A team of Hungarian archaeologists believes they have located the place where Emperor Valentinian I suffered the stroke that cost him his life in AD 375, on the Danube frontier.

In the cold autumn of AD 375, the Roman Emperor Valentinian I, known for his fierce temper and firmness in defending the frontiers, was in the legionary fortress of Brigetio, in the province of Pannonia (modern-day Hungary). His mission was to punish the barbarian tribes of the Quadi and the Sarmatians, who a year earlier had devastated the region. On November 17, he received an embassy of Quadi who came to negoti…

A team of Hungarian archaeologists believes they have located the place where Emperor Valentinian I suffered the stroke that cost him his life in AD 375, on the Danube frontier.

In the cold autumn of AD 375, the Roman Emperor Valentinian I, known for his fierce temper and firmness in defending the frontiers, was in the legionary fortress of Brigetio, in the province of Pannonia (modern-day Hungary). His mission was to punish the barbarian tribes of the Quadi and the Sarmatians, who a year earlier had devastated the region. On November 17, he received an embassy of Quadi who came to negotiate. According to the chronicles, the excuses of the envoys and their attempt to blame Rome for the war so enraged the emperor that, in a fit of anger, he suffered a stroke and died.

For centuries, the story of his death has been known through the writings of the historian Ammianus Marcellinus. However, the exact location within the vast fort of Brigetio where this crucial event took place had remained in complete obscurity. Until now.

A multidisciplinary archaeological investigation, the results of which are now being published, has brought to light the remains of an impressive building with an apse at the heart of the fortress. The researchers propose that this space, built specifically for representation and reception purposes, is the most likely candidate to have been the setting of that fateful encounter.

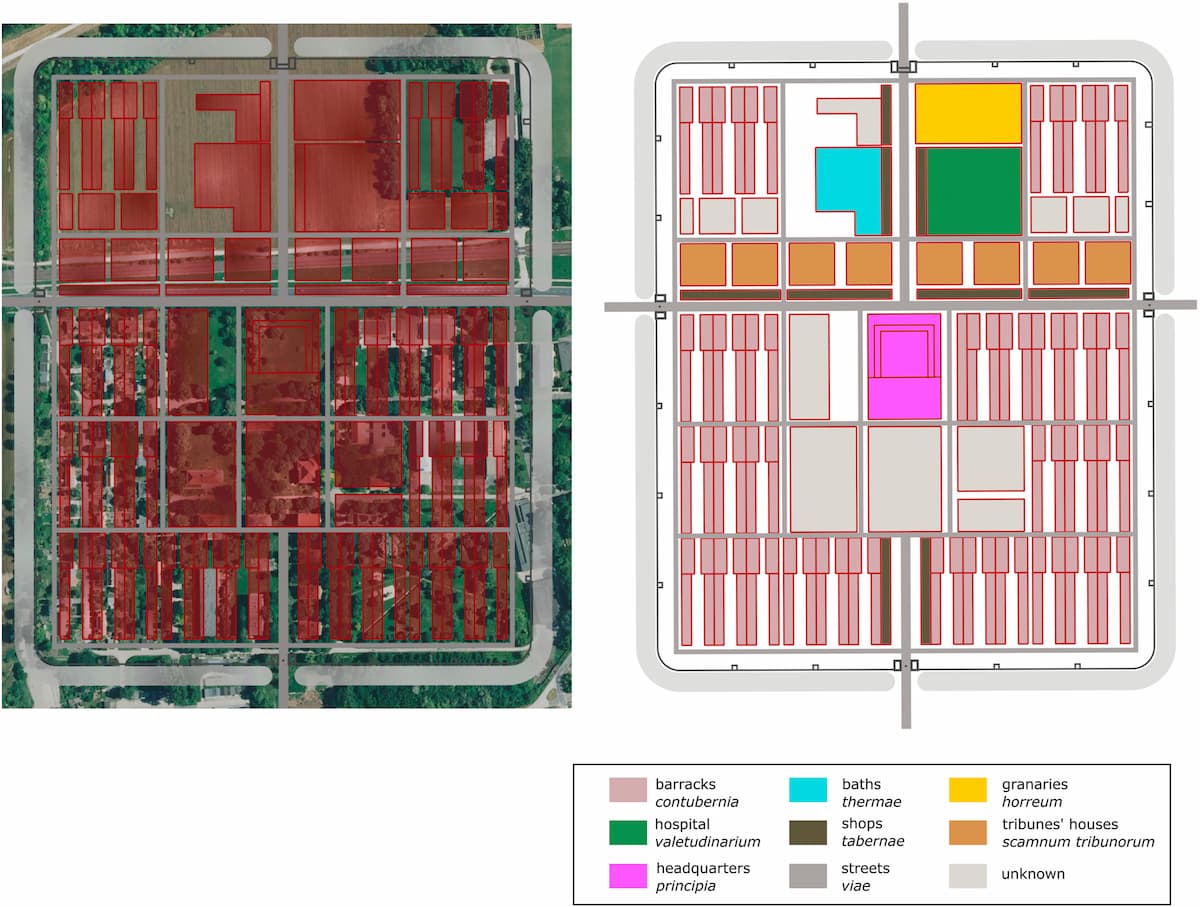

Hypothetical reconstruction of the inner structure of the legionary fortress at Brigetio. Credit: D. Bartus, B. Simon

Hypothetical reconstruction of the inner structure of the legionary fortress at Brigetio. Credit: D. Bartus, B. Simon

The emperor’s anger and the frontier in flames

To understand the importance of the discovery, it is necessary to go back to the previous years. The reign of Valentinian I (364–375 AD) was characterized by an enormous effort to fortify the Danube frontier, known as the Ripa Pannonica. The history of Pannonia in the last third of the fourth century was shaped simultaneously by decisions of imperial policy, border defense measures, and the subsequent barbarian counterreactions, explain the authors of the study.

The spark that ignited the conflict was the construction of a Roman fort in Quadi territory, in a place identified by archaeologists as Göd-Bócsadjtelep. The works, directed by the duke Marcellanus, were perceived as a provocation. To make matters worse, Marcellanus lured the Quadi king, Gabinius, into a trap and murdered him. The revenge of the Quadi, allied with the Sarmatians, was not long in coming. In 374, their warriors swept through the Roman defenses in Pannonia and Moesia, causing massive destruction.

Valentinian I, who was in distant Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier, Germany), set out for Pannonia as soon as he heard of the disaster. After a stay in Carnuntum, he led a punitive expedition described as exceptionally ruthless. By the end of 375, he had established his winter quarters in Savaria and finally moved to Brigetio. His plan was probably to negotiate a winter truce with the Quadi while preparing a new campaign for the spring. But destiny awaited him during the reception of the barbarian envoys.

The death of Valentinian I in an illustration by Wilhelm Sohn (c.1890). Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

The death of Valentinian I in an illustration by Wilhelm Sohn (c.1890). Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

The enigma of the “consistorium”

Ammianus Marcellinus recounts that the Quadi envoys were received in the consistorium. However, this term does not necessarily designate a specific building, but rather any room where the imperial council gathered. After becoming enraged, the emperor was taken to an inner chamber (conclave) so that the barbarians would not witness his agony. The vagueness of these terms has kept the mystery alive for 1,650 years.

Determining with absolute certainty the exact location of the emperor’s death within the fortress is not possible, admit archaeologists Dávid Bartus, Szilvia Jonáczi, and Tibor Négyökrö. We can only identify and list those spaces suitable for the emperor’s winter residence, for council deliberations, or for the reception of envoys.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive our news and articles in your email for free. You can also support us with a monthly subscription and receive exclusive content.

Until now, the main options were the praetorium (the commander’s residence), the principia (the headquarters), or the basilica thermarum (the bath basilica). But the location of the praetorium in Brigetio is uncertain, and excavations in the principia have revealed only poorly built walls and makeshift channels from the late Roman period, which do not suggest an environment fit for an emperor.

The discovery: an imperial reception hall

The key emerged from excavations carried out between 2017 and 2018 in the eastern area of the fortress, known as the praetentura. Beneath the remains of earlier buildings, the team discovered the foundations of a large structure oriented east to west, ending in a semicircular apse.

The apse of the building. Credit: D. Bartus

The apse of the building. Credit: D. Bartus

The building, constructed in the 370s—just in the years before Valentinian’s death—was clearly designed to impress. Its centerpiece was a hall of 101 square meters, closed off by an apse of 56 m², with walls nearly one meter thick. Several smaller rooms were attached to the north and south of the main hall. In a later phase, it was even equipped with a hypocaust heating system (underfloor heating), although the archaeologists note that it was a “rather hastily executed” installation.

But what was this building? Since there are no exact architectural parallels, the researchers turned to analogies. Similar structures with a large vaulted hall flanked by smaller rooms are found in luxurious Roman villas and late antique palace complexes from Hispania to Serbia.

Almost all buildings comparable to the apsidal structure found in Brigetio served a representative function, where the apsidal hall was used for receiving guests and holding banquets, the study notes. Buildings of this type, called “aula” structures, have been identified at sites such as the imperial villa of Mediana (Serbia), a place that hosted imperial visits.

The researchers’ conclusion is clear: Based on its layout and size, the apsidal building discovered in Brigetio would have been suitable for Valentinian I to receive the Quadi envoys.

Unlike other older and possibly deteriorated structures, this building was new, representational in design, and therefore the most logical and dignified place for holding an imperial audience. Compared with the other possible locations mentioned above (praetorium, principia, basilica thermarum), the apsidal building has the advantage of being a newly constructed structure, designed specifically with representational purposes in mind, and would have provided a more appropriate setting for the emperor, the archaeologists state.

An additional mystery: Where was the successor proclaimed?

The death of Valentinian I immediately triggered a succession crisis. Six days later, his four-year-old son, Valentinian II, was proclaimed emperor. However, as with the location of the death itself, the sources are contradictory about the place of the proclamation.

On the one hand, the account of Ammianus Marcellinus implicitly places the events following the death in Brigetio. On the other hand, a different source, the Consularia Constantinopolitana, identifies Aquincum (modern Budapest) as the setting.

The study analyzes this debate and firmly sides with Brigetio. The key lies in the location of Villa Murocincta, the residence of the imperial family, which Ammianus places 100 Roman miles (about 148 km) from the place of the proclamation. If the proclamation was in Aquincum, the villa should be 100 miles from there. If it was in Brigetio, the distance fits almost perfectly with the luxurious and fortified villa at Bruckneudorf, near Carnuntum.

The researchers argue that it is logical that the imperial family, including the young Valentinian II, would have stayed in a safe and comfortable villa near Carnuntum during his father’s military campaign, and not have moved eastward, closer to the theater of operations. Therefore, after the emperor’s death in Brigetio, the high officials would have made the decision there and summoned the boy from Bruckneudorf to be proclaimed in the same fortress.

After weighing the evidence, the team concludes emphatically: Valentinian II was proclaimed emperor in Brigetio.

The discovery of the apsidal building also helps to understand the transformation of Brigetio in late antiquity. The fortress was no longer the classical-era camp, but a reorganized nucleus adapted to the needs of an empire under pressure.

The integration of the latest archaeological, geophysical, and numismatic evidence allows the researchers to come a little closer to the truth of those dramatic days of November 375. Although absolute certainty is impossible in archaeology, the new and majestic hall of Brigetio now stands as the most plausible setting for the last and fatal outburst of Emperor Valentinian I.

SOURCES

Bartus, D., Joháczi, S., & Négyökrű, T. (2025). Where did Valentinian die?: New data on the Late Roman Phase of the Legionary Fortress at Brigetio. Archaeologiai Értesítő. §https://doi.org/10.1556/0208.2025.00121