A study by the University of Aberdeen, based on bone artifacts from the Orkney site, reveals a complex and prolonged cultural transition, dismissing the theory of a violent and abrupt ethnic replacement in northern Scotland.

The official history, consolidated for decades in archaeology manuals, maintained that the Picts, those enigmatic peoples of northern Britain whose intricate symbols endure but whose voice has fallen silent, were wiped off the map by the relentless arrival of the Vikings. A tale of conquest, fire, and iron, in which Scandinavian culture completely supplanted the indigenous one in the Northern Isles of Scotland.

However, that linear and cataclysmic narrative is beginning to crack under the weight of more precise scientific evidence, less indulgent with simp…

A study by the University of Aberdeen, based on bone artifacts from the Orkney site, reveals a complex and prolonged cultural transition, dismissing the theory of a violent and abrupt ethnic replacement in northern Scotland.

The official history, consolidated for decades in archaeology manuals, maintained that the Picts, those enigmatic peoples of northern Britain whose intricate symbols endure but whose voice has fallen silent, were wiped off the map by the relentless arrival of the Vikings. A tale of conquest, fire, and iron, in which Scandinavian culture completely supplanted the indigenous one in the Northern Isles of Scotland.

However, that linear and cataclysmic narrative is beginning to crack under the weight of more precise scientific evidence, less indulgent with simplifications. A new series of radiocarbon datings carried out at the emblematic Buckquoy settlement in the Orkney Islands pushes back the accepted chronology and paints an infinitely richer and more complex picture of cultural interaction, discarding the idea of extermination and opening the door to a process of assimilation, internal change, and prolonged coexistence.

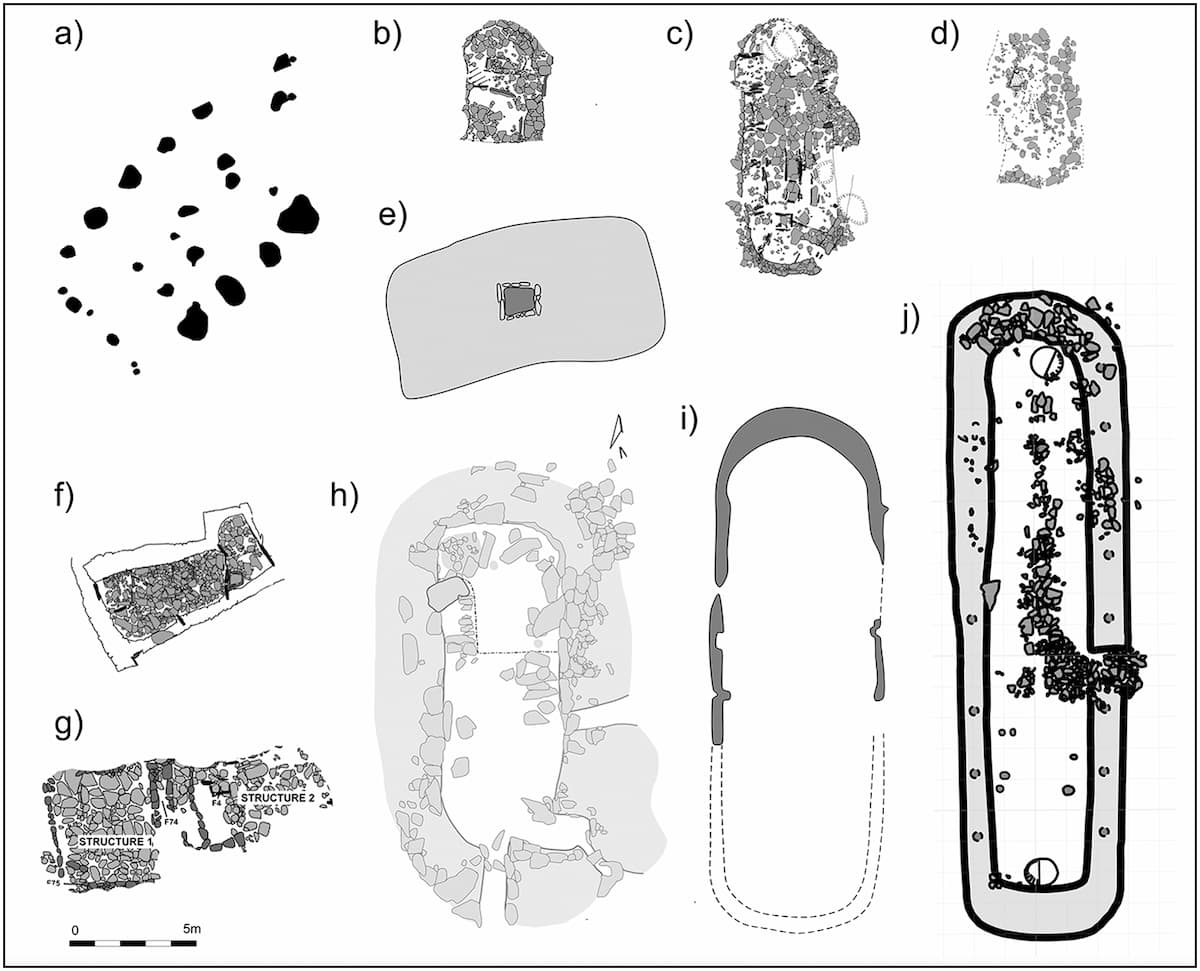

The Buckquoy site has long been a key piece in the puzzle of this transitional period. Two types of radically different architectural structures have been documented there, traditionally used as unequivocal ethnic markers.

Pictish warrior in an illustration from 1857. Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

Pictish warrior in an illustration from 1857. Credit: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

On one hand, the cellular buildings, with complex and compartmentalized floor plans, were associated almost exclusively with the Picts, a term coined by the Romans to refer to the non-Romanized peoples north of Hadrian’s Wall, now used to designate the various groups who inhabited what is today Scotland during the first millennium CE.

On the other hand, the rectilinear structures, with simple and angular forms, have been systematically linked to Viking settlers who began to occupy Orkney and Shetland from the 9th century onward.

This architectural dichotomy served as the backbone of the theory of violent replacement. The original excavators of Buckquoy divided the site into two clearly differentiated phases: an early Pictish period, characterized by cellular architecture, and a later Norse period, defined by rectilinear constructions. Buckquoy thus became the reference sequence, the textbook example that seemed to confirm that the Viking invasion had eradicated the Pictish population, resulting in complete ethnic and cultural replacement.

Nevertheless, this interpretation has long drawn criticism from those who considered it overly simplistic, though the scarcity of absolute chronological data and the paucity of historical sources kept the debate stagnant, leaving the understanding of the Pictish-to-Viking transition in the shadows.

Rectilinear structures from Pictish Scotland. Credit: G. Noble et al. 2025

Rectilinear structures from Pictish Scotland. Credit: G. Noble et al. 2025

The research team led by Professor Gordon Noble of the University of Aberdeen has now managed to illuminate that shadow with the cold, objective light of science. Their work, published in the journal Antiquity, focused on correcting the site’s main deficiency: the near absence of absolute datings. To do so, they subjected a series of bone artifacts—recovered from both Pictish and Norse contexts at Buckquoy and currently housed in the Orkney Museum—to radiocarbon analysis. The subsequent calibration of these dates has produced results that compel a rewriting of the established sequence.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive our news and articles in your email for free. You can also support us with a monthly subscription and receive exclusive content.

The data determine that the Buckquoy settlement was abandoned no later than the early 9th century, a finding that could, at first glance, fit the conquest narrative. The true revelation, however, lies in the start of the so-called Norse period. The chronological evidence places the beginning of this phase between AD 640 and 775, a time span that fully overlaps with the Pictish occupation period. This chronological overlap forces a radical rethinking of what occurred at Buckquoy and, by extension, across the entire region.

In light of this finding, two main interpretations emerge. The first, more aligned with the old paradigm, would suggest that the Vikings annihilated the Picts in this area much earlier than previously believed—perhaps in a precursor raid before the great 9th-century wave—and went on to reuse much of the Pictish material culture for their own purposes. However, the researchers point to an alternative explanation that, according to the data, is far more plausible: that the Picts were not annihilated at all.

This second interpretation rests on a critical reassessment of the archaeological markers themselves. The idea that Picts used only cellular architecture and Vikings only rectilinear is, in itself, an outdated concept. Recent research has conclusively demonstrated that Picts also built rectangular structures.

Therefore, the presence of both architectural types at Buckquoy, now confirmed to be contemporary within a broad timeframe, does not necessarily indicate the presence of two distinct ethnic groups. The most parsimonious explanation, supported by the radiocarbon data, is that all the site’s buildings were constructed and used by the Picts, and that what we see is simply an internal shift in their architectural preferences, a move toward rectilinear forms that became consolidated during the 7th or early 8th century.

This conclusion is not merely an academic nuance; it represents an earthquake for long-held conventions in northern Scottish archaeology. It completely dismisses the idea that the shift from cellular to rectilinear architecture is a reliable indicator of Scandinavian arrival. What was once interpreted as the material trace of an invasion now appears, with high probability, to be the natural evolution of local Pictish society.

Taken as a whole, Professor Noble’s research does not seek to deny the evident Scandinavian influence that eventually permeated the Northern Isles. Norse culture, language, and social structures ultimately prevailed, giving rise to what would later become the Orkney Jarldom. What this study redefines is the nature of that process. Far from being a sudden and traumatic event of replacement, the Scandinavian takeover was likely a long, complex, and uneven phenomenon.

The earliest interactions, in places like Buckquoy, must have been small-scale, sporadic, and based on dynamics of exchange, imitation, or acculturation—processes not incompatible with episodes of conflict, yet radically distant from the myth of eradication. The disappearance of the Picts, if one can even speak of such, did not come with the Viking axe, but rather as a slow twilight—a fading into the northern mist in a process of cultural transformation whose subtleties we are only beginning to glimpse.

SOURCES

Noble G, Griffiths D, Hillerdal C, Allison J, Hamilton D, Batey C. Buckquoy, Orkney: addressing the Pictish-Viking transition in northern Scotland. Antiquity. Published online 2025:1-17. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10231