Published on November 10, 2025 2:53 PM GMT

1. Intro & summary

1.1 Background

In Intro to Brain-Like-AGI Safety (2022), I argued: (1) We should view the brain as having a reinforcement learning (RL) reward function, which says that pain is bad, eating-when-hungry is good, and dozens of other things (sometimes called “innate drives” or “primary rewards”); and (2) Reverse-engineering human social innate drives in particular would be a great idea—not only would it help explain human personality, mental health, morality, and more, but it might also yield useful tools and insights for the technical alignment pr…

Published on November 10, 2025 2:53 PM GMT

1. Intro & summary

1.1 Background

In Intro to Brain-Like-AGI Safety (2022), I argued: (1) We should view the brain as having a reinforcement learning (RL) reward function, which says that pain is bad, eating-when-hungry is good, and dozens of other things (sometimes called “innate drives” or “primary rewards”); and (2) Reverse-engineering human social innate drives in particular would be a great idea—not only would it help explain human personality, mental health, morality, and more, but it might also yield useful tools and insights for the technical alignment problem for Artificial General Intelligence.

Then in Neuroscience of human social instincts: a sketch (2024), I worked towards that goal of reverse-engineering human social drives, by proposing what I called the “compassion / spite circuit”, centered around a handful of (hypothesized) interconnected neuron groups in the hypothalamus and brainstem (but also interacting with other brain regions; see that link for gory details). I suggested that this circuit is central to our social instincts, underlying not only compassion and spite, but also (surprisingly[1]) much of status-seeking and norm-following.

1.2 Summary of this post

The next task is to dive into the “compassion / spite circuit” more systematically, trying to build an ever-better bridge that connects from neuroscience & algorithms on one shore, to the richness of everyday human experience on the other. In particular:

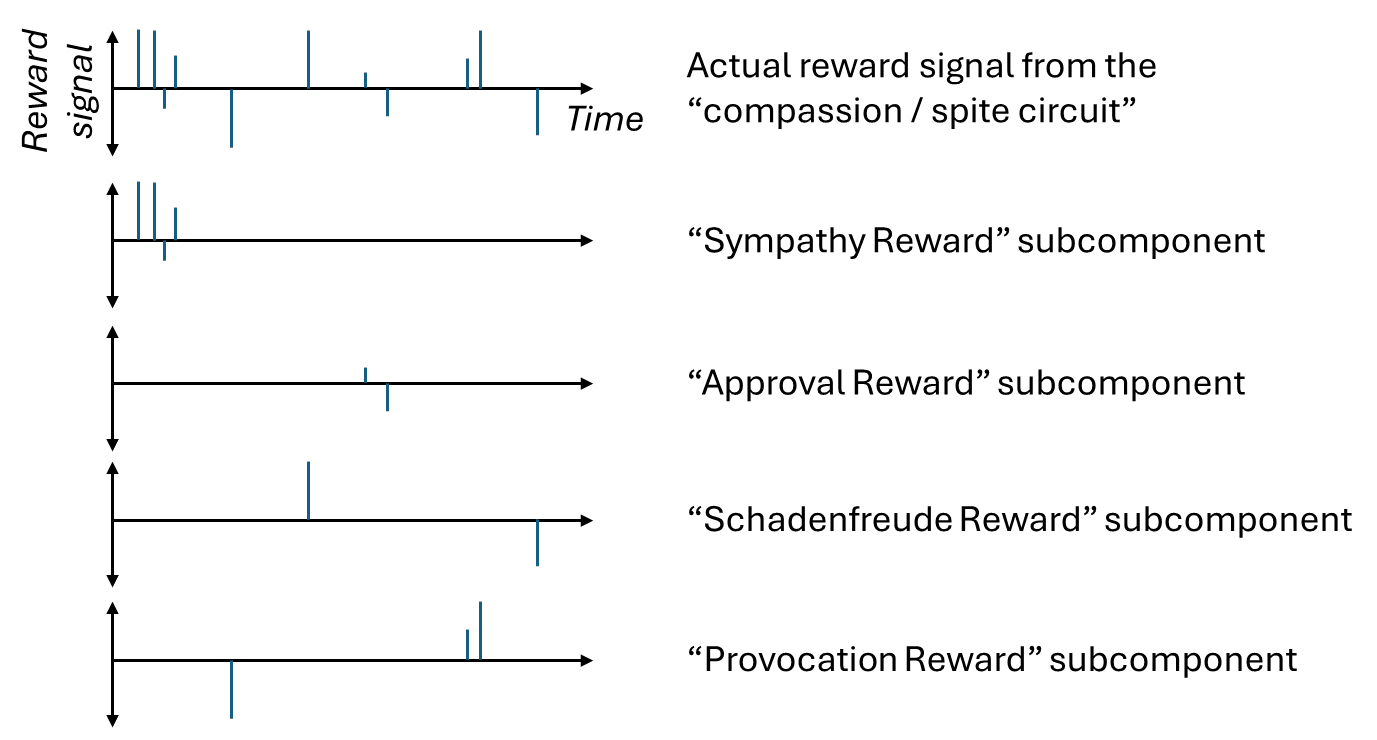

- Section 2 will introduce a framework for thinking about the “compassion / spite circuit”, by splitting it into four reward streams with different downstream effects. I call them “Sympathy Reward”, “Approval Reward”, “Schadenfreude Reward”, and “Provocation Reward”. I also review some theoretical background for how I think about rewards, desires, drives, and so on.

- Sections 3–6 will apply this framework to analyze one of those four reward streams (“Sympathy Reward”), including both its obvious and not-so-obvious consequences.

- Topics include dehumanization, anthropomorphization, “compassion fatigue”, hedonic utilitarianism, The Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics, and more.

1.3 Teaser for subsequent posts

After we finish this post, I have a follow-up post which will analyze “Approval Reward”, a second of those four reward streams coming from the “compassion / spite circuit”.

For the post after that—well, there’s also a third and fourth reward stream, but those are less important from an AI alignment perspective, so I’ll skip those for now. Instead, I’ll pivot back to discussing technical AI alignment more directly.

2. Splitting the “compassion / spite circuit” into four reward streams

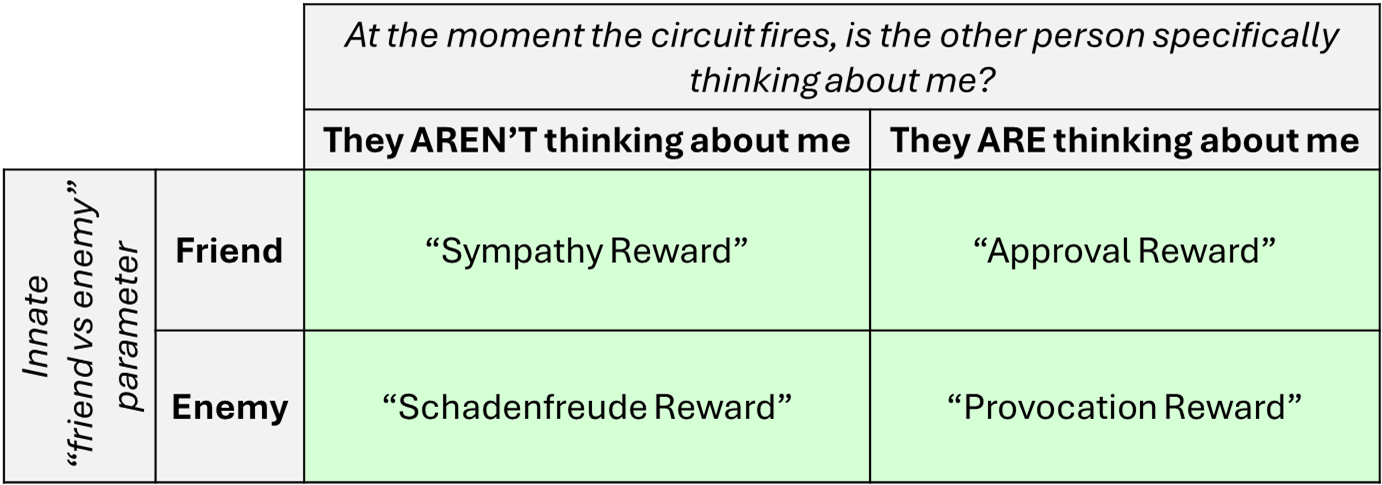

I propose to split up the instances where the “compassion / spite circuit” is spitting out rewards, into four natural categories, depending on:

- (1) the setting of the circuit’s innate “friend (+) vs enemy (–) parameter” (§5.2 of my earlier post), and

- (2) whether or not, when the circuit fires in response to another person, that other person is also thinking about me (§6.1 of my earlier post).

These two choices fill out a 2×2 table, and I’ll make up a suggestive term for each of the four boxes:

Oversimplified gloss on these:

“Sympathy Reward” makes me want to see my friends and idols happy, not suffering.

“Schadenfreude Reward” makes me want to see my enemies suffering, not happy.

“Approval Reward” makes me want my friends and idols to like me rather than hate me; to think of me as impressive rather than cringe; to give me credit for helping them rather than blame for harming them; and so on.

“Provocation Reward” makes me want to pick fights with my enemies.

2.1 Some background and terminology around drives, rewards, and desires

Reward: The brain runs a reinforcement learning (RL) algorithm (see Valence §1.2), with a reward function that sends out reward signals. So “reward” is a signal in the brain, not “physical stuff” in the environment (as Sennesh & Ramstead 2025 puts it). For example, cheese is not a reward per se, but the process of eating cheese will probably cause various reward signals in a mouse’s brain at various times, assuming the mouse is hungry.

Innate drive: I want to reserve this term for circuits in the hypothalamus and brainstem. These tend to be hard-to-describe things that fire in response to hormonal signals and so on, not necessarily tied to any familiar world-model concept. (As an example, see the box near the top of A Theory of Laughter describing what I think “play drive” looks like under the hood.) An innate drive causes reward, which can be either positive or negative (a.k.a. punishment). (So “innate drives” really means “innate drives and/or aversions”) There are probably dozens of innate drives in humans. They are sometimes also called “primary rewards” in the literature, but I don’t like that terminology.[2]

Desires: A “desire” would be a learned world-model concept which was active immediately before a reward, so now it seems good and motivating, as an end in itself (thanks to “credit assignment”). For example, I want world peace, and a nap. An important thing about desires is that they only persist if they capture a real persistent pattern in the reward function. Otherwise, they will promptly be unlearned when they fail to predict reward—see related discussion in Against empathy-by-default, and keep in mind that desires are set and updated by continuous learning, not train-then-deploy.[3] As above, in this post I’ll generally use “desires” as a shorthand for “desires and dislikes”, i.e. both valences.

“Sympathy Reward”, “Approval Reward”, etc.: These are a way to take those hard-to-describe innate drives, and take a step towards making them more comprehensible in terms of real-world concepts (more like desires are), as follows: We imagine listing out all the actual thoughts and situations that trigger a particular innate drive to spit out reward signals, in the actual life of an actual person. We would find that these thoughts and situations fall into (loose) clusters. The reward signals associated with one of the clusters would be “Sympathy Reward”; the reward signals associated with another cluster would be “Approval Reward”; etc.

2.2 Getting a reward merely by thinking, via generalization upstream of reward signals

In human brains (unlike in most of the AI RL literature), you can get a reward merely by thinking. For example, if an important person said something confusing to you an hour ago, and you have just now realized that they were actually complimenting you, then bam, that’s a reward right now, and it arose purely by thinking. That example involves Approval Reward, but this dynamic is very important for all aspects of the “compassion / spite circuit”. For example, Sympathy Reward triggers not just when I see that my friend is happy or suffering, but also when I believe that my friend is happy or suffering, even if the friend is far away.

How does that work? And why are brains built that way?

Here’s a simpler example that I’ll work through: X = there’s a big spider in my field of view; Y = I have reason to believe that a big spider is nearby, but it’s not in my field of view.

X and Y are both bad for inclusive genetic fitness, so ideally the ground-truth reward function would flag both as bad. But whereas the genome can build a reward function that directly detects X (see here), it cannot do so for Y. There is just no direct, ground-truth-y way to detect when Y happens. The only hint is a semantic resemblance: the reward function can detect X, and it happens that Y and X involve a lot of overlapping concepts and associations.

Now, if the learning algorithm only has generalization downstream of the reward signals, then that semantic resemblance won’t help! Y would not trigger negative reward, and thus the algorithm will soon learn that Y is fine. Sure, there’s a resemblance between X and Y, but that only helps temporarily. Eventually the learning algorithm will pick up on the differences, and thus stop avoiding Y. (Related: Against empathy-by-default and Perils of under- vs over-sculpting AGI desires). So in the case at hand, you see the spider, then close your eyes, and now you feel better! Oops! Whereas if there’s also generalization upstream of the reward signals, then that system can generalize from X to Y, and send real reward signals when Y happens. And then the downstream RL algorithm will stably keep treating Y as bad, and avoid it.

That’s the basic idea. In terms of neuroscience, I claim that the “generalization upstream of the reward function” arises from “visceral” thought assessors[4]—for example, in Neuroscience of human social instincts: a sketch, I proposed that there’s a “short-term predictor” upstream of the “thinking of a conspecific” flag, which allows generalization from e.g. a situation where your friend is physically present, to a situation where she isn’t, but where you’re still thinking about her.

3. Sympathy Reward: overview

…Thus ends the first part of the post, where we talk about the four reward streams and how to think about them in general. The rest of this post will dive into one of these four, “Sympathy Reward”[5], which leads to:

Pleasure (positive reward) when my friends and idols[6] seems to be feeling pleasure;

Displeasure (negative reward[7], a.k.a. punishment) when my friends and idols seems to be feeling displeasure;

…which also generalizes[8] to pleasure / displeasure from merely imagining those kinds of situations.

By the way, don’t take the term “Sympathy Reward” too literally—for example, as we’ll see, it not only motivates people to reduce suffering, but also to ignore suffering.

3.1 The obvious good effect of “Sympathy Reward”

The obvious good prosocial effect of Sympathy Reward is a desire to make other people (especially friends and idols) have more pleasure and less suffering.

If you relieve someone’s suffering, Sympathy Reward makes that feel like a relief—the lifting of a burden. Interestingly, in practice, people feel better than baseline after relieving someone’s suffering. I propose that the explanation for that fact is not Sympathy Reward, but rather Approval Reward (next post).

This effect extends beyond helping a friend in immediate need, to morality more broadly. Think of a general moral principle, like “we should work to prevent any sentient being from suffering”. When we do moral reasoning, and wind up endorsing a principle like that, what exactly is going on in our brains? My answer is in Valence series §2.7.1: a descriptive account of moral reasoning. Basically, it involves thinking various thoughts, and noticing that some thoughts seem intuitively good and appealing, and other thoughts seem intuitively bad and unappealing. And I claim that the reason they seem good or bad is in large part Sympathy Reward. (Well, lots of innate drives are involved, but Sympathy Reward and Approval Reward are probably the two most important.)

So that’s the obvious good effect of Sympathy Reward. Additionally, there are a bunch of non-obvious effects, including antisocial effects, which I’ll discuss in the next few sections.

4. False negatives & false positives

There’s some sense in which sympathy “should” be applied to exactly the set of moral patients.[9] In that context, we can consider Sympathy Reward to have false negatives (e.g. indifference towards the suffering of slaves) and false positives (e.g. strong concern about the suffering of teddy bears). Let’s take these in turn.

4.1 False negatives (e.g. dehumanization)

4.1.1 Mechanisms that lead to false negatives

1. Not paying attention: The most straightforward way that Sympathy Reward might not trigger is if I’m not thinking about the other person in the first place.

2. Paying attention, but in a way that avoids triggering the “thinking of a conspecific” flag. This happens if I somehow don’t viscerally think of the other person as a person (or person-like) at all. For example, maybe my attention is focused on the person’s deformities rather than their face. Or maybe I think of them (in a kind of visceral and intuitive way) as an automaton, instead of as acting from felt desires.

3. Seeing the other person as an enemy: As mentioned in §2 above, there’s an innate “friend (+) vs enemy (–) parameter”, and if that parameter flips to “enemy”, then the person’s suffering starts seeming good instead of bad.

4. Seeing the other person as unimportant: This isn’t a way to turn off sympathy entirely, but it’s a way to reduce it. Recall from Neuroscience of human social instincts: a sketch §5.3 that phasic physiological arousal upon seeing the other person functions as a multiplier on how much sympathy I feel, and basically tracks how important and high-stakes the person seems from my perspective. If my visceral reaction is that the person is very unimportant / low-stakes to me, then my sympathy towards them will be correspondingly reduced.

5. Feeling like the other person is doing well, when they’re actually not: Sympathy Reward tracks how the other person seems to be doing, from one’s own perspective. This can come apart from how they’re actually doing.

4.1.2 Motivation to create false negatives in response to someone’s suffering

Sympathy Reward creates unpleasantness in response to someone else’s suffering. This leads to the behavior of trying to reduce the other person’s suffering. Unfortunately, it also leads to the behavior of trying to prevent Sympathy Reward from activating, by any of the five mechanisms listed just above. And this is quite possible, thanks to motivated reasoning / thinking / observing (see Valence series §3.3).

The simplest strategy is: in response to seeing someone (especially a friend or idol) suffering, just avert your gaze and think about something else instead. Ignorance is bliss. (Related: “compassion fatigue”.)

From my perspective, the interesting puzzle is not explaining why this ignorance-is-bliss problem happens sometimes, but rather explaining why this ignorance-is-bliss problem happens less than 100% of the time. In other words, how is it that anyone ever does pay attention to a suffering friend?

I think part of the answer is Approval Reward: it’s pleasant to imagine being an obviously compassionate person, because other people would find that impressive and admirable (next post). Another part of the answer is anxiety-driven “involuntary attention” (which can partly counteract motivated reasoning, see Valence series §3.3.5). Yet another part of the answer might be the various other innate social drives outside the scope of this post, including both love and a more general “innate drive to think about and interact with other people” (see next post).

Averting one’s gaze (literally and metaphorically) is a popular strategy, but all the other mechanisms listed above are fair game too. Motivated reasoning / thinking / observing can conjure strategies to make the suffering person feel (from my perspective) like an enemy, and/or like a non-person, and/or unimportant, and can likewise conjure false rationalizations for why the person is actually doing fine. I think all of these happen in practice, in the human world.

4.2 False positives (e.g. anthropomorphization)

A false positive would be when you waste resources or make tradeoffs in favor of improving the happiness or alleviating the suffering of some entity which does not warrant effort on its behalf. A silly example would be trying to improve the welfare of teddy bears. In my opinion, Blake Lemoine trying to help LaMDA is a real-life example. As another example, some people think that insects are not sentient; if those people are right (no opinion), then insect welfare activists would be wasting their time and money.

Just above I noted that false negatives are not just a passive mistake, but also come along with incentives; if a certain kind of false negative would make us feel better, then we may rationalize some mental strategy for inducing it. In principle, the same applies to false positives. But it seems to be a more minor and weird effect, so I put it in a footnote.→[10]

5. Other perverse effects of Sympathy Reward

(See also “Notes on Empathy” § “What bad is empathy” (@David Gross 2022).)

5.1 Misguided sympathy

More on this in the next post, but Typical Mind Fallacy interacts with the “compassion / spite circuit”, and can lead (especially socially-inattentive) Person A to want Person B to be in situations that Person A would like, rather than situations that Person B actually likes.

5.2 Tradeoffs

If I feel sympathy towards Person A, and thus feel motivated to help them feel better right now, then that’s generally a good thing, compared to callous indifference. But it can also be bad in the sense that, if I’m too motivated to help Person A feel better, then that can trade off against everything else good in the world. In particular, maybe I’ll help Person A at the expense of harming Person B; or maybe I’ll help Person A feel better right now, at the expense of putting them in a worse situation later on.

I think that’s the main kernel of truth in Paul Bloom’s book Against Empathy (2016).[11]

5.3 ‘Hedonic utilitarianism’ bullet-biting stuff

A different set of non-obvious effects of Sympathy Reward is pushing people in the direction of hedonic utilitarians, including all the bullets that actual hedonic utilitarians bite. For example, sympathy gives us a (pro tanto) motivation to toss unhappy people into Experience Machines against their expressed preferences, or to intervene when people are struggling (even if they find meaning in the struggle), or to slip magical anti-depressants (if such a thing existed) into unhappy people’s drinks against their wishes, or (historically) to give them lobotomies, and so on. Sympathy Reward pushes us to do these things, but meanwhile Approval Reward pushes us not to. By and large, Approval Reward wins that fight, and we don’t want to do those things. Still, the pro tanto motivational force exists.

5.4 Incentives and game-theory stuff

If I care about your wellbeing, then you can manipulate me based on what emotions you feel (or if you’re a good actor, what emotions you project). By the same token, I am incentivized to make myself feel (or pretend to feel) feelings for strategic interpersonal reasons. This also applies to Approval Reward (next post).

6. Sympathy Reward strength as a character trait, and the Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics

The Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics is @Jai’s tongue-in-cheek term for the observation that if you interact with a problem, you’ll get widespread condemnation and blame if you don’t solve the problem completely. This is true even if your involvement didn’t make the problem any worse than it already was. It’s even true if your involvement made the problem less bad, while meanwhile the jeering critics were doing nothing. See his post for lots of examples.

I’ll try to explain where this phenomenon comes from, as an example of an indirect consequence of Sympathy Reward.

1. “Strong Sympathy Reward” as a character trait. People differ in how strongly they feel Sympathy Reward. Some see their friend suffering, and are immediately overwhelmed by a desire to make that suffering stop. Others see their friend suffering, and aren’t too bothered.

2. “Strong Sympathy Reward (towards me or people I care about)” as an especially salient and important characteristic, and useful for friend-vs-enemy classification.

If someone has the conjunction of both “Strong Sympathy Reward” and “seeing me [or someone I care about] as a friend rather than an enemy”, then that’s very important for my everyday life. It means that, if I tell them that I have a problem, then they will feel motivated to help me. Everyone learns from abundant everyday life experience that people with this characteristic are good to have around, and to be regarded as friends rather than enemies.[12]

Conversely, if someone lacks one or both of those properties, then that’s also very important for me to know. It means that, if I tell them that I have a problem, they might not care, or they might even look for opportunities to exploit my misfortune for their own benefit. Everyone learns from abundant life experience that people in this category are bad to have around, and should be regarded as enemies.

3. Reading off “Sympathy Reward strength” from someone’s behavior during interactions. Suppose Bob is suffering, but Alice doesn’t know that, or perhaps Alice is out of the country and unable to help, etc. Then of course, Alice won’t help Bob. This is true regardless of whether or not Alice has strong Sympathy Reward towards Bob. So we all learn from life experience that this kind of situation gives us approximately no evidence either way about that aspect of Alice.

On the other hand, if Alice is interacting with Bob who is suffering, then that’s a different story! Now, an observer can easily judge whether or not Alice has strong Sympathy Reward towards Bob, based on whether or not Alice is overwhelmed by a desire to drop everything and help Bob when she interacts with him.

4. Putting everything together. Per above, abundant everyday experience, all the way from preschool recess to retirement book clubs, drills into us the subconscious idea that “Strong Sympathy Reward (towards me or people I care about)” is a key characteristic that distinguishes friends from enemies, and that evidence concerning this characteristic comes from watching people as they interact with me (or people I care about).

When these heuristics over-generalize, we get the Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics. If Alice is interacting with Bob, and Bob is really suffering, and Bob is someone I care about (as opposed to my own enemy), then I will feel like Alice pattern-matches to “friend” if she becomes overwhelmed by a desire to drop everything and help Bob, or to “enemy” if she is interacting with Bob in a relaxed and transactional way, then departing while Bob continues to be in a bad situation.

Jai’s summary (“when you observe or interact with a problem in any way, you can be blamed for it. At the very least, you are to blame for not doing more…”) is tellingly incomplete. If Alice interacts with Bob who is really suffering, and Alice does not fully solve Bob’s problems, then Alice gets credit as long as she “gave it her all” and sobs on live TV that, alas, she lacks the strength and resources to do more, etc. That behavior would be a good pattern-match to our everyday experience of “strong Sympathy Reward towards Bob”, so would be seen as socially praiseworthy.

7. Conclusion

That’s all I can think to say about Sympathy Reward. It’s generally pretty straightforward. By contrast, the next post, on Approval Reward, will be much more of a wild ride.

Thanks Seth Herd, Linda Linsefors, Simon Skade, Filip Alimpic, and Justis Mills for critical comments on earlier drafts.

It’s very elegant that so many human social phenomena, from compassion, to blame-avoidance, to norm-following, and more, seem to be explained in a unified way by the activity of a single hypothalamus circuit. It’s very elegant—but it’s not a priori necessary, nor even particularly expected. There could have equally well been two or three or seven different circuits for the various social behaviors that I attribute to the “compassion / spite circuit”.

There are of course many other social behaviors and drives outside the scope of this post, and I do think there are a bunch of different hypothalamus circuits which underlie them. For example, I think there are separate brain circuits related to each of: the “drive to feel feared”, play, a “drive to think about or interact with other people” (see next post), loneliness (cf. Liu et al. 2025), love, lust, various moods, and so on.

The term “primary reward” tends to have a strong connotation that the “reward” is a thing in the environment, not a brain signal, which (again) I think is a bad choice of definition. For example, papers in the literature might say that a “primary reward” is cheese, and a “secondary reward” is money tokens that the mouse can exchange for cheese.

“Train-then-deploy”—where permanent learning happens during a training phase and then stops forever, as opposed to continuous (a.k.a. online) learning—is actually something that can happen in the brain (e.g. filial imprinting). My claim is more specifically that reward signals update “desires” via continuous learning, not train-then-deploy. For example, if there’s something you like, and then you do it and it’s 100% unpleasant and embarrassing, with no redeeming aspect whatsoever, then you’re unlikely to want to do it again. Or maybe you’ll try it one more time. But probably not 10 more times, if it’s 100% miserable and embarrassing every time. Thus, desires keep updating based on reward signals, even into adulthood.

“Visceral thought assessor” is my term for any thought assessor besides the valence thought assessor (a.k.a. “valence guess”); see Incentive Learning vs Dead Sea Salt Experiment.

Terminology note: I went back and forth between “Sympathy Reward”, “Empathy Reward”, and “Compassion Reward” here. I think it doesn’t really matter. None of the terms {sympathy, empathy, compassion} really have technical definitions anyway—or rather, they have dozens of different and incompatible technical definitions.

Recall from Neuroscience of human social instincts: a sketch that the “compassion / spite circuit” is sensitive to (1) the innate “friend (+) vs enemy (–) parameter” and (2) phasic physiological arousal, which tracks the importance / stakes of an interaction. When these are both set to high and positive, then the circuit fires at maximum power, making us maximally motivated by this particular person’s welfare, approval, etc. My term “friends and idols” is a shorthand for that dependency.

In this post I’m using reinforcement learning terminology as used in AI, not psychology. So “reward” is a scalar which can have either sign, with ”positive reward” being good and “negative reward” being bad. (Psychologists, especially in the context of operant conditioning, use “negative reward” to mean something quite different—namely, relief when an unpleasant thing doesn’t happen.)

The generalization here is upstream of the reward signals—see §2.2 above.

I don’t intend to make any substantive philosophical claim here, like that “moral patients” are objective and observer-independent or whatever—that’s a whole can of worms, and out-of-scope here. I’m merely alluding to the obvious fact that the question of what entities are or aren’t moral patients is a question where people often disagree with each other, and also often disagree with their past selves.

On paper, we should go out of our way to anthropomorphize entities who would seem happy, so that we can share in their joy. But I struggle to think of examples; it doesn’t seem to be a large effect, or at least, it doesn’t pop out given everything else going on. For example, we don’t watch movies where the characters are happy and successful the whole time and there’s no character arc. (Well, I like movies like that, but I have weird taste.)

Ironically, I think the best examples are backwards. As it turns out, there’s a thing kinda like motivated reasoning but with the opposite sign, powered by anxiety and involuntary attention (see Valence series §3.3.5). This leads to something-kinda-like-a-motivation to create false positives in situations where the entities in question would be suffering. Imagine feeling a gnawing worry that maybe insects are suffering at a massive scale, and you can’t get it out of your head, and your mind constructs a story that would explain this gnawing feeling, whether or not the story was true.

I agree with Bloom on most of the practical takeaways of his book: people should be more impartial, people should do more cost-benefit analyses, etc. On the philosophical and psychological side, I think Bloom is mistaken when he argues that the so-called “rational compassion” that he endorses has no relation to the “empathy” that he lambasts. My take is instead that the latter is a big part of what ultimately underlies the former (i.e. the Sympathy Reward part, with Approval Reward being the rest). See §3.1 above.

I’m a bit hazy on the details of how the innate “friend vs enemy parameter” is calculated and updated. But if someone resembles people who have made my life better, then I’ll probably feel like they’re a friend, and conversely. See Neuroscience of human social instincts: a sketch §5.2.

Discuss