Rocketwerkz CEO Dean Hall and Floating Point Origin Interactive founder Felipe Falanghe sound downright giddy when they talk about the new C# framework named “Brutal.” During a recent call with Game Developer, the brains behind DayZ and Kerbal Space Program couldn’t stop making random asides to each other about what they’ve pulled off with the tool and how they’ve inspired each other’s work.

Their joy was infectious because once you understand how Brutal functions, you realize every new feature is a bona fide accomplishment even for this pair of seasoned developers. “It’s called Brutal for a reason,” Hall said after Felipe compared working with it to the experience of sitting on a bar stool while all your friends using engines like Godot are sitting on a co…

Rocketwerkz CEO Dean Hall and Floating Point Origin Interactive founder Felipe Falanghe sound downright giddy when they talk about the new C# framework named “Brutal.” During a recent call with Game Developer, the brains behind DayZ and Kerbal Space Program couldn’t stop making random asides to each other about what they’ve pulled off with the tool and how they’ve inspired each other’s work.

Their joy was infectious because once you understand how Brutal functions, you realize every new feature is a bona fide accomplishment even for this pair of seasoned developers. “It’s called Brutal for a reason,” Hall said after Felipe compared working with it to the experience of sitting on a bar stool while all your friends using engines like Godot are sitting on a comfy couch.

Brutal is, to quote a Rocketwerkz spokesperson, a tool that “uses the latest .NET features while providing low-level API access to high-performance C++ libraries and tools, including a Vulkan graphics API.” That’s it. That’s all you get.

Rocketwerkz created the framework to develop Kitten Space Agency, a spiritual successor to Kerbal Space Program. The company invited Falanghe onto a steering committee consulting on Kitten Space Agency, which has led to him consulting him on the engine. Brutal will be made open source through a commercial entity called “Ahwoo.”

Related:Unity unveils new toolkit to accelerate multi-platform launches

Developers who remember the days of XNA and home-brewed engines may shudder at the prospect. Visual scripting tools like Unity and Unreal Engine were supposed to speed up development and let designers think more about their game and less about blocks of code. Why would we go back to a world where everyone’s building their own game engines?

Hall understands that nervousness. But in our conversation he made a rather bold prediction: frameworks like Brutal, not game engines, will be the future of the game development.

Brutal forces developers to build workflows from the ground up

To follow Hall’s thinking, you need to think about Brutal in terms of developer workflows, not what it can or can’t do compared to third-party game engines.

Rocketwerkz created Brutal to drive development of Kitten Space Agency, but that’s because they determined scene-based rendering wasn’t sufficient for the task. “If you take Unity or Unreal, you have this editor scene and push play, it becomes a game scene and everything in it is relative to 0-0-0 of that scene,” said Hall. “That’s how you draw things, and it’s so ingrained that people have a hard time imagining something that’s different.”

Related:Obituary: Interplay co-founder Rebecca Heineman has passed away at 62

“In Kitten Space Agency, everything’s contextual. So an object is drawn relative to something else. The camera is actually always at it’s 0-0, it never moves, and everything is drawn into it.”

Spaceflight simulators depict long distances, a concept in rendering sometimes called “floating origin.” Falanghe said he was rethinking his approach to this in his new project and came up with a similar solution to Rocketwerkz, calling it “first-order floating origin,” where the system resolves the positions of objects to be relative to the camera as late as possible before rendering. “You still get the basically the same functionality, but you get to use high precision numbers as far as you can into the game execution,” he explained.

“In our case, we resolve them on the GPU. We send a pair of of numbers that act like a double precision value to the shaders, and the shaders then figure out the camera relative coordinates.” To do anything similar in Unity (the tool Falanghe used to make Kerbal Space Program), you have to “brute force” the existing system by telling it to shift every object in the game world by the same amount.

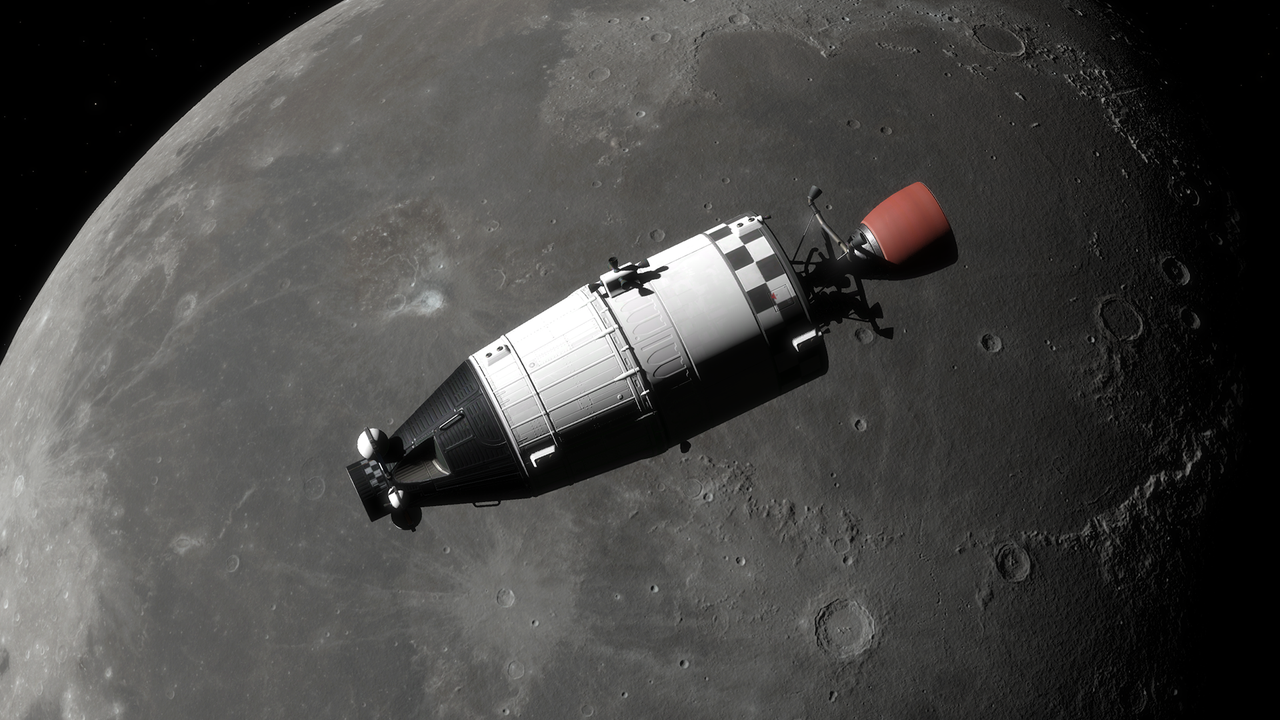

Image via Rocketwerkz

For developers wondering about optimization performance in Brutal—Rocketwerkz explained that Kitten Space Agency’s C# code runs on the Common Language Runtime (CLR) and is JIT-compiled when the game runs instead of being compiled native ahead of time. This was done in part to make the game “easier to mod,” since the managed code is “more accessible” to players.

Related:Spooky MMORPG networking stories from Guild Wars and Guild Wars 2 - GDC Podcast Ep. 56

Pay attention to the process though. The thinking wasn’t “Unity can’t do this, I need a tool that can do this.” It was “our game needs floating origin to work this way, how do we do it?”

It’s a mindset that comes naturally to Falanghe, Hall said. “One of [Falanghe]’s superpowers that I don’t think he quite realizes he has is he’s always thinking about how he wants to do something, especially if it’s not something that he’s super familiar with.”

In a second call, Hall showed us other Kitten Space Agency systems built through Brutal. Some, including one that used volumetric lighting to create engine glow went a bit over my head, but Hall’s system for mathematical-based user interface features was easy to understand.

Kitten Space Agency lets players simulate space flight with a number of semi-realistic UI elements that can be expanded or shrunk and even moved to other monitors. Video game UI is usually texture-based, but Hall wanted these to be math-based to allow for that scaling and repositioning. He also feels these look crisper and less “washed-out.”

These are among a number of Kitten Space Agency systems that are technically possible in other game engines, but by building them from the ground up, developers can answer the question “what am I trying to do?” before they ask “how am I trying to do it?”

Hall and Falanghe said this was made possible by a very coincidental series of events that happened alongside the making of Brutal: the advancement and popularization of large language models in generative AI.

Brutal workflows are the opposite of vibe-coding

“It’s hard for me to talk about it without sounding like a cult member,” Hall said sheepishly, when describing how he uses ChatGPT while working in Brutal. But he and Falanghe agreed—using LLMs has made language-based coding an easier task.

Not that much easier, to be clear. They both said that when querying an LLM, they rarely copy and paste whatever code it generates. Instead they ask questions about C# libraries or Vulkan documentation, and the software is able to return high-quality answers. Answers that normally require programmers to sit down for hours to pore over documentation or scour ancient forums to find that one post with the solution (which was probably written in 2014).

“An LLM is essentially tokenizing language, then putting masses of vectors around that to build linkages between those tokens,” said Hall. “What could be better than a highly-structured, in fact brutally structured language?” Vulkan and the latest version of C# are very “highly structured, with very clear syntax.”

Developers critical of ChatGPT maker OpenAI should be able to replicate this process on open source models like DeepSeek, Falanghe said (though he hasn’t tried this himself).

This process doesn’t work as well with Unity and Unreal because they’re both “highly spatial” as a result of their visual scripting tools. A solution for one game’s problem may not work with another because of the different scripted elements. LLMs scouring the web can’t produce consistent answers.

It is also the opposite of vibe coding, a method where programmers tell an LLM what they want a system to do and it generates code—and it isn’t code completion, where AI tools “predict” what someone is typing and finish the string for them to speed up their workflow. The only thing the LLM does for Brutal developers is speed up access to information, letting them research without watching a 40 minute YouTube video.

Falanghe said he even tried “vibe coding” at one point with ChatGPT but found it inadequate. He compared the experience to being “a project manager who’s not a coder” and badly communicating with a programmer about how to make an application. They’ll give you something that’s almost correct, but not quite what you wanted, and you’ll just go back and forth iterating and making it worse and worse.

“You don’t need to pay somebody to have that experience, you can just do it with an AI and be frustrated,” he quipped.

How can frameworks change game development?

You can boil down Hall’s theory about what he calls “the death of big engines” to this: if LLMs make language-based coding more accessible, than visual-based scripting loses its edge. Developers who embrace the Brutal method become responsible for understanding every piece of tech powering their game.

It’s a difficult task, but one that doesn’t require them to understand the parts of their tools that don’t go into their game.

And despite the difficulty of using the framework, Hall said Rocketwerkz has had an easier time recruiting programmers using this tool than they did using Unreal. High-level Unreal programming requires highly specialized knowledge tuned not just for the engine, but the kinds of games being made. A programmer already familiar with C# can pick up the Brutal workflow if they’re willing to embrace its... well, brutality.

Hall brushed off the notion that Brutal would be the sole framework driving an end-to-game engines. He even grew a tad prickly at the notion that some companies might establish themselves as Brutal experts who can build tools for other developers on top of the framework, akin to developers making plugins for Unity and Unreal. “Brutal was made to deliver a very specific, kind of hard-to-make game where you need to sit down and ask a whole bunch of questions [about how it works].”

“I don’t like the idea that Brutal would then become this one-size-fits-all pocket knife because I don’t think that’s true. In my heart of hearts, I think someone else might create something else that follows a similar approach, but simpler.”

Hall’s vision of the future game industry is almost the polar opposite of the one pitched by UGC platforms and AI boosters. Instead of a world where game development becomes easier through simplified tools, it becomes more accessible through easier understanding of language-based programming through LLMs.

Skeptics could brush this off by saying language-based coding could never move as fast as engine-based game development. If that were true, the Kitten Space Program alpha would have taken years to produce, right?

Hall addressed this point while flying through his team’s simulated solar system, careening through the canyons of Mars quickly after directing a craft to initiate a landing on the detailed surface of Earth’s moon. “We made all of this in about a year,” he said.

About the Author

Senior Editor, GameDeveloper.com

Bryant Francis is a writer, journalist, and narrative designer based in Boston, MA. He currently writes for Game Developer, a leading B2B publication for the video game industry. His credits include Proxy Studios’ upcoming 4X strategy game Zephon and Amplitude Studio’s 2017 game Endless Space 2.