At the opening of the new French series La vraie vie, we are introduced via video chat to working actor Victor Assié with directors off-sc. “We have a role for you,” they say. “But not in real life.”

Assié puts his hands on his head, quizically, trying to comprehend. “I don’t understand,” he says. And in an instant, we are somewhere else. Assié has transformed into a virtual version of himself, and we’re sitting alongside him as he is shuttled to the coast of an idyllic French island town. He passes a police station, a man staring at the water, a gyro stand, and a taxi blasting music from the dock. Like Assié, these are all real people populating the island’s activities. “We’ll be with you, but not in-game,” Barbier and Cauisse tell Assié, shortly before making landfall. “Get …

At the opening of the new French series La vraie vie, we are introduced via video chat to working actor Victor Assié with directors off-sc. “We have a role for you,” they say. “But not in real life.”

Assié puts his hands on his head, quizically, trying to comprehend. “I don’t understand,” he says. And in an instant, we are somewhere else. Assié has transformed into a virtual version of himself, and we’re sitting alongside him as he is shuttled to the coast of an idyllic French island town. He passes a police station, a man staring at the water, a gyro stand, and a taxi blasting music from the dock. Like Assié, these are all real people populating the island’s activities. “We’ll be with you, but not in-game,” Barbier and Cauisse tell Assié, shortly before making landfall. “Get your license, buy a car,” but you’re on your own.”

And so are we.

Assié has been haplessly thrust into a “roleplay” server built on the popular military shooter Arma 3. Role-play servers operate exactly as they sound–rather than taking on the fictional narratives provided by a game’s creator, role-play games are a simulacra, real people playing fake roles in a real way. The five-part TV series on ARTE France follows Assié from his early unsuccessful attempts at building a life, from acting to driving a bus, before finding his true calling: a documentarian of the lives of the people he encounters.

Much like Nathan Fielder’s *The Rehearsal *or Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-up, *In Real Life *plays with the meta-concept of its title but in the context of a video game environment. The material is rife with contradiction. They are documentarians filming a documentary about making a documentary in a virtual world. While we can see the digital character’s lips moving in a close-up, Barbier and Causse were brutally aware of the intimate strangeness of that person being near and far away simultaneously. “He’s out of frame and in frame at the same time,” Barbier explained to me, likening Assié’s “performance” to a type of digital puppetry. “It’s a new way to see characters through a film.”

“It’s this prism when you’re looking at things where everything is simplified, and at the same time very complex, you know?” Causse says about filming in games. “It’s just representations of things. What values are you putting into those realities?”

Documentary Without Judgment

Barbier, Causse, and fellow filmmaker Quentin L’Helgouac’h met each other in film school and started talking about games as the open-ended sandbox genre began to take off in the 2010s, like Rust, and Minecraft. These are online games, definitionally connected to the development of the social web, and unlike other narrative games, the absence of story allowed emergent narrative to blossom.

Barbier and Causse were immediately drawn to the question of these games’ appeal. “It’s this basic documentary question that you ask to someone to understand,” Causse said. “Why are people playing this game?” After an initial short film in *Grand Theft Auto V, *they spent six years and over 900 hours developing Knit’s Island, a documentary on staying alive in the zombie survival game *DayZ. *“It’s a medium, not a subject for us,” Barbier said.

There is a tendency for writers or filmmakers stepping into games to over-explain their environment, as there is a fear that audiences will be lost along the way. Consider The New Yorker’s 2010 survey of the year’s popular games, where Nicholson Baker approached games with a deliberate naïveté. He shared his stunning observations that video games were long and video games were challenging before closing his missive with “I miss grass.” (To my knowledge, he has not written about games since then.) Work for a “general” audience about games usually struggles to balance explanation with a presumption of visual literacy.

Refeshingly, Barbier and Causse peddle almost none of these cloying, mandatory pleasantries about what the film is. They don’t provide a history of role-play servers. There are no talking heads. They recorded a voice-over early on, but abandoned it, instead relying on Assié’s in-game conversations with everyone around him. “It’s pretty boring to try to explain that you are in a roleplay server,” Barbier joked. “Do I want to spend 20 minutes telling someone that you are in a game?” Instead, Assié’s unfamiliarity is a comic foil as he flits between the grind (getting a driver’s license) and the profound (reflecting on the difficulties of a life in the arts).

The series is so dogged about maintaining a presence in-game that I succumbed to the illusion that this was, in fact, a documentary…in real life. Assié and a new friend Emiliano, share the beauty and wonder of a sunset flight, and we sit in the backseat, watching a new friendship emerge. The two continue to talk through the night, scouting a location for an in-game project, and Emiliano offers an in-game therapy session (as he’s a psychoanalyst IRL). “We wanted to get close to that feeling that we don’t know what’s real anymore or what the film is about,” Barbier said. “

This fly-on-the-wall approach delivers a genuine, unfiltered, and unique look at how the online community conducts its lives. “The ‘direct cinema’ approach was not something you see in games,” producer Boris Garavini told me, referring to the mid-century documentary movement that pared down cameras and crews to capture the essence of their subjects. Working with editor Nicolas Bancilhon, who had never played games, gave the work “a fresh eye,” Garavani continued.

There’s a perception in game-based films that one can simply do whatever you want are unrestrained by the real work. However, the team took the opposite approach to get the look they wanted, maintaining purity by using Arma’s camera without embellishment. Part of the series’ allure is the mix of the shakes of L’Helgouac’h’s camera juxtaposed with long-distance takes of the island’s scenery. “Sometimes we used the camera as a fake object,” Barbier said about their efforts to pull natural performances out of their amateur subjects. “We wanted to let people know that something is happening, but we wanted to provoke some situations.”

However, more practical concerns, familiar to documentarians who shoot in dangerous environments, quickly emerged. Shoots were long, often eight hours or more, and players frequently moved too fast to capture in frame. If someone were hurt on-set, they’d have to wait for an ambulance to amble to their location. But then they would also have to continue the requisite role-play with the firefighters, transforming a minor hiccup into an hour-long snafu. “Every shot is kind of a success, you know?” Barbier said.

Islands, Cops, and the Tedium of Small-Town Life

Islands, in particular, can be really strange places. The ports guarantee that you always know who’s coming and who’s going. People are there, and they never leave. And on a digital island, buffeted from the eroding effects of time, the island never really changes. The safety that the island preserves brings its inhabitants comfort and solace.

Barbier compared the town to Frederick Wiseman’s 2019 film Monrovia, Indiana, which takes a microscopic view of the town’s 2,000-person population and follows everything from debates about fire hydrant location to travails of a collision repair shop. “It’s a type of monoculture,” Barbier said about both the tiny American town and the virtual world of the same size. At one point, Barbier came across a couple of players who were rebuilding a wall with small stones, because passing cars had slowly chipped away at the structure. “They were just like building and rebuilding the walls,” Barbier said. “I was like God, it’s a part of the setup and they’re just rebuilding it over and over again.”

The tedium of small-town life is on display in other ways. First, the setting is surprisingly unambitious. It is the year 2030. Emmanuel Macron is president, for some reason. Second, there is a chit-chat everywhere as players in character make up dead air with standard fare about the weather and local gossip. Finally, there is a stunning amount of paperwork and administration: license plates, registrations, staffing agencies, and insurance.

Perhaps nothing marks the indignities of a small town more than the cops. There are simply cops everywhere. They pull over Assié for running a red light, for not wearing a helmet, for performing a play without a permit, for honking too aggressively, for illegal parking. No specific laws are ever referenced (they’ll sure get around to it), but the police offer vague, and often menacing, accusations of general disorder. Perhaps the omnipresence of a police state is too be expected in a game built on the bones of a military shooter. But the social masks of *playing *cops is sufficient to turn people into a hackneyed version of cops pulled from film and tv. “People are trying to be their best version of a policemen or firefighter while acting, which is the worse thing to do,” Causse said. So, basically, assholes.

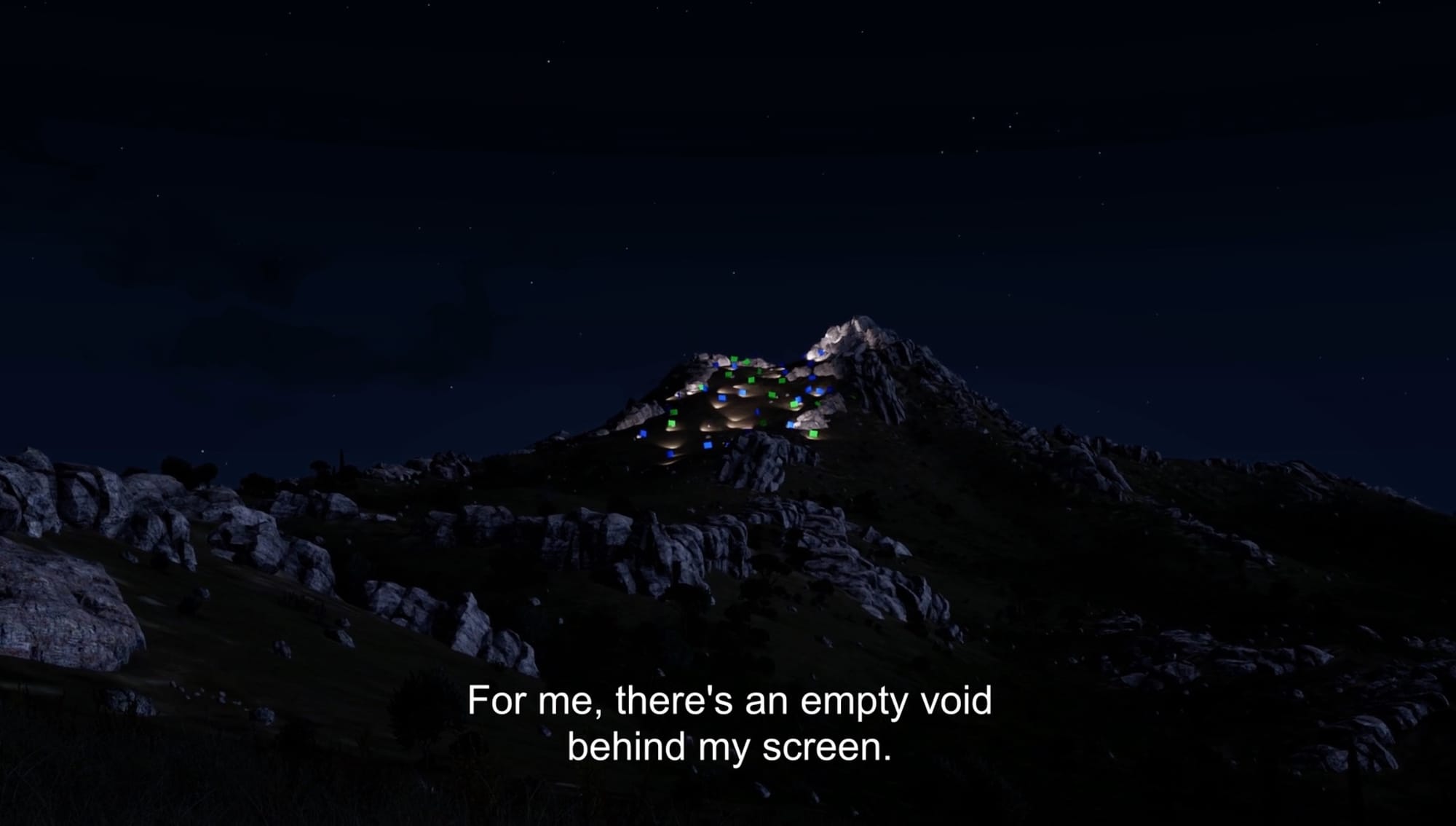

At the same time, there aren’t enough cops to actively manage the island directly. Thankfully, an active culture of snitching alive and well leaves no discretion undocumented. During one sequence, they arranged a serene long-shot of dozens of blue and green screens on a rolling set of hills. But inevitably, someone would call the police, who would destroy all of their equipment (as cops are wont to do).* *Philosopher Immanuel Kant once observed, “The nice thing about living in a small town is that when you don’t know what you’re doing, someone else does.”

When Friendships Only Exist in Virtual Space

The relationship between the open-ended nature of role-play and a small town’s naturally oppressive dynamics was often in tension. On the one hand, it’s—surprise, surprise—a video game. Nothing matters in the liberating way that games free us from the strictures of our actual lives. On the other hand, it is a game populated by people who bring their own wants and needs to bear on the virtual world around them.

In fact, it’s the quotidian concerns that breathe life into the film. It’s rarely grand conversations about life and death, but the daily interactions between Assié and his newfound compatriots that give the film a real sense of place. There are so few people there daily, that friendships and romances are almost inevitable. Barbier said that they wanted Assié to make friends, but couldn’t force a fraternity (it’s mostly men on the island). More importantly, a video game stripped of its global concerns can focus players on each other, instead of Arma 3’s* *imagined regional conflicts.

Thankfully, Assié builds a natural rapport with the aforementioned Emiliano and the two spend more and more free time together. Emiliano shuttles Assié around and gives him tips on how to find a job. The friendship symbolizes Assié’s relationship to this place, which has become a home of sorts. He is on the precipice of moving from a tourist to a local. “The main question for Victor was just do you really want to be here?” Causse said. As you feel the series winding down and Assié’s filming comes to a close, they discuss perhaps meeting each other in real life. But they don’t do it.

“With some friendships once you get of its context, it can break up everything,” Barbier says. “When you meet the real person, the character dies.”