Quantitative models show that New Kingdom expeditions in Nubia achieved significant profits, with alluvial mining in streams and the Nile as the most productive sources, challenging previous theories.

A study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science has, for the first time, quantified the profitability of gold mining in Antiquity. The research, focused on the operations of the Egyptian Empire during the New Kingdom in the rich lands of Nubia, reveals that—contrary to what might be assumed—extracting the precious metal was a remarkably lucrative enterprise, mainly thanks to extremely low labor costs.

The work was carried out by Leigh Bettenay and James Ross…

Quantitative models show that New Kingdom expeditions in Nubia achieved significant profits, with alluvial mining in streams and the Nile as the most productive sources, challenging previous theories.

A study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science has, for the first time, quantified the profitability of gold mining in Antiquity. The research, focused on the operations of the Egyptian Empire during the New Kingdom in the rich lands of Nubia, reveals that—contrary to what might be assumed—extracting the precious metal was a remarkably lucrative enterprise, mainly thanks to extremely low labor costs.

The work was carried out by Leigh Bettenay and James Ross of the University of Western Australia. Using mathematical models, the researchers analyzed and compared four different mining methods, concluding that all of them, except one, generated substantial profits.

Under our base case parameters, all models, except distal clast mining (ACM-D), are profitable: they produce more gold than is needed to pay the workers, the study states. The key to this profitability, according to the authors, lies in the fact that the main factor is the low cost of labor in New Kingdom Egypt when valued in gold.

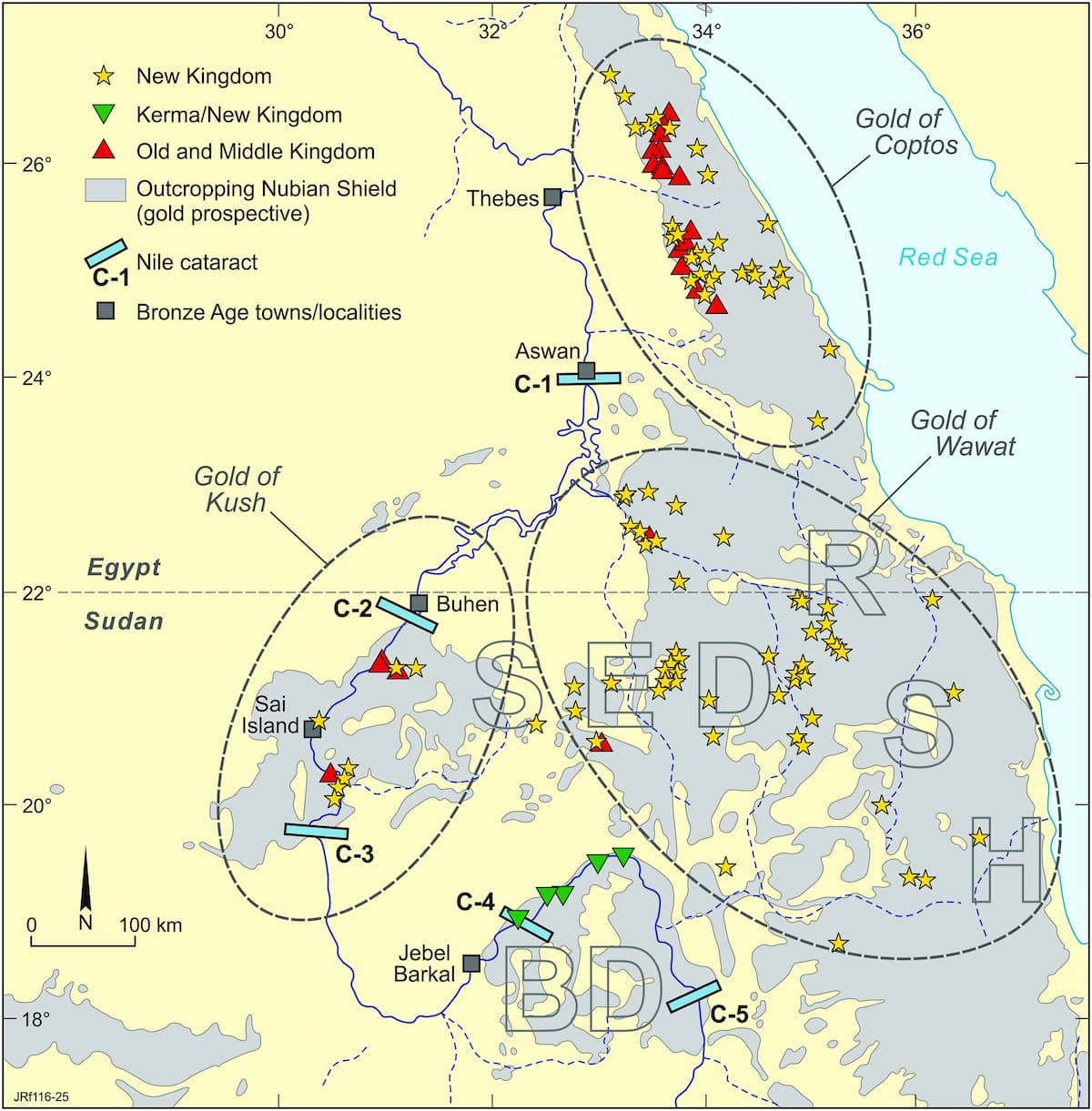

Egypt and Sudan showing gold areas after Vercoutter (1959). Old and Middle Kingdom sites after Klemm and Klemm (2013). New Kingdom mining sites after Klemm and Klemm (2013) and Harrell (2024). Mining sites along the Fourth Cataract are interpreted by Klemm and Klemm (2013) as New Kingdom but as Kerma period by Emberling and Williams (2010). Credit: Leigh Bettenay, James Ross 2025

Egypt and Sudan showing gold areas after Vercoutter (1959). Old and Middle Kingdom sites after Klemm and Klemm (2013). New Kingdom mining sites after Klemm and Klemm (2013) and Harrell (2024). Mining sites along the Fourth Cataract are interpreted by Klemm and Klemm (2013) as New Kingdom but as Kerma period by Emberling and Williams (2010). Credit: Leigh Bettenay, James Ross 2025

Four Ways to Find Gold in the Desert

The researchers designed four representative models of the mining techniques believed to have been used by the Egyptians in Nubia (a region encompassing southern Egypt and northern Sudan):

- Oxidized Lode Mining (OLM): Extraction of the upper, weathered portions of gold-bearing veins in bedrock. It requires breaking rock with tools.

- Primitive Alluvial Prospecting (PAP): Searching for nuggets and free gold particles in sediments from desert stream beds (wadis) near the source. The gold is recovered by screening and washing the gravel.

- Nile Alluvial Prospecting (NAP): Similar to the previous method, but along stretches of the Nile itself, where gold concentrates in favorable spots such as rapids or overflow channels.

- Alluvial Clast Mining (ACM): A peculiar method consisting of manually searching for and selecting quartz fragments containing gold inclusions (“clasts”) within the wadi sediments. These fragments then have to be crushed and ground to release the metal. The authors analyze two variants: near the source (ACM-P) and in more distant, larger catchments (ACM-D), where the gold-bearing fragments are more diluted among sterile sediments.

To estimate productivity, Bettenay and Ross reconstructed the complete operational chain of each method. This includes not only extraction but also transport, crushing, grinding, washing in channels or sieves, and final concentration. Each step consumes time and labor.

Baseline parameters, such as the amount of material a miner could extract or grind in a day, were estimated from historical records of 19th-century miners, observations of modern artisanal miners, and some limited experiments. To make fair comparisons, all models were standardized to a 50-day expedition with a total workforce of 50 people, including not only miners but also haulers, processors, supervisors, guards, and camp staff.

Profitability was calculated by comparing the total gold produced on the expedition with the cost of paying all the workers—valued in gold. If the expedition produced more gold than was needed to pay the workers, it was profitable.

Ancient gold mine in the eastern Egyptian desert. Credit: Roland Unger / Wikimedia Commons

Ancient gold mine in the eastern Egyptian desert. Credit: Roland Unger / Wikimedia Commons

The results showed that the most profitable method was alluvial mining in wadis (PAP), with a Return on Investment (ROI) of 124%. In other words, for every unit of gold invested in wages, 1.24 additional units of gold were obtained. Next came oxidized lode mining (OLM) and proximal clast mining (ACM-P), both with an ROI of 94%. Nile mining (NAP) was also clearly profitable, with a 77% return.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive our news and articles in your email for free. You can also support us with a monthly subscription and receive exclusive content.

The only unprofitable method was distal clast mining in large, distant catchments (ACM-D), which produced a -57% loss. The reason is “dilution”: as one moves away from the primary vein, quartz fragments containing gold become dispersed among vast amounts of worthless sediment, meaning a miner spends days moving earth for very little processable material.

The explanation for this disparity lies in efficiency. The alluvial methods (PAP and NAP) are simple: auriferous gravel is dug up and washed to separate the heavy gold particles. This requires relatively few processing steps. In contrast, the lode (OLM) and clast (ACM) methods require dedicating a large portion of the labor force to the arduous task of crushing and grinding rock or fragments to release the gold. This diverts personnel from extraction, reducing overall productivity.

How could these operations be profitable if the daily output per miner was, in some cases, barely 0.3 grams of gold? The answer lies in the relative value of labor.

In New Kingdom Egypt, a small amount of gold could pay a worker’s daily wage. The study calculates that the daily wage, expressed in gold, was about 0.0455 grams. This figure is roughly twenty times lower than the modern equivalent. This enormous difference in labor cost is what made operations with such modest output by modern standards extremely lucrative for the organizers of the expeditions.

Slaves or Free Workers?

The study addresses the question of slave labor. While an army of slaves would reduce wage costs, the authors argue that this would likely be offset by the need to hire more and better-paid supervisors and guards.

They modeled different pay scenarios and concluded that, although slavery could slightly increase profitability in some cases, the relative ranking among the various mining methods remains unchanged. The fundamental conclusion—that alluvial mining was more profitable—holds regardless of the workforce composition.

One of the study’s most important implications is the potential for extraordinary gains for the “first arrivals” at a virgin deposit. The authors draw an analogy with the gold rushes of 19th-century Australia and California, where early prospectors found nuggets and gravel deposits with extraordinarily high grades (gold concentrations).

View of sector 44 of the Ghozza mining settlement in Egypt, where shackles were found. Credit: M. Kačičnik / Institut français d’archéologie orientale

View of sector 44 of the Ghozza mining settlement in Egypt, where shackles were found. Credit: M. Kačičnik / Institut français d’archéologie orientale

If the New Kingdom Egyptians, during their expansion into previously unexplored Nubian lands, encountered alluvial deposits with concentrations of even 2 or 3 grams of gold per ton of sediment (common in virgin deposits), profitability would have skyrocketed. The model indicates that ROI could have exceeded 5000%.

The findings directly challenge the prevailing theory, defended by experts such as Rosemarie and Dietrich Klemm, that the main source of Egyptian gold came from “clast mining” or “wadi workings”—that is, the selective collection of gold-bearing quartz fragments.

The study conclusively demonstrates that, while this method could be viable very close to the primary veins (within a radius of less than 1 km and in catchments under 0.3 km²), it quickly became uneconomical on a larger scale. Alluvial mining, by contrast, does not suffer from this dilution problem, since free gold particles, being extremely dense, naturally concentrate in “traps” along channels—sometimes kilometers away.

Therefore, the authors argue that the extensive areas of “wadi workings” identified by the Klemms, sometimes extending 5–6 km from the headwaters, cannot be interpreted as clast mining sites. Instead, they propose that these zones were exploited for alluvial gold extraction, possibly using techniques such as coyoting (digging shafts to reach deep auriferous gravels).

The Nile: An Underestimated Source of Gold

The study also highlights the importance of mining along the Nile River, a method the authors describe as “grossly underestimated.” Alluvial mining in the Nile’s rapids and overflow channels (NAP model) had key logistical advantages: proximity to settlements (more security), abundant water for washing, and possibly natural replenishment during annual floods. Recent observations of artisanal miners along the Nile show that this practice, with production levels similar to those modeled, would have been highly profitable during the Bronze Age.

The research paints a new and more nuanced picture of the pharaonic gold economy. Far from being merely symbolic or driven by a titanic, inefficient effort, gold mining during the New Kingdom was a rational and economically viable enterprise.

Egypt’s expansion into Nubia gave it access to virgin gold-bearing territories. There, the first miners did not primarily break rocks or search for quartz fragments in distant wadis, but—just as in nearly every major goldfield in the world—began with the easiest and most lucrative target: the gold that erosion had freed over millennia and deposited as nuggets and dust on slopes, in streams, and in the Nile itself.

Throughout the world’s goldfields, regardless of climate, initial gold production was almost universally dominated by the recovery of free gold particles (that is, alluvial gold), the study concludes. There is no reason to suspect Nubia would have been different. This abundant and easily exploitable source of wealth would have supported the splendor of the New Kingdom, allowing it to accumulate possibly hundreds of tons of gold before production inevitably declined.

SOURCES

Leigh Bettenay, James Ross, The economics of Late Bronze age gold mining by the Egyptian New Kingdom in Nubia. Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 184, December 2025, 106420. doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2025.106420