bicho De Bolso, 1966, © Private Collection

The next step comes with the Bichos, articulated metal sculptures that invite manipulation and interaction. These aluminum “critters,” made beginning in the mid-1960s, represent the most radical response to the problem of sculpture as an autonomous object. In Clark’s view, showcasing them sealed in glass cases is senseless because they are active organisms that animate only when a participant engages with them. At the Neue Nationalgalerie there are authorized replicas of them accessible to the public, which can be activated by visitors, bending them and changing their form. Their silver surfaces open and close in ever-changing forms, challenging the distinction between sculpture and painting, between stability and transformation. In the Bichos the neoconcrete vision is condensed: to go beyond the object, to return primacy to experience, and to reaffirm the body as a generator of meaning.

Paris and the architectures of the body

1968 marks a decisive moment for Lygia Clark, who that year participates in the Venice Biennale and moves to Paris, where she will remain in exile until 1974, due to the military dictatorship in her country. Here she expands her propositions into collective experiences, which she calls Arquiteturas biológicas. With poor materials – plastics, rubber bands, nets – she builds ephemeral spaces, tunnels, cocoons in which the bodies of the participants become part of the work itself.

Lygia Clark, Biological Architecture nº2, 1968, © Cultural Association “The World of Lygia Clark”

Lygia Clark, Biological Architecture nº2, 1968, © Cultural Association “The World of Lygia Clark”

Works such as O eu and o tu (1967) or Ovo-mortalha evoke birth and death, protection and constraint, creating organic structures where the individual is a cell of a collective body. In these works the phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty resonates, for whom the body is not one object among others in the world, but is the “flesh” itself of the world and the condition of experience that makes its perception possible. When in 1972 she was invited by the Sorbonne to teach a course on gestural communication, Clark had the opportunity to explore more deeply with her group of students the ideas of some earlier performance works, such as Baba antropofágica and Canibalism, both first formalized in 1969. Saliva-soaked threads entwined around a lying body, or fruit eaten by participants blindfolded on a human belly, the performances re-enacted with the collaboration of her students embrace the enigmatic nature of the body, in an action that becomes almost a ritual with no external audience, and where the participants themselves are constructors of meaning through dialogue and sharing. The experience requires total involvement, not only culturally and socially but also bodily, biologically, with the aim of bringing to life what Clark calls a “collective body.”

In her letters to her friend Hélio Oiticica Clark speaks of “becoming an authentic bicho,” of experiences that unhinge the ego to reveal primal desires and fears. These are not voyeuristic spectacles: the body is both an artistic medium and a terrain of political resistance, an indirect response to the violence of the Brazilian dictatorship that Clark, from exile, observed with anguish.

From participation to therapy

In the 1970s Lygia Clark’s research took a decisive turn toward the intimate dimension of therapy. Inspired also by Donald Winnicott’s theories on transitional objects, the artist develops her Objetos Relacionais: shells, stones, water-filled pantyhose, bags, gloves stuffed with materials of the most varied consistencies. Everyday objects that, in the hands of the artist, become instruments of transformation. Used during sessions with psychiatric patients, these devices aimed at reconstructing a fragmented body image, awakening forgotten sensory memories, restoring trust through the immediate and primary language of touch.

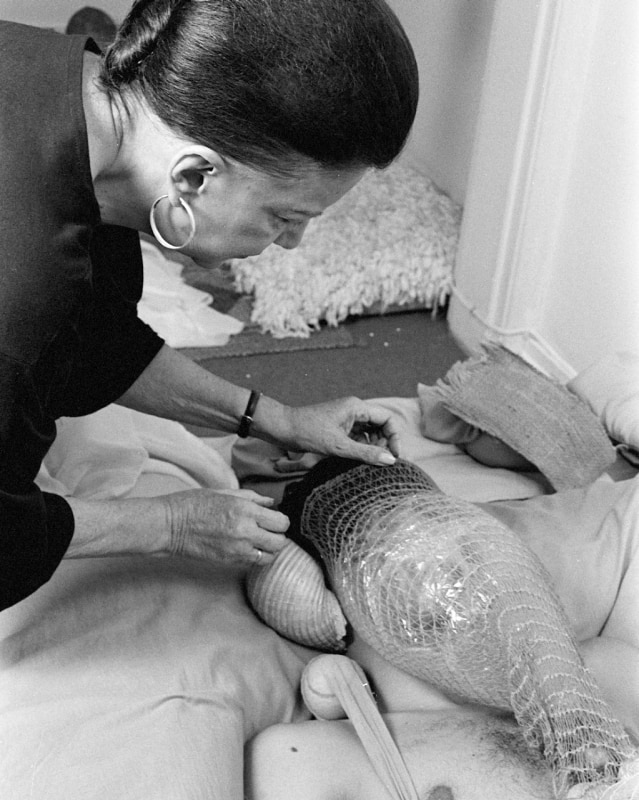

Lygia Clark, Collective Body, 1970, © Cultural Association “The World of Lygia Clark”

Lygia Clark, Collective Body, 1970, © Cultural Association “The World of Lygia Clark”

The experience for Clark is never aesthetic in the traditional sense, but deeply relational: the work does not exist except in the encounter between the object, the body and the psyche of the participant. The documentary Body Memory (1984), by director Mario Carneiro, focuses on sessions of “Structuring the Self”, the art therapy method conceived by Lygia Clark and to which she devoted the last years of her life, after turning her back on the art market. In these practices, the artistic gesture is transformed into a healing gesture, and the aesthetic relationship becomes an experience of mutual trust, recomposition, and symbolic healing. As the artist herself says in the early 1960s, art aims to combat depersonalization and to give modern man a chance to know himself. A possibility that Lygia Clark through her works offers especially to those who participate, even before herself.

Lygia Clark, Strukturierung des Selbst, 1976, © Cultural Association The World of Lygia Clark

Lygia Clark, Strukturierung des Selbst, 1976, © Cultural Association The World of Lygia Clark

Opening image: Lygia Clark, Estruturas de Caixa de Fósforos, 1964, Gouache paint, matchboxes, © O Mundo de Lygia Clark-Associação Cultural, Rio de Janeiro; photo: Michael Brzezinski, Private Collection, London; Courtesy Alison Jacques