Roman philosophers and poets, painting by Charles Jalabert. Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

Roman philosophers and poets, painting by Charles Jalabert. Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

Several times now, in different articles, we have referred to a 4th-century AD geographical text that constitutes the oldest description of the Iberian Peninsula from a millennium earlier, as well as of the European coasts from Britain to the Pontus Euxinus (Black Sea). This work is ***[…

Roman philosophers and poets, painting by Charles Jalabert. Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

Roman philosophers and poets, painting by Charles Jalabert. Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

Several times now, in different articles, we have referred to a 4th-century AD geographical text that constitutes the oldest description of the Iberian Peninsula from a millennium earlier, as well as of the European coasts from Britain to the Pontus Euxinus (Black Sea). This work is Ora Maritima, of which only a few fragments have survived, unlike other works by the same author: the Latin politician and poet Postumius Rufius Festus Avienus.

Avienus was born around 305 AD in Volsinii, a city of the Etruscan dodecapolis (league of twelve city-states of Etruria) conquered by the Romans in 364 BC and probably corresponding to present-day Bolsena, although some authors believe it was rather the ancient Orvieto.

He belonged to a senatorial family, the Rufii Festi, and among his ancestors were Gaius Rufius Festus and his sons Gaius Rufius Festus Laelius Firmus and Rufia Procula, as well as Gaius Musonius Rufus (a Stoic philosopher who lived in the 1st century AD, between the reigns of Nero and Vespasian, and was Epictetus’ teacher).

Some sources mention another relative named Avienus who is thought to have been his father. As for family members, we must also mention his wife Placida, with whom he had a happy life and several children. One of them, Rufius Festus, was proconsul of Africa during the reign of Emperor Valens, but before that, he held the position by which he is best remembered: magister memoriae (court historian), a role in which he wrote a work entitled Breviarium rerum gestarum populi Romani, a chronology of Rome from its foundation up to 364 AD that is the first to analyze the formation of the Roman Empire.

Let us return to his father, Avienus, whom some identify with a certain Rullus Festus, corrector provinciae (a sort of civil governor during the Late Empire) of Lucania and Bruttium (an administrative division that was part of the diocese of Suburbicarian Italy, grouping about ten provinces and integrated into the prefecture of Italy). Avienus was twice consul and also held a double proconsulship, first in Achaea (southern Greece) and later in Africa (the Mediterranean African coast from Carthage to Libya inclusive).

There are few details about his personal life, except that he was a man of immense culture and that, despite living in a late period of the Roman Empire, nothing indicates that he professed the Christian faith. In fact, the scarcity of religious allusions in his works might suggest that he was agnostic (though not atheist, a concept that, as we understand it today, did not appear until many centuries later). However, it is impossible to know for sure; one inscription seems to indicate that he was pagan and, believing in fate, a follower of Stoic philosophy. Yet Avienus entered History with capital letters not because of his beliefs or political offices, but thanks to his literary production.

Most of his works survive only in fragments, some larger than others. For example, the thirty-one dactylic hexameters (a type of verse) of the epistle to his friend Flavianus Myrmicus, in which he asks him to send some pomegranates, hoping they will cure his stomach ache.

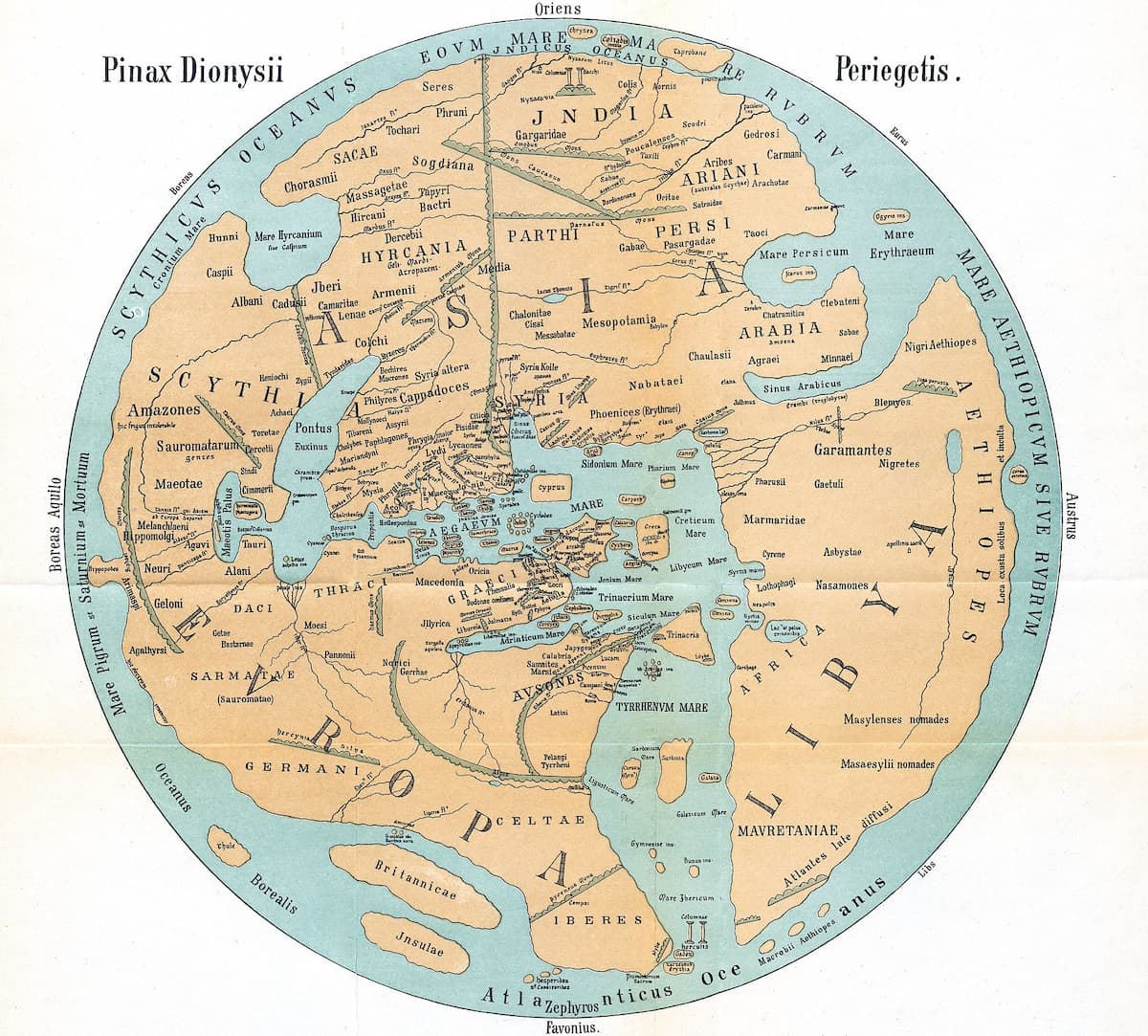

Map of the world made by Konrad Miller in 1898 based on the work of Dionysius Periegetes. Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

Map of the world made by Konrad Miller in 1898 based on the work of Dionysius Periegetes. Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

Or several minor poems such as De cantum sirenum (“On the Song of the Sirens”), of eighteen verses; Ad amicos de agro (“To the Friends of the Countryside”), of nine verses; or De se ad deam Nortiam (“About Himself to the Goddess Nortia”), of twelve verses (let us clarify that Nortia was the Etruscan goddess of destiny and fortune, usually invoked at the New Year by driving a nail into the wall).

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive our news and articles in your email for free. You can also support us with a monthly subscription and receive exclusive content.

Many more hexameters—specifically 1,878—remain from the Aratea, which is the popular name given to his Latin translation—the only complete one that exists—of Phaenomena (“Phenomena”), the didactic poem composed by the Greco-Cilician Aratus of Soli dealing with astronomical and meteorological phenomena visible in the sky.

There also remains the first book—1,393 hexameters—of Periegesis, the work of the Byzantine (or perhaps African) Dionysius Periegetes; its exact title is Descriptio Orbis Terrae (“Description of the World”) and it is written in a very simple language, meant for students, of which Avienus made a version in archaizing Latin.

Dionysius gave his name to an entire genre, the periegesis, or narration of geographical peculiarities based on an itinerary (in this case, the entire inhabited world starting from Alexandria), differing from the periplus in that the latter deals exclusively with the sea and is conceived as a navigation guide.

In that sense, Avienus’ great contribution was Ora Maritima (“The Sea Coasts”), a text he dedicated to his wealthy friend Sextus Claudius Petronius Probus, of which only seven hundred thirteen verses survive and which, as we mentioned at the beginning, contains the earliest written source on pre-Roman Hispania, although it is not limited to that geographic area.

Indeed, Ora Maritima describes the European coasts from Britain to the Pontus Euxinus (the Black Sea), beginning with the ocean and continuing through the Pillars of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar), the Mare Nostrum (the Mediterranean), etc., although the section beyond Massalia (Marseille) has been lost.

This is curious, since the work is based on two predecessors: the Massaliote Periplus, a merchant manual attributed to the 6th-century BC Greek Euthymenes of Massalia (that city being then a Hellenic colony), and another, slightly later text written in the 1st century BC by Ephorus of Cyme.

The lands of the wide world stretch far and wide, and the tide, returning on its course, spreads around the earth. But where the deep sea enters from the Ocean, so that this abyss of Our Sea may form in all its breadth, there lies the Atlantic gulf. Here is the city of Gadir, formerly called Tartessus. Here stand the columns of steadfast Hercules, Abila and Calpe—one on the left of that land; the other near Libya—they whistle with the violent north wind, yet remain firmly in their place.

Avienus, Ora Maritima 80

In fact, Avienus himself explains that he used many sources from different periods, which required him to carry out a demanding task of compilation and translation. Among them we find the Periplus of Himilco and the writings of Hecataeus of Miletus, Scylax of Caryanda, Hellanicus of Lesbos, Pausimachus of Samos, Phileas of Athens, Bacoris of Rhodes, Damastes of Sigeum, Cleon of Sicily, and Euctemon of Athens—not to mention the inevitable Homer and Thucydides. We already mentioned his vast erudition; such was the richness of information he provided on each place that none other than Adolf Schulten used the place names recorded in the work in his search for Tartessos.

It is debatable whether Ora Maritima serves as a reliable historical source, as shown by the fact that it omits mention of a prominent city like Emporium (Ampurias) and instead records others such as Ofiusa, already abandoned by that time, or Cipsela, whose existence is doubtful.

Avienus can no longer account for this, though perhaps he would not have cared much about erring, since when asked why he abandoned urban life to adopt a rural one, he wittily replied: Prandeo, poto, cano, ludo, lavo, caeno, quiesco (that is, “I eat, drink, sing, play, bathe, dine, and rest”). Of course, the quote appears to be apocryphal, taken from Martial.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on November 10, 2025: Avieno, el erudito que recopiló la descripción documental más antigua sobre la Hispania prerromana