During the Ediacaran period, approximately between 630 and 540 million years ago, Earth has remained a persistent and puzzling anomaly in the geological record—a magnetic riddle that for decades has resisted scientists’ efforts to find a coherent explanation.

While in earlier and later eras the tectonic plates moved at a steady pace, climates were distributed in predictable zones, and the planet’s magnetic field oscillated moderately around the north and south poles — with occasional reversals…

During the Ediacaran period, approximately between 630 and 540 million years ago, Earth has remained a persistent and puzzling anomaly in the geological record—a magnetic riddle that for decades has resisted scientists’ efforts to find a coherent explanation.

While in earlier and later eras the tectonic plates moved at a steady pace, climates were distributed in predictable zones, and the planet’s magnetic field oscillated moderately around the north and south poles — with occasional reversals — the physics of the Ediacaran simply doesn’t seem to add up.

Several decades of research have revealed wild fluctuations in the magnetic signatures preserved in rocks from that age—a variability not seen in older or younger rocks. This apparently chaotic behavior has posed a major obstacle for researchers, particularly for those using paleomagnetism — the ancient magnetism locked in rocks — to produce accurate maps of continental drift during that crucial period in the history of life.

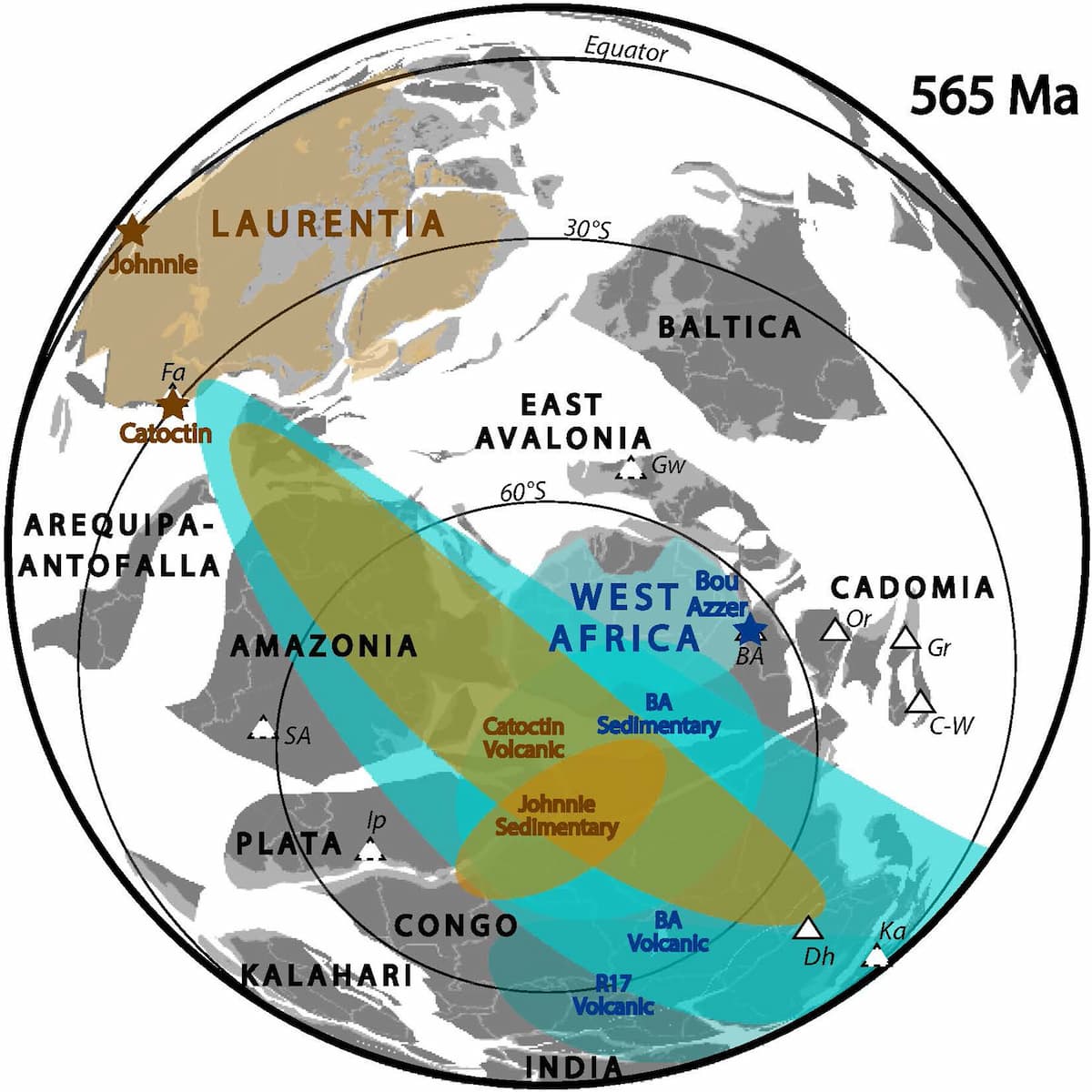

Plate reconstruction of West African Craton (blue) and Laurentia (orange) according to Kent statistical treatment of sedimentary data and Bingham statistical treatment of coeval volcanic data. Credit: J.S. Pierce et al. 2025

Plate reconstruction of West African Craton (blue) and Laurentia (orange) according to Kent statistical treatment of sedimentary data and Bingham statistical treatment of coeval volcanic data. Credit: J.S. Pierce et al. 2025

The theories formulated to explain these fluctuations have been diverse and, at times, conflicting. One line of thought posited that it might be due to unusually rapid movement of the tectonic plates; another hypothesis suggested that the cause could be a rapid shift of the entire Earth under its axis of rotation, a process known as “true polar wander.”

Both ideas, however, faced their own temporal and physical limitations. But what if these magnetic variations were not random at all? What if, beneath an appearance of chaos, there was a global geometry with an underlying order? That is precisely the conclusion of a new study published in Science Advances by an international team of researchers led by Yale University.

We are proposing a new model for Earth’s magnetic field that finds structure in its variability, rather than simply dismissing it as randomly chaotic, explained David Evans, professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and co-author of the new study. We have developed a new statistical method for analyzing Ediacaran paleomagnetic data that we believe will hold the key to producing robust maps of the continents and oceans of that period.

The research focused on a region of exceptional geological value: the Anti-Atlas, a mountain range in Morocco, where co-authors from Cadi Ayyad University identified a series of exceptionally well-preserved and exposed Ediacaran volcanic layers.

The team carried out a meticulous stratigraphic study, layer by layer, of the magnetism in these rocks. The samples, carefully oriented in the field, were transported to Yale for analysis using highly sensitive laboratory equipment. Previous studies of rocks from this period often employed traditional analytical tools that assumed Earth’s magnetic field behaved in the past as it does today, noted James Pierce, a doctoral student at Yale’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the study’s first author. We took a different approach. We were able to determine precisely how fast Earth’s magnetic poles were shifting by sampling paleomagnetism with high stratigraphic resolution and determining accurate ages for these rocks.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive our news and articles in your email for free. You can also support us with a monthly subscription and receive exclusive content.

Collaborators from Dartmouth College, along with research institutions in Switzerland and Germany, provided additional crucial information about the rock layers and high-precision dating. These data showed that the dramatic magnetic changes documented occurred in intervals of thousands of years, not millions.

This temporal finding proved fundamental, as it conclusively ruled out theories invoking extremely rapid tectonic plate motion or true polar wander. Both large-scale geological processes require much longer timeframes—on the order of millions of years—to develop and leave a detectable trace.

In addition to documenting the speed of magnetic variability, the analysis revealed that it possessed an ordered, albeit unusual, structure. Faced with this evidence of an underlying pattern, the researchers devised a novel statistical approach that postulates that the planet’s magnetic poles did not merely oscillate slightly, but wobbled extremely, to the point of swinging across the globe.

This “wobbling pole” model provides a revolutionary mathematical framework for reinterpreting the paleomagnetic data from this period and, ultimately, reconstructing the configuration of the Ediacaran Earth in future studies.

My entire career has been dedicated to mapping the movements of continents, oceans, and tectonic plates across Earth’s surface throughout its history, said Evans, who is also director of Yale’s Paleomagnetic Laboratory. The Ediacaran period, in particular, has represented a major barrier to that long-term goal because global paleomagnetic data just didn’t make much sense. If our newly proposed statistical methods prove robust, we will be able to bridge the gap between the oldest and youngest periods to produce a consistent visualization of plate tectonics spanning billions of years—from the earliest rock record to the present day.