Published on November 5, 2025 10:53 PM GMT

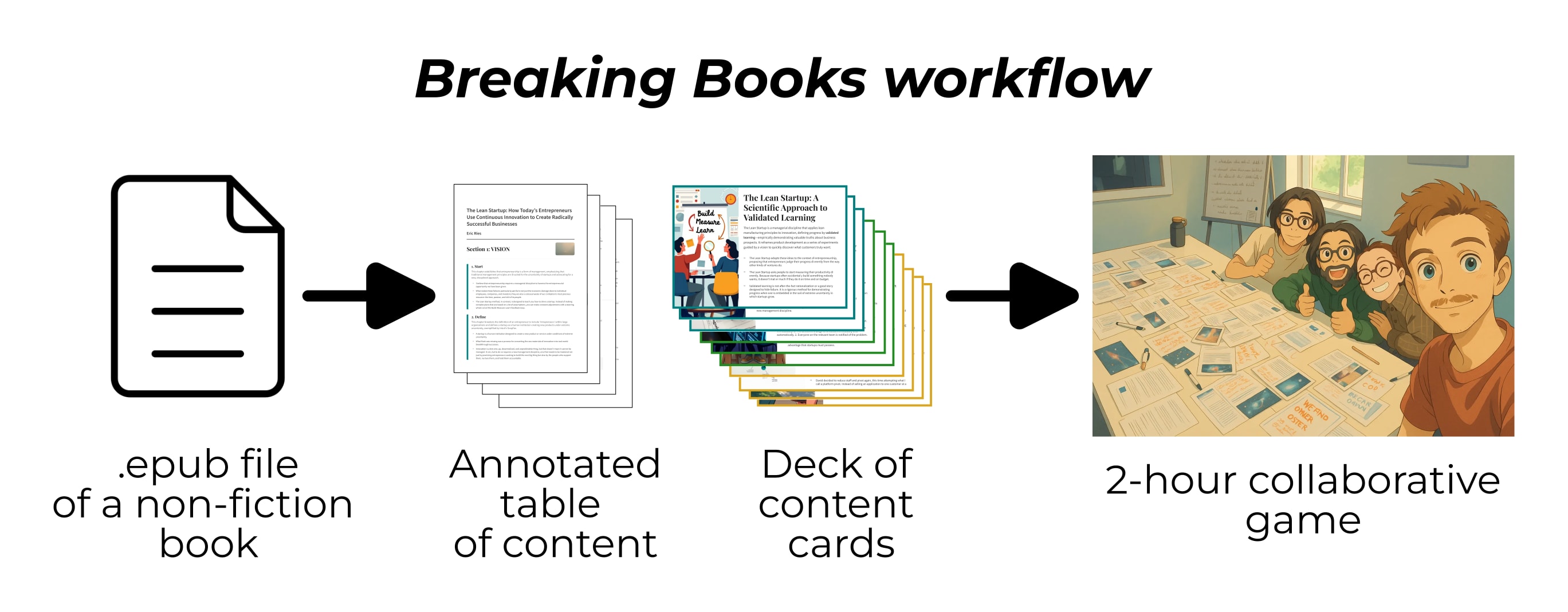

TL;DR. Diego Dorn and I designed Breaking Books, a tool to turn a non-fiction book into a social space where knowledge is mobilized on the spot. Over a 2-hour session, participants debate and discuss to organize concept cards into a collective mind map.

If you’d like to host a session and have questions, I’d be happy to answer them!

The code is open-source, and the tool can be used online.

If you just want to learn about the tool, feel free to skip the first section, and go straight to “Introducing Breaking Books”.

<img src=“https://res.cloudinary.com/lesswrong-2-0/image/upload/f_aut…

Published on November 5, 2025 10:53 PM GMT

TL;DR. Diego Dorn and I designed Breaking Books, a tool to turn a non-fiction book into a social space where knowledge is mobilized on the spot. Over a 2-hour session, participants debate and discuss to organize concept cards into a collective mind map.

If you’d like to host a session and have questions, I’d be happy to answer them!

The code is open-source, and the tool can be used online.

If you just want to learn about the tool, feel free to skip the first section, and go straight to “Introducing Breaking Books”.

Motivation: Books are solitary interfaces.

What an astonishing thing a book is. It’s a flat object made from a tree with flexible parts on which are imprinted lots of funny dark squiggles. But one glance at it and you’re inside the mind of another person, maybe somebody dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, an author is speaking clearly and silently inside your head, directly to you.

- Carl Sagan in Cosmos episode “The Persistence of Memory”

I relate to Carl Sagan’s enthusiasm. Yet another thing that fascinates me about books is how stable the act of reading has been for the past hundreds or thousands of years. We have moved from codices and manuscripts to movable typee to books displayed on screens, but the core experience remains the same. We read, one sentence at a time, monologuing in our heads words written by someone else. I find some peace in that, knowing that beyond all the technological transformations ahead of us, it is very likely that we will still be reading books in a hundred years. Even today’s new means of knowledge production, like Dwarkesh Patel’s podcasts with the biggest names in AI, are eventually turned into a book.

Books bring me this peace and wonder, yes, but also a deep sense of frustration about how constrained they are as our primary interface to the bulk of humanity’s knowledge. They are wonderfully dense and faithful tools to store meaning but have very poor access bandwidth.

This is because reading is like downloading a curated chain of thought from someone else. It is indeed a great feature! It creates this immediate proximity with the author, the assurance that if I spend enough time immersed in this sea of words, I’ll reconstruct the mind that produced them. My frustration comes from the fact that this is our only choice to interact with books. I could run the chain of thought faster, skip some parts of it, but I will have to absorb meaning alone, passively, sentence by sentence.

It sometimes feels like trying to enjoy a painting by patiently following the strokes on the canvas, one by one, until you have the full picture loaded in your mind, or playing a video game by reading the source code instead of running the software.

There has to be other ways to connect with the meaning stored in books. The audiovisual medium has opened such a way. Movie adaptations of books like The Lord of the Rings have been game changers, making a full universe accessible to a broader audience and creating cultural common ground. The same goes for non-fiction, with YouTube videos like CGP Grey’s adaptation of Bruce Bueno de Mesquita’s The Dictator’s Handbook, totaling 23 million views, likely far more than copies of the book sold.

In the past decade, designers and researchers gravitating around the sphere of “tools of thought” have introduced more experimental interfaces. Andy Matuschak has been discussing the inefficiency of books for retaining information (where I discovered Sagan’s quote) and has built his career around what he calls the mnemonic medium, a text augmented by a spaced repetition memory system. Researchers from the Future of Text are even creating immersive VR PDF readers.

These interfaces provide options for how to digest a book, presenting different trade-offs compared to the default reading experience. Movies may be lower in depth but are easier to consume. The mnemonic medium requires extra work from the reader in exchange for longer retention of information.

However, these interfaces remain fundamentally solitary. Learning is supposed to be something we do alone. I believe it doesn’t have to be this way; there is a world of social spaces to create that can make learning a social experience.

I remember many important insights I grokked was while talking to friends, challenged to go beyond the vague pictures of ideas I thought I understood. I learned from countless arguments by embodying opposing points of view, bringing examples, and debugging confusions.

Not only do you leave with a deeper internalization of a piece of knowledge, but you also share a context with your friends. You know they know, and they know you know. Next time, you’ll be able to easily refer back to a piece of this discussion and dive even deeper into the meat of a related topic. These repeated connections form crews, ready to tackle ambitious projects together.

Introducing Breaking Books

A friend and I designed a tool called Breaking Books to turn a non-fiction book into a playground for this way of learning. No participant needs to read the book ahead of time. They will have to mobilize the knowledge from the book on the spot and bring it to life by debating together over the course of a 2-hour session. The goal is not to replace the experience of reading a book but to add a new option to connect with humanity’s greatest body of knowledge.

Breaking Books trades off some depth and immersion into the author’s universe to allow space for social interactions. Sometimes, the best takeaway from a session is an example your friend brought up that you would never have learned otherwise!

In the rest of the section, I describe how a Breaking Books session unfold step by step. Feel free to change some bits and experiment!

1. Before the session: Create and print the game materials ~ 30 minutes.

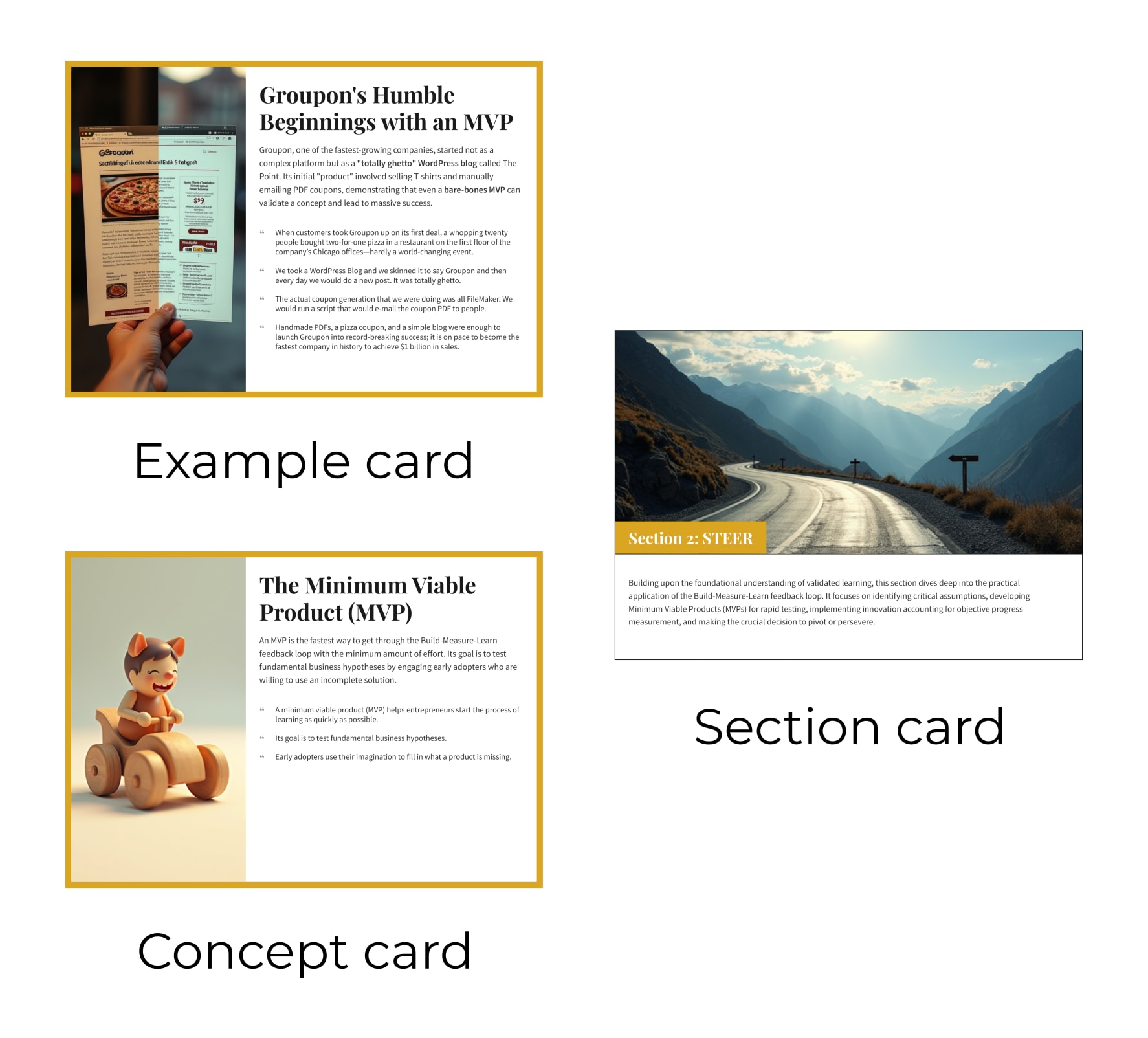

Download the .epub of the book and use the web interface or a self-hosted instance to create a PDF of the game materials. I recommend using 30 cards for a first try, as this allows more space for discussion and discovering the game, and up to 40-50 cards if you have more time available. The PDF contains the content cards (which include concepts and examples), section cards, and the annotated table of contents. Each content card has a title, an image, a short AI-generated summary, and some quotes that have been directly taken from the book. See this PDF for an example of a full game, or refer to the example cards below.

If the event is hosted in person, you need to print the PDF and cut the cards. The cards should be in A6 format. Currently, the PDF contains cards in A5 format, so I recommend printing two pages per sheet for the cards and one page per sheet for the table of contents. If possible, use thick paper with a density of 200g/m² to create cards that are comfortable to handle.

For online events, split the PDF into images. You can use this simple Python file for that. (We plan to improve the interface to make the setup easier for both online and physical events.)

2. Setting up the game ~ 10 minutes.

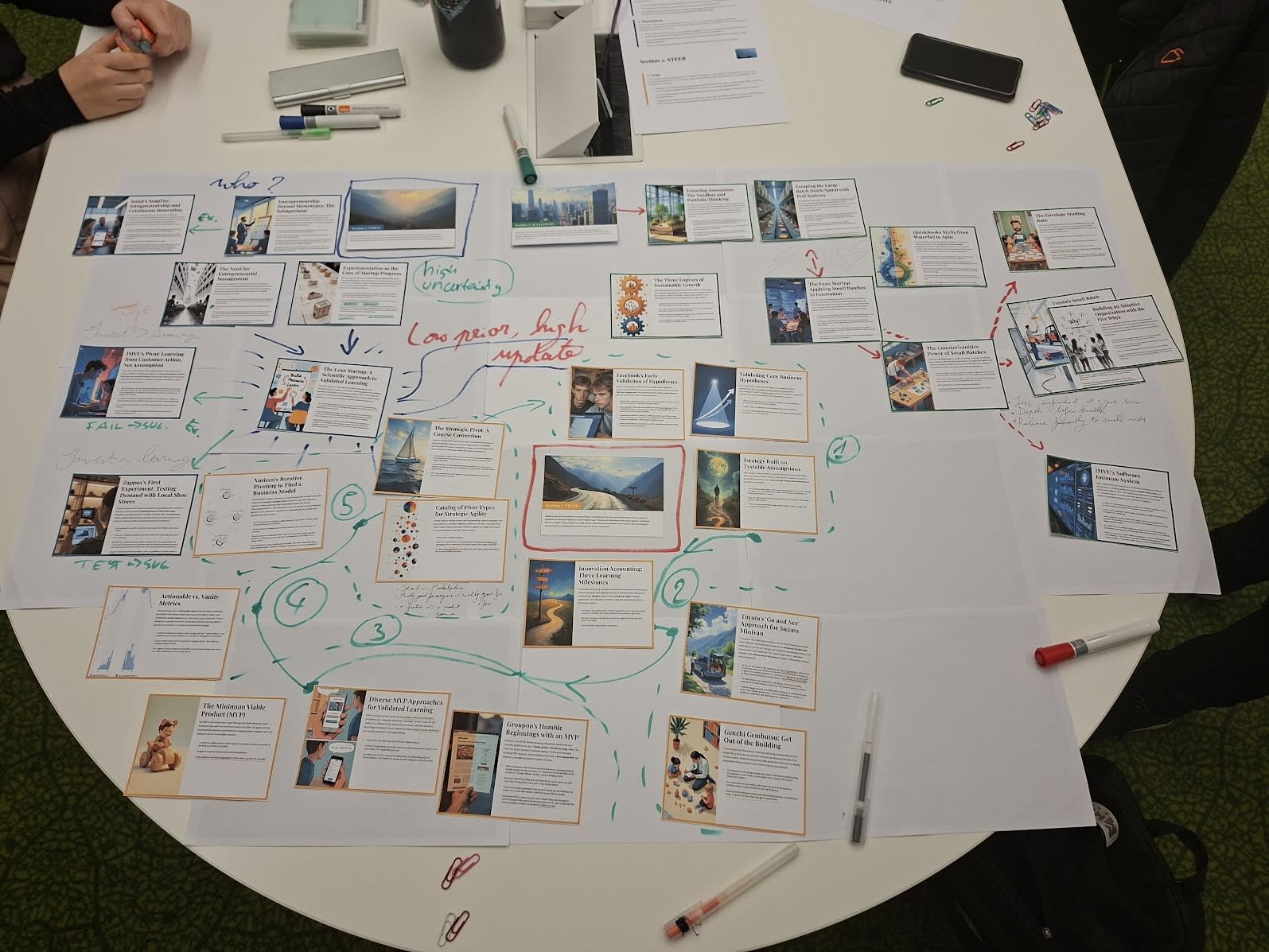

Separate the cards into one deck for each section, placing the section card on top. Find a large table where the cards will be arranged into a mind map, and cover it with paper. I use flipchart paper sheets or A4 pages that I stick together in a grid with tape.

You will need pens to add drawings to the map and highlight elements from the cards. You’ll also need paperclips (or any other small objects) for the appreciation tokens, and a colorful object to serve as the personal opinion stick.

For online events, you can use tl;draw as an online collaborative whiteboard with a minimal interface. No account is needed for your guests; simply share the link and start collaborating on the whiteboard.

3. During the game ~ 1h30

Welcome the participants, allow some time for mingling, and explain the rules of the game. As an icebreaker, you can ask what the participants already know about the book and what they are curious to learn.

Start the session by designating a guide for each section. The guide will be responsible for organizing the layout of the section on the map and telling the story of the section once all the cards for that section are on the table.

For each section, starting with the first, give the section card to the guide of that section. They will read it out loud to open the section.

Distribute the content cards evenly among the participants, allowing around 5 minutes for everyone to read their cards. If a participant finishes reading early, they can refer to the annotated table of contents for more context on the section.

Then, one participant will begin by presenting one of their cards to the rest of the group and placing it on the table. Other participants will follow organically with examples or concepts that relate to the previous cards and place them on the table, connecting to the cards already in place.

There are no strict rules regarding how the cards should be placed or introduced. It is beneficial to start with the most general concepts and add examples later, but the discussion often unfolds naturally. Participants may debate the interpretation of a concept or how the map should be organized, while others might quietly draw on the map or check the table of contents to resolve any confusion.

As the host, your role is to keep track of time to ensure the discussion lasts around 30 minutes per section and to provide space for every participant to speak.

Once all the cards for the section are placed, the guide will take a few minutes to tell the story of the section, trying to connect the cards that have been placed.

Tokens of appreciation. While the participants listen, they can distribute tokens of appreciation (the paperclips in the image above) to show they liked an intervention, such as the presentation of a card or an example a participant brought up from their own experience. The goal is not to accumulate tokens but to maintain a steady flow of exchange. I found it encouraged active listening and incentives quality contributions.

Personal opinion stick. The core of the discussion should serve the story of the book, piecing together what the author tried to convey. When adding personal opinions or bringing in information from outside the book, participants should take the personal opinion stick in their hand. This creates moments of focus, allowing one person at a time to speak, and clearly differentiates between book and non-book discussions.

4. Closing the event ~ 10 minutes

To end the game, take a few minutes to tell the full story of the book, trying to connect as many cards in a coherent narrative. You can close the event by discussing what you learned, whether the expectations of the participants were met, and what their important takeaways are. For the in-person version of the event, participants can bring home a card that resonated with them. And don’t forget to take a picture of the final mind map!

Lessons Learned

Over the summer, I hosted seven Breaking Books sessions with friends—six in person and one online—and played two sessions alone. Overall, this simple prototype we designed in a two-day hackathon with Diego has been a successful experience.

The tool is most useful when you’re curious about a book without wanting to commit to ten hours of reading, and you know friends who would be interested in the book too. It also introduces a new type of event to diversify your hangouts with nerdy friends! The events have consistently been fun moments.

In the end, most participants feel that they could comfortably talk about the book in another context (though I’d like to quantify this more).

During the first sessions, I was too focused on going through the content of the book and discussing all the cards. I have now reduced the number of cards to around 30 and left much more room for personal opinions and information outside of the books. These often end up being the most interesting part of the game.

Takes on the cards: Perhaps the main limitation at the moment is that the cards feel disconnected from one another. The group needs to do a lot of work to bring meaning to the cards, and sometimes the cards don’t really fit into a story or are redundant. I’d like the experience to feel more like completing a puzzle (potentially with multiple options, like the board game Carcassonne), where each card has a place to fit.

A pleasant surprise is that the AI-generated images are often beautiful and diverse. They are frequently relevant to the content of the card and act as visual pointers to identify the concept or example on the map.

However, I am not yet satisfied with the textual content of the cards. They sometimes contain incomplete information or name-drop concepts that are not present in the game material, and we occasionally need to use the Internet to fill in some blanks.

Future directions. There is definitely some improvement to be made in the card generation process to create connection between cards. For instance, we could create groups of “sister cards” when the book introduces a pair or a list of contrastive examples, a common pattern in non-fiction books. However, the more specific the structure, the less it can be applied to a diverse set of books.

So far, I have only tried the tool on non-fiction books, where the goal is to reconstruct the author’s argument. It could be interesting to design a version of the tool for fiction books, creating a playful immersion in the universe and perhaps incorporating some improv games to role-play key scenes.

Organize Your Own Breaking Book Session!

If you’d like to organize a session of Breaking Book, feel free to contact me if you have any questions. I would love to see the tool being used more widely and receive feedback outside of the circle where it has been developed!

I am particularly excited to see how the tool can be used to build depth of connection in a group over repeated use, for instance, by going through five books from the same domain over the course of two months.

Discuss