Published on November 11, 2025 1:13 PM GMT

This essay is the result of thoughts developed during the PIBBSS fellowship this summer. Thanks to Dusan and Maris for feedback on a draft of this essay. Thanks to Sahil and Niki for discussions that influenced the ideas of this essay.

1. Intro

What if we could build AI tools to help us navigate the very challenges that AI itself creates?

This is an exciting approach as AI reshapes what’s possible; it makes sense to explore the new intervention it creates. Yet, this path can easily become an empty strategy where one expects AI to magically solve society’s problems. The visuals of AI products carry this imagery with their ubiquitous star-shaped sparks that you also find on laundry detergent pa…

Published on November 11, 2025 1:13 PM GMT

This essay is the result of thoughts developed during the PIBBSS fellowship this summer. Thanks to Dusan and Maris for feedback on a draft of this essay. Thanks to Sahil and Niki for discussions that influenced the ideas of this essay.

1. Intro

What if we could build AI tools to help us navigate the very challenges that AI itself creates?

This is an exciting approach as AI reshapes what’s possible; it makes sense to explore the new intervention it creates. Yet, this path can easily become an empty strategy where one expects AI to magically solve society’s problems. The visuals of AI products carry this imagery with their ubiquitous star-shaped sparks that you also find on laundry detergent packaging. They make you imagine a world made of ease, with problems solved at your fingertips.

I want to talk here about an intervention that goes in the opposite direction: designing AI tools supporting thick practice, tools that don’t attempt to magically dissolve problems, but instead open up new kinds of human expertise.

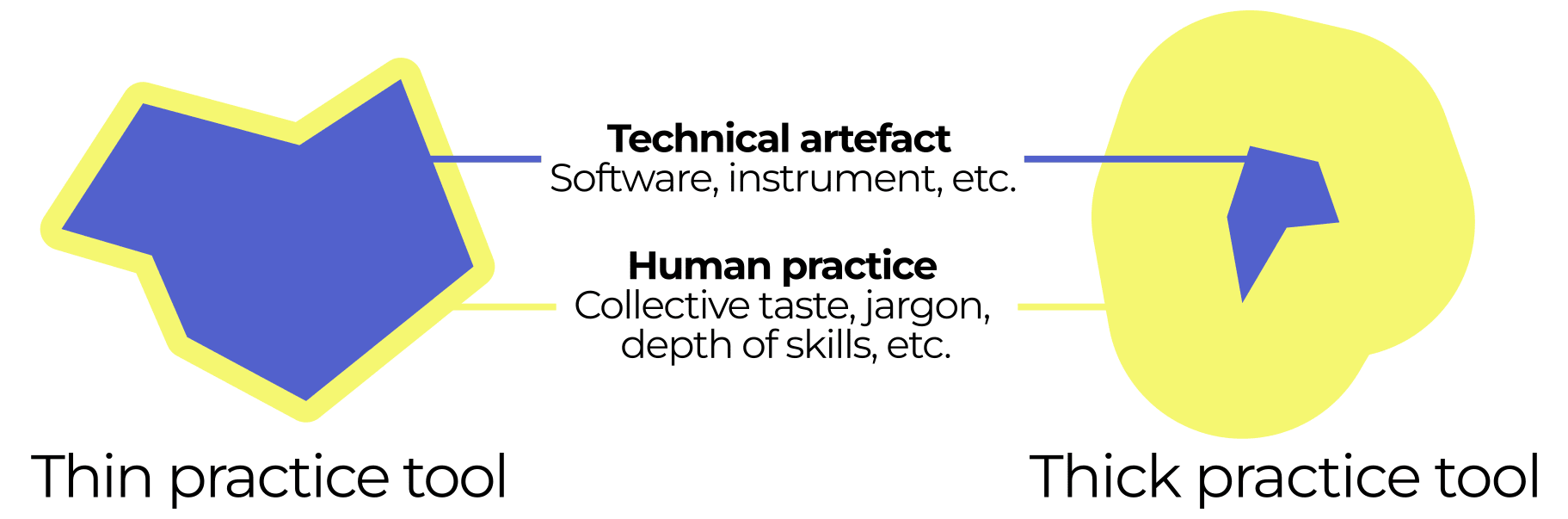

The practice is the surface of contact between the tool and its users, the yellow contour in the diagram below. Some tools create a thin practice. This includes both narrow tools, like hammers, which are designed for a specific use case and require little learning, and very general tools, like a computer, which support diverse use cases equally well.

In both cases, the surface of contact is thin: narrow tools offer little to learn, while general tools alone provide no inherent direction. Users interact with secondary tools that use the general tool as a background infrastructure. For instance, one doesn’t become a computer expert in full generality, but one can be an expert in using specific interfaces with a computer: a programmer, a terminal power-user, or a video-editing expert.

Other tools create a thick practice. Musical instruments and programming languages are prime examples: they allow for open-ended, rich ways of using them while providing clear constraints and a direction for progress, a sense of what constitutes good practice. These tools foster dense, substantial interactions that generate thick cultural layers filled with subcommunities, genres, jargons, aesthetic judgments, and more. In designing thick tools aimed at societal progress, one bets on the impact on cultural evolution rather than problem-solving.

As our technical infrastructure matures to include abundant fluid intelligence, the question becomes: what forms of mastery and skilled practice do we cultivate? Tools don’t just solve problems; they reshape how people think and work together. These transformed practices become the real drivers of long-term societal progress.

My goals in this essay are:

- Adding more granularity to the discussion around AI tools for societal progress by introducing the examples of thin and thick practice AI tools in this domain (Section 2). I propose a model to describe the unique kind of impact thick practice tools have on practitioners at an individual and collective scale compared to thin practice tools. (Section 3.)

- Motivate why thick practices AI tools applied to certain areas like collective deliberation, epistemics, human creativity, or the study of AI behavior are an underrated theory of change. They are more likely to expand human agency than reduce it, and lead to long-term cultural progress, our only way to reach a healthier relationship with technology in the future. (Section 4.).

- Introduce design principles for building tools that can productively absorb hundreds of hours of practice (Section 5.)

2. Thick and thin tools.

2.1 Definitions

The table below illustrates the distinction between thick and thin practice tools. My definition of “tool” is intentionally broad: software like spaced repetition systems, physical objects like guitars, abstract frameworks like the scientific method, or human practices like non-violent communication. While “instrument,” “institution,” or “practice” might fit better in specific cases, I’ll use “tool” throughout to mean anything that augments human capabilities, whether individual or collective.

| Category | Thin practice tool (e.g. calculator) | Thick practice tool (e.g. guitar) |

|---|---|---|

| Collective taste | Step-by-step protocols are enough to guide users. No sense of aesthetics, there is no “beautiful” or “ugly” use of the tool. | Subtle notion of what constitutes a good or bad use of the tool. There is a rich jargon attempting to capture quality criteria, such as code smells in programming. |

| Learning curve | Fast learning curve that saturates after days, sometimes weeks, of daily usage. Spending years using the tool will not lead to substantial gains. | Long learning curves spanning years. Experts with years of training are recognizable power-users. |

| Cost of entry | Immediate utility, intuitive interface usable from the first day. | It can be high. As the learning curve spans years, it sometimes requires months before producing the first valuable results. |

| Diversity | The practice is homogeneous. There are very few variations of the tool. | The tool can support an open-ended practice. Many local variations of the tool exist to support differences in local context. |

The guitar serves as my running example of a thick tool throughout this essay. Learning it requires years of practice along a progression path defined by the musical community. This extended timeline justifies the high entry costs, as newcomers need weeks of sustained effort before they can play a complete song. The instrument supports dozens of distinct practices: flamenco, classical, folk, each with its own variations of the physical instrument. These traditions maintain overlapping yet distinct standards for what constitutes good music, proper posture, and string technique.

A calculator represents the prototypical thin tool counterpart. It is designed for a clear problem with little room for practice to emerge. While edge cases exist (I once programmed my first video game on a scientific calculator), a standard calculator offers minimal room for the kind of sustained practice that defines thick practice tools.

A practice is the set of skills, knowledge, and cultural context that users of a tool create and mobilize during their interaction with it. For instance, a programmer coding a calculator app relies on the thick practice of programming (she is a user of a programming language), but a user of the app will only mobilize a thin practice of the calculator.

By using the dichotomy between thick and thin, I draw from the notion of thin and thick concepts in moral philosophy. While thin evaluative concepts like “good” or “bad” are solely describing normative reasons for actions, and thin descriptive concepts like “water”, “gold” or “mass” are referring to features of the world, bearing no inherent justification for action, other concepts like “courage”, “cruelty” or “kindness” have both descriptive and evaluative content, fitted to specific circumstance while at the same time conveying a clear evaluative stance.

Similarly, thick practices are loaded with inseparable descriptive and evaluative sides, which I refer to in the next section as a know-how (the depth of the execution skills) and the know-what (the taste, the aesthetic judgment guiding the practice). If the niche reference to moral philosophy doesn’t work for you, and reading “thick” brings to mind a curved body, or an idiot, you can replace “thick practice” with “deep practice” or “dense practice” without losing much content.

I will use “societal progress” to refer, first, to the development of collective skills like deliberation, coordination, or epistemics, and second, to collective growth, the development of new values, new culture, and ideologies that go beyond neoliberalism and capitalism to support human flourishing more effectively. While collective skills can be enhanced using technical tools, the second aspect of societal progress is, at its core, human.

2.2 Examples of thin and thick practices tools for societal progress

By applying the distinction introduced in the previous section to tools for societal progress, and in particular coordination and epistemics, here are examples of thick practice tools in these domains:

- Forecasting. The movement began with Philip Tetlock’s tournament on geopolitical and economic predictions. Researchers found that certain participants, dubbed super forecasters, consistently outperformed trained intelligence analysts, despite lacking formal credentials or classified information. What started as an experiment has evolved into a discipline with its own practitioners and institutions. Professional forecasters now number in the hundreds, and platforms like Metaculus or Polymarket collect thousands of predictions daily. The community has built educational resources, offering courses in techniques ranging from Fermi estimates and calibration testing to qualitative methods like information hygiene.

- Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) communities. Groups like Bellingcat analyze publicly available online information to conduct fact-checking and investigative reporting. Their work has documented war crimes in Yemen, Ukraine, and Syria, as well as incidents like the Navalny poisoning. They maintain a set of guides, from geolocalisation of pictures to identification of combatant uniforms in Middle East armed conflicts. The community also organizes competitions to practice skills on realistic challenges, and a repository of toolkits for newcomers.

- Spaced repetition memory systems. These tools use algorithms to schedule flashcard reviews at optimal intervals to maximize recall. Users are creating their own flashcards suited to their context daily. They have moved beyond learning isolated facts from flashcards created by third parties and instead apply these systems to develop a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts, connecting multiple cards to store a network of information pieces, and preserving personal memories. Extensive literature exists on design principles for good flashcards.

- Nonviolent Communication. This practice has no technical component. Developed by psychologist Marshall Rosenberg, this framework offers a structured way to navigate conflict through empathy and clear expression. The practice centers on observing situations without evaluation, identifying underlying feelings and needs, and making specific requests rather than demands. Communities have formed around applying these techniques in diverse contexts, from family mediation to restorative justice programs or hostage negotiation.

- Programming languages. While not strictly a coordination or epistemic tool, programming is the practice used to create many of these tools. Each language creates its own learning pathway and practice. Functional programming, web development, and embedded systems have each developed distinct approaches for humans to shape computing environments. The parallel with musical instruments holds literally, as programming languages can be used as live music instruments.

By contrast, here are several thin tools in this domain:

- Search engine. Though one can become more skilled at searching for information online, spending hours of training will not make you a search engine master. Search engines can be used as components within a larger practice, like OSINT, but they are closer to a piece of infrastructure than an instrument at the center of a dedicated practice.

- Forecasting bots. AI capabilities have enabled the development of forecasting bots, with platforms like Metaculus hosting tournaments that pit bots against each other. Though designing these bots requires skill, the bots themselves don’t open up new areas of practice. They have the potential to produce an abundance of high-quality forecasts on virtually every issue, yet one still needs to develop a process to incorporate these predictions to improve human decision-making.

- X Community notes. These are brief factual statements displayed alongside controversial tweets and selected to be endorsed by users with differing viewpoints. Writing effective notes requires good fact-checking and writing skills to earn “Helpful” ratings from other contributors, making this perhaps the thickest among the thin tool examples. The system’s primary challenge, however, lies in generating a sufficient volume of notes at an adequate speed, not in deepening the quality of notes. While a Top Writer designation exists, it rewards reliability in writing helpful notes rather than exceptional writing skills.

- Blockchain. Like search engines, blockchain functions as infrastructure, a foundation that enables new coordination practices such as DAO governance to develop. Yet, blockchain alone offers no distinct practice to master.

It is fair to say that all these tools brought benefit in terms of coordination and epistemics. However, thin tools are limited in the kind of impact they can bring.

Thin practice tools have historically established the background societal conditions (reduced poverty, improved healthcare, etc.) and the infrastructure (postal service, computers, the Internet, the blockchain) that enable new intellectual work forming thick practices, from the scientific method to programming. These thick practices are not a direct consequence of the new societal conditions or infrastructure; they require dedicated work that is different from the work needed to build the infrastructure.

In designing thick tools aimed at societal progress, one bets on the impact of sustained practice rather than problem-solving. When practitioners form communities around these tools, they create conditions for deeper societal progress. These communities become laboratories where new subcultures emerge and can eventually serve as models for how society might integrate new technologies on a larger scale.

2.3 Examples of thick AI tools

Chatbots are the main interface for using LLMs. But it is still unclear what kinds of mastery this interface can support. The extreme generality of the tool gives the user little affordance to develop a practice, instead relying on intuitions borrowed from human social interaction.

Prompt engineering skills are often developed from scratch through personal practice, with little community around it. Attempts in this direction, like prompt libraries or online courses, are often aggressive commercial strategies leveraging the AI trend rather than a real community of practice valuing mastery. The same goes for image generation tools, where most of the use cases are quick and cheap illustrations without any interactive process.

However, some communities are exceptions to this trend and provide examples of thick practices developed on top of AI tools. They are proof that, despite the fast pace of AI model releases, it is possible to develop lasting skills.

Janus and the LLM whisperers. Janus’ X timeline is a continuous flow of screenshots showing LLM behaving far outside their expected assistant role, from jailbreaks to spiritual insights. While many of the transcripts shared are hard to decipher, it is fair to say that Janus developed a practical knowledge of LLM behaviors that would be impossible to obtain without the thousands of hours they put into interacting with LLMs. They have been reliably providing nuanced descriptions of the personalities of LLM models, creating a base of knowledge to make sense of events like AI-induced psychosis with GPT-4o, or the Claude bliss attractor. There exists a community organized on Discord servers, but most of the activity seems centralized around a few figures Janus or Plini, who mastered the craft.

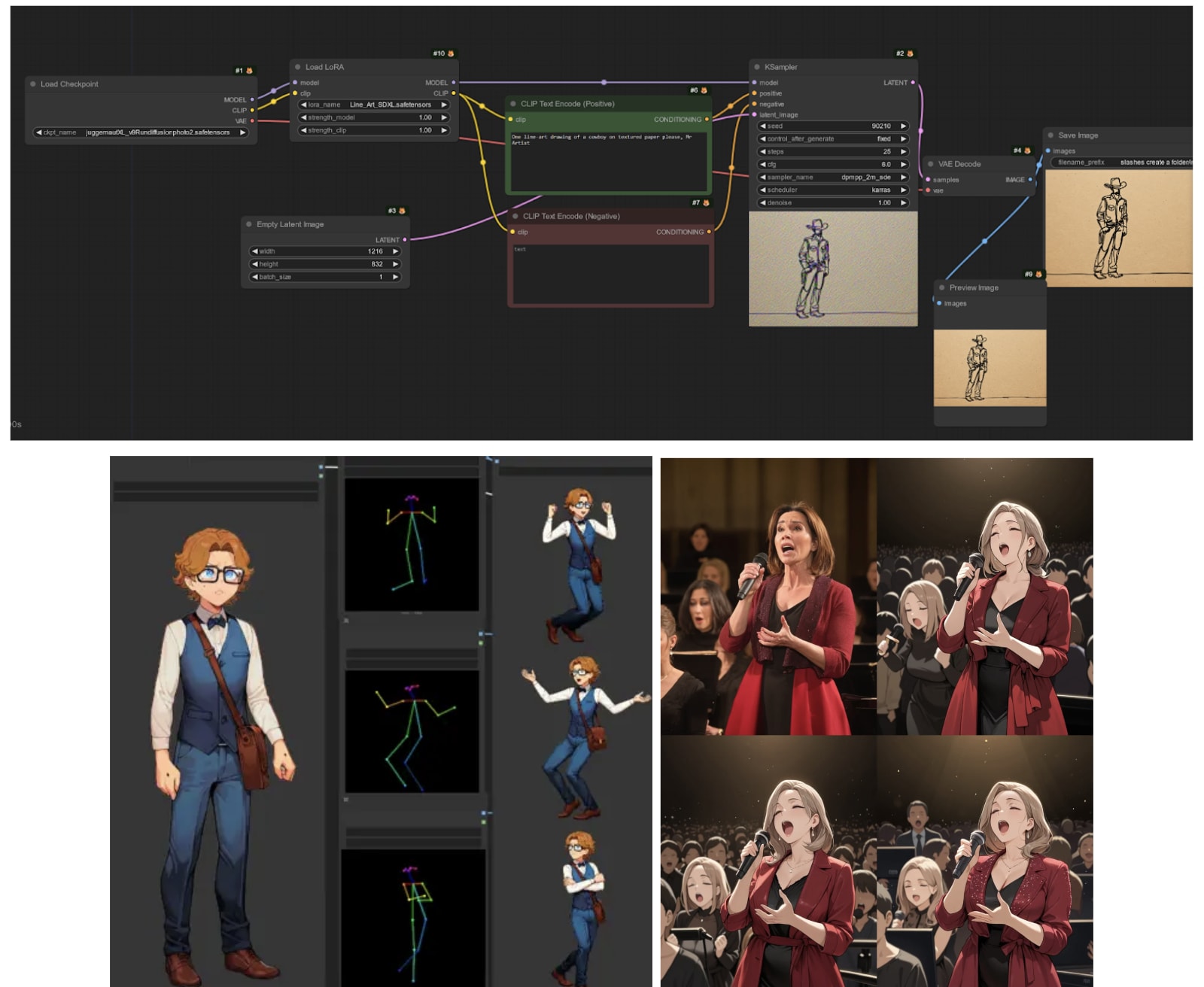

ComfyUI. This is an interface that lets you design AI images and videos by arranging nodes on a 2D canvas. There is an active Reddit forum sharing tips to design complex workflows, optimizing models for local inference, and stacking ›variations of models. One can find examples of impressive control on the generation with local diffusion models, such as consistent character from body sketch or style transfer from anime to realistic.

3. Thick practice AI tools as a promising direction for societal progress

In this section, I discuss the mechanisms through which practice brings change to individuals, to communities of practices, and society as a whole.

In one sentence: thick practice tools bring human agency, as well as cultural and value changes that cannot come from thin practice tools alone. This makes thick AI tools for societal progress an exciting direction for leveraging AI to advance society’s values and skills.

3.1 Thick tools are transformative experiences.

“When you have techniques, the technique will give your ears ideas”

- Jacob Collier, in the documentary The Room Where It Happens

Learning a new skill is often described as learning a know-how. With our running example of the guitar, this means learning the process to play good music, holding the instrument, deciphering a partition etc. This is about learning the generative process to use the instrument.

However, a less visible yet important component of acquiring a new skill is learning the evaluation process. Learning to recognize a good note, a flexible holding of the neck, a harmonious sequence of chords, or a good syncing between voice and notes. All these micro-tastes are channeling your movements to get closer to the overall goal of playing a good song.

In music, it is common for the know-what to be better than the know-how, for instance, when learning to play a song you know by heart. You know exactly what it should sound like, but you don’t yet have the skills to reproduce it. This can create a feeling of stuckness, as you need to keep practicing despite feeling you’re nowhere near where you’re aiming to get.

In other domains, like coding, it tends to be the opposite. After learning the basics of code, you eagerly start your first big coding project. After a few days of development, the codebase becomes a heap of spaghetti code that is impossible to debug. Over the course of practice, you learn the taste of clean code to avoid crashing into a wall of bugs in the future.

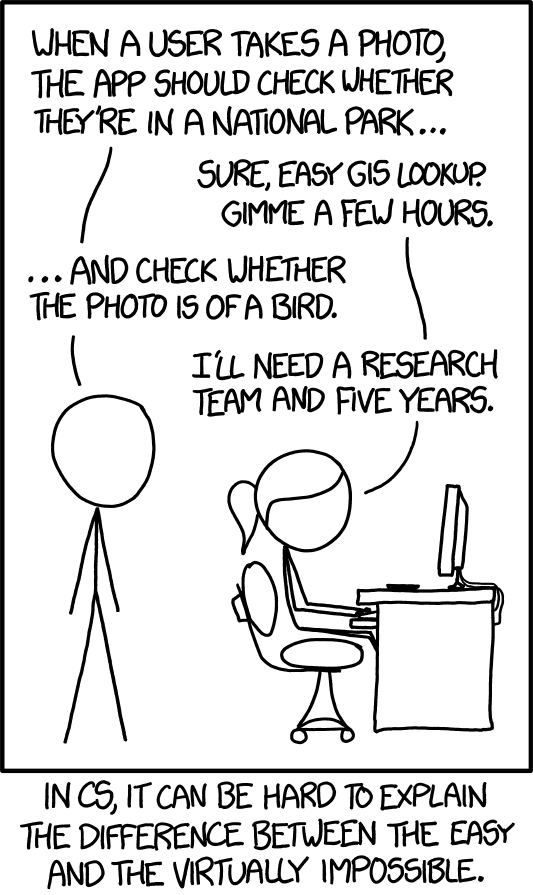

The know-what can also be visible when absent, like this vignette from XKCD featuring the archetype of a manager asking for features disconnected from the technical reality. Their lack of practical experience means they request features that are impossible to realize given reasonable constraints.

The quote from Jacob Collier shows a more macroscopic relation between technique and taste. Having the technique, the ability to execute will shape ideas for what you want to play, what is likely to be your next big project, and end up shaping the trajectories of your craft over the years. Potentially changing the person you become and the values you apply in different parts of your life. At the very least, this is visible from the investment put into the practice. Sustaining a practice over the years means a significant time commitment, and thus means that you now value this practice more than other counterfactual activities.

Following philosopher L. A. Paul’s terminology, this is an instance of a transformative experience. They are experiences that permanently alter a person, including their values, in a way that is almost impossible to imagine ahead of time. While the central examples for transformative experiences are sudden events such as becoming a parent, I would argue that the magnitude of the effect of mastering a practice can be comparable to this, only more diffuse in time. We can see this especially in the arts, where self-descriptions like “I am a musician” or “I am a cook” might bear the same weight as “I am a parent”.

Consequences for thick AI tools for societal progress:

- Potential for societal progress. Thick practices can create new sorts of societal change that thin tools cannot provide, such as initiating new aesthetics and eventually values. They can be a productive grounding for social change movements, following a “show and tell” approach where clear alternatives can be enacted through practice. An example of this double approach is free software activists who both fight political battles to defend their values while developing economically sustainable models of free software development.

- Providing meaning. Thick practices are spaces for self-expression, learning new skills increases your feelings of self-worth, and brings meaning to one’s life. In a world where the default paradigm for AI integration is the replacement of workers with agents, offering space for self-expression and development can be first a strong competitive advantage, and second, more likely to lead to outcomes aligning with human flourishing.

3.2 Practice develops background knowledge

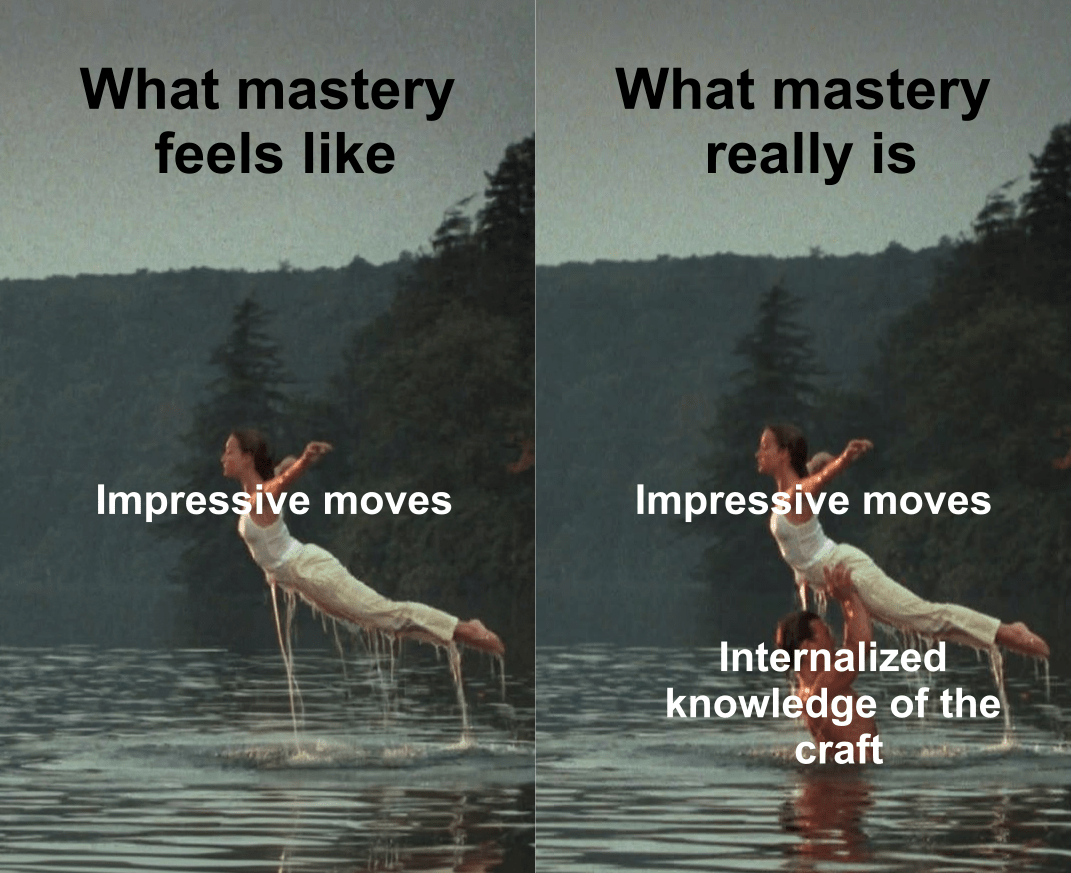

Imagine learning the guitar and focusing on moving your fingers from one chord to another. After a few days of practice, it feels like your fingers move by themselves, and you start directing your conscious effort to another challenge. Movements that are in the foreground at one moment in time get integrated through practice into internalized knowledge, to form background skills that operate unconsciously (the man in the meme above).

This internalized knowledge shapes thoughts (the woman flying in the meme) before they reach conscious awareness. A particularly clear example of this is blitz chess, where players have around 10 seconds per move. Most of the gameplay relies on unconscious decisions about the game.

Beyond acting unconsciously, it is common for a practitioner to have a very bad overall understanding of their learning journey. For instance, it might be impossible for a professional guitar player to remember what it is like to struggle to move her finger between chords. The same is true in the other direction. A novice can’t imagine her mental space filled with consideration of harmony, rhythms that occupy the awareness of her future self.

This makes internalized knowledge the main effect of practice, while at the same time, being hard to notice and access for the practitioner, and even harder to share.

The mind simulation test.

Audrey Tang: […] I really, really wanted a personal computer that I can practice programming on.

Audrey’s mother: Then, one day I saw Audrey there drawing a keyboard on a piece of paper then hitting delete then taking an eraser and erase erase erase erase it all away!

- From the Good Enough Ancestor documentary.

To make internalized knowledge more visible, we can try to remove the tool the skill is associated with, like Audrey Tang replacing a computer with a piece of paper. You can go further, try closing your eyes and imagine yourself using a tool you practiced: musical instrument, painting, graphic design, web design, mathematics, programming, etc.

For programmers, can you write a Python function that takes a list of numbers and returns the list of peaks, i.e. numbers that are greater than both of their neighbors? For visual artists, drawing a scene from the room you are in right now? For musicians, playing your favorite piece with your instrument?

The fact that you have access to a mind simulator, though it might be lossy, is proof of the existence of internalized knowledge that goes beyond propositional knowledge. Somewhere in your brain, there has to be something like the man from the meme above acting in the background and shaping your conscious thoughts so that they reflect the dynamics of the tool.

Consequences for thick practice AI tools for societal progress:

- Untapped territory. New practices can open up previously unexplored regions of human skills and thoughts. The results can be demonstrated to non-practitioners through the production of their practice, like very efficient code, beautiful music, etc.

- Preserving human agency. As practitioners internalize background knowledge, they get a more direct understanding of the effect of their actions and apply a more nuanced and subtle set of preferences. Thick practice AI tools could be a way to scale subtle human attention instead of removing it altogether.

- The ability to mentally simulate a tool is a signal of thick practice. This could guide the development of interfaces for thick practices, and allow filtering design options without having to invest a lot of time into trying to master the tool. More in the last section.

3.3 Communities of practice are sources of cultural progress

The need for communities of practice.

While a talented person can start a new practice alone, a practice impacts the rest of the world when it becomes part of a community.

Communities of practice are spaces where collective taste gets developed and jargon is introduced to share insights from individual practice. As everyone is a practitioner, new words can be used to directly point to the experience of other members. This significantly improves the effective size of experiments that can be conducted, and allows for more efficient exploration of the space of practices.

An important role of communities of practice is the curation of best practices, the dimension of collective taste from the table above. The ability to tell a good from a bad practice is a measure of a community of practice to make progress. Without the ability to curate a practice, the learnings from individual practice of the community cannot compound. The practitioners are directing their practice in different, incompatible directions that cannot learn from each other.

The lack of recognized collective taste can manifest as a crisis where a community splits into subcommunities with their own coherent local practice. It often happens in music when a genre gives rise to sub-genres. In this case, the initial incompatible community gives rise to two incompatible yet individually productive communities.

Cultural progress beyond the community.

The new culture developed within a community of practice moves from local to global scale when a community of practice succeeds in finding a productive direction for progress, and can end up contributing to global cultural evolution.

The most common vector of global change is for the practice to grow and become a recognized resource within the broader cultural sphere. This is the story of Wikipedia growing from an experiment in removing the need for credentials to produce online encyclopedia articles to becoming a primary source of factual information.

As the practice grows, the subculture and the jargon it creates are applied beyond the context in which they were created. This happened, for instance, with:

- The Agile manifesto, and then the Scrum guide, initially developed to navigate software product development, ended up being applied well beyond this domain, from manufacturing to marketing.

- The discovery of the bliss attractor phenomenon from Claude, initially documented by LLM whisperer like Janus, and later acknowledged by Anthropic in their Claude 4 model card, explicitly citing Janus tweets.

- Contemplative practices popularized many now-mainstream words including ‘mantra’ from Sanskrit, entering popular usage in the late 1960s-1970s through Transcendental Meditation, ‘centering’ repurposed by Christian contemplative monks in the early 1970s, becoming mainstream in the 1980s, and ‘mindfulness’ a translation from Buddhist ‘sati’ in 1881, but achieving mainstream popularity only in the 1990s-2010s.

Consequences for thick practice AI tools for societal progress:

- Community over artifact. The core task for designing thick tools involves fostering a healthy community of practice around the technical artifact. This involves skillfully navigating the curation of best practices without killing the organic experimentation that is core to advancing the craft.

- Impact of scaling the practice. Societal progress comes from scaling the practice, not simply diffusing the tool. This requires setting up an accessible curriculum to onboard newcomers and guide them to the frontier of the craft.

3.4 Summary of strategic advantages of thick tools

Practice with thick tools gradually shifts skills from conscious effort to unconscious mastery, shaping what practitioners value and how they see the world. Communities then compound these individual transformations by developing collective taste and new subcultures that can eventually influence the broader society.

Strategically, this means that thick AI tools have an advantage over thin tools because they can enable prefigurative social change, in which new social possibilities are demonstrated through practice rather than argued. They preserve human agency by building intuition rather than replacing judgment with automation, and they create meaningful work and self-expression in a world where AI is seen as a threat.

4. Which thick practice AI tools develop?

Even if we are interested in designing a thick practice tool, there is a lot of room in which kind of tool and practice we want to build. In this section, I discuss why thick practice that incorporates strong interaction with AI tools is an exciting direction, and in which domain one could develop these practices.

4.1 If practice is the target, why the focus on AI tools?

No special software is needed to practice non-violent communication, Montessori education, or even meditation. If many practices contributing to societal progress don’t even need any tech, why want to build new practices around AI?

First, I think there is strong potential in developing new practices that don’t involve any tech. A minimal example is the AI 2027 Tabletop exercise. This is a 4-hour workshop where players role-play actors like government or competing AGI companies for the years leading up to the development of AGI. Even if they are not using AI, the practice is definitely about AI and tries to create enacted knowledge to improve the decision-making of policymakers and AI companies’ employees. I believe there are many practices one can develop to help humans navigate the world as AI progresses that don’t involve any technical component.

However, there are also reasons to create practices that closely incorporate AI:

- Strategic investment. The world economy is pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into increasing AI capabilities. As AI progresses and gets integrated into society, the challenges it brings will accumulate. It is strategic to counterbalance these dynamics by designing thick practices advancing societal progress that also grow as AI gets better, either in depth of practice or in breadth of adoption. Following this reasoning, this means one should try to develop practices that are “hooked” to AI capabilities more likely to develop substantially in the future, such as coding and agentic abilities, instead of, for instance, semantic embeddings that might have reached a plateau in their performance.

- Prefigurative inspiration. Having early examples of communities that embody a healthy relationship with AI, fueling creativity instead of alienation, even in a narrow domain, could help steer the development of AI at a global scale. A few successful examples can inspire ambitious visions grounded in empirical success, and direct human talent and technological development towards a pro-human economy.

- Uncharted territories for human expression. Beyond the bland, helpful assistant or the engagement-seeking AI companion developed by the leading companies, the abundant, cheap fluid intelligence brought by generative models can open a new kind of human expression. We start seeing a glimpse of this with the rise of home-cooked software fitted for a specific local context, potentially a single user. See, for instance, this video of the YouTuber Ben Vallak using AI tools for replacing Apple’s photo software.[1] To extend this vision further in the future, one can think of:

- Improv theater, where entire worlds can be generated on stage as the actors talk and move

- Creating your own locally owned software ecosystem fitted to your habits

- Large-scale deliberation where arguments are translated across frames

- Information economies where contributions advancing collective thinking are tracked and remunerated beyond engagement metrics. This fluid intelligence can be the basis of thick practice that supports human expression, connection, and growth.

4.2 Where to develop thick practice AI tools?

A research agenda of thick practice AI tools for societal progress is beyond the scope of this post. Though I’d like to highlight a few promising areas to develop AI tools supporting thick practice.

Collective epistemics and coordination. Tools in this field would strengthen our ability to get an accurate understanding of our evolving environment and coordinate to prevent societal outcomes nobody wants. Success stories in this field are X community notes, Pol.is’ deliberation platform and forecasting markets. I am particularly excited about tools for epistemics and coordination that go beyond thin tools and help to foster human skills, for instance, by focusing on developing scaffolding rather than agents.

Developing practical agency on AI behavior. Janus and other LLM whisperers like Plini have contributed to the AI discourse by providing a precise vocabulary to talk about the “vibe” of different models. The practice they developed brought qualitative bits of information inaccessible from classic quantitative methods, such as benchmarks. I expect that beyond the study of LLM personas and jailbreaks, there would be many more domains where 1000+ hours of hands-on practice would bring a new understanding of AI behaviors.

Practices supporting human creativity. Thick practices are core to our feelings of agency over our environment and making sense of the world around us. Gen AI is promised a fire hose of unlimited creativity, but we have yet to develop the practice for this generativity to be nurturing to the human soul, and not an explosion of AI slop. There are examples, such as this illustrated article from Amelia Wanterburger, showing that meaningful AI images are possible.

5. Design principles for thick practice AI tools

To finish on a concrete note, here are a few dichotomies of thin and thick tools in the same domain, to attempt to inspire builders interested in designing thick practice AI tools. They all try to answer the question: what makes a tool able to productively absorb 100+ hours of a practitioner’s time?

- Paint vs Photoshop. Interface that allows for human mastery. You could make any image pixel by pixel on Paint, yet Photoshop is a much better interface for developing human control. The theoretical ability of a tool is not as important as the practical usage: which affordance do you give to the user, where does the attention flow, what are the learning loops for humans to learn a deeper and deeper knowledge of the tool?

- Abacus VS calculator. Tools that make your thoughts sharper even when you don’t use them. You can simulate an abacus in your mind, not a calculator. Our spatial processing can be leveraged to translate the task of a complex arithmetic computation into a series of imagined bead moves in a mental abacus. This is a prime example of the mind simulation test, where the integrated knowledge is mobilized literally by simulating the tool.

- WordPress vs ReactJS. Tools for the frontier. Power users of WordPress eventually stop using WordPress and use a professional web development framework like ReactJS. There is value in diminishing the cost of entry to an otherwise inaccessible field like programming. However, if thick practice is the target, time investment is not a bottleneck, and the tool should not compromise the quality of the output compared to competitor tools. In the fields of code and image generation, it is common to see the fast generativity of AI tools trading off with a lowering in the quality of the product. Eventually, one would want to meet established quality bars or define new directions for excellence. For instance, high-level programming languages are not trying to produce high-quality assembler code; they have their own quality criteria operating at another level.

- Triangle vs Guitar. Tools that open new spaces for crafts. There are not many ways to use a triangle, but there is a whole world of playing the guitar. When designing a tool, one can think of all the unexpected ways a user can utilize the tool. As a designer, it is sometimes tempting and useful to reduce the options to direct the attention of the user in a specific way. However, this should be balanced with giving the freedom to repurpose the tools or the practice in ways that were unexpected by the designer.

Further readings & inspiration for this essay:

- ‘AI for societal uplift’ as a path to victory — LessWrong by Raymond Douglas

- Tools for Thought as Cultural Practices, not Computational Objects by Maggie Appleton

- What, if not agency? — LessWrong and the Live Theory sequence.

- How to make memory systems widespread?

- My motivation and theory of change for working in AI healthtech — LessWrong

Discuss