Published on November 3, 2025 4:43 AM GMT

I.

I have claimed that one of the fundamental questions of rationality is “what am I about to do and what will happen next?” One of the domains I ask this question the most is in social situations.

There are a great many skills in the world. If I had the time and resources to do so, I’d want to master all of them. Wilderness survival, automotive repair, the Japanese language, calculus, heart surgery, French cooking, sailing, underwater basket weaving, architecture, Mexican cooking, functional programming, whatever it is people mean when they say “hey man, just let him cook.” My inability to speak fluent Japanese isn’t a sin or a crime. However, it isn’t a virtue either; If I had the option to snap my fingers and inst…

Published on November 3, 2025 4:43 AM GMT

I.

I have claimed that one of the fundamental questions of rationality is “what am I about to do and what will happen next?” One of the domains I ask this question the most is in social situations.

There are a great many skills in the world. If I had the time and resources to do so, I’d want to master all of them. Wilderness survival, automotive repair, the Japanese language, calculus, heart surgery, French cooking, sailing, underwater basket weaving, architecture, Mexican cooking, functional programming, whatever it is people mean when they say “hey man, just let him cook.” My inability to speak fluent Japanese isn’t a sin or a crime. However, it isn’t a virtue either; If I had the option to snap my fingers and instantly acquire the knowledge, I’d do it.

Now, there’s a different question of prioritization; I tend to pick new skills to learn by a combination of what’s useful to me, what sounds fun, and what I’m naturally good at. I picked up the basics of computer programming easily, I enjoy doing it, and it turned out to pay really well. That was an over-determined skill to learn.

On the other hand, I’m not at all naturally good at music and for most of my life there wasn’t really any practical use for it, so I’ve spent years very slowly acquiring a little bit of musical skill entirely when it was convenient and fun. I haven’t learned even a single word of Swedish, nor the 101s of scuba diving.

Let me restate what I said above; my ignorance is not a virtue.

Some skills are hard to appreciate unless you have some prerequisite amount of the skill yourself. Take music for an example; before I had any musical training, I could nod along to tunes but had no idea of what pieces would be harder or easier and didn’t notice the difference between a flat and a sharp. After spending a few weeks with progressively trickier bass riffs and power chords, I gained the ability to listen to a metal song or watch a video of a guitarist and realize what I was watching was impressive.

Consider computer programming; almost a decade passed between me learning how to do a for loop and learning what a computer scientist means by space and time.[1] Before I learned about big O, I had a vague idea of some code being faster. Afterwards, I could have my jaw dropped by an especially efficient twist of clever code. If you do not have a skill, you may not notice what you don’t have. It’s a little like being colour blind; the skilled designer is wincing at the clashing colours you picked and the low contrast background and foreground of your website and you don’t yet see the problem.

Once you have a skill, often it’s actually easier to do it well than to do it badly. I naturally spell English sentences correctly. If I try to mispll wards nand mac thas sentnce rong, I have to actually stop and force myself not to simply type out what I was thinking. That doesn’t mean that I never make mistakes, but they’re either rare typos or uncommon words I don’t use often. If you’re bored and have a mildly sadistic bent, it can be fun to ask well trained singers to sing off key. Try asking serious weight lifters to use poor form; they’ll usually outright refuse.

So; there are lots of skills, it’s fine to not have all of them, if you don’t have a skill you might not realize what you’re missing, and if you’re good at a skill then doing it well is often easier than doing it badly. With me so far?

II.

This essay is a response to Lack of Social Grace is an Epistemic Virtue.

My summary of LoSGiaEV: is that social grace and honesty are in conflict, sothus idealized truth- seeking people would not have the polite niceties of common societyin say, American norms. You can either be graceful or honest, and steps towards one direction are steps away from the other. The ideal rationalist would be perfectly honest, and this would involve very little social grace.

I disagree with this.

If people say that you’re rude, obnoxious, or off-putting, then it could be you’re making a deliberate tradeoff, but it could also be you lack the skill of being polite or nice. If you lack the skill of pro basketball, you’re not surprised when you can’t make the team.

That’s fine. But — If they say this and it surprises you, then I’m confident there’s a skill you don’t have. If you’re confident you know when you’re being rude, and you can usually guess what people are going to be annoyed at, then you might have the skill.

Yes, being polite is an extra constraint on what you can say. Spelling your words correctly is an extra constraint on writing. Good writers usually do it anyway. Unless you are trying to get people mad at you for some reason, people being mad at you seems like a cost.

Social grace and clear honesty do come apart at the tails I expect, but the overwhelming majority of the time — 95% of the time at least, possibly as high as 99% — there’s a way to say what you want to say both gracefully and honestly. Maybe you can’t find it in the moment. Maybe I couldn’t, I’m not claiming to be a master of this. But I’ve observed enough people make what seem to me to be unforced errors here that I feel confident saying people aren’t actually at the Pareto frontier here.

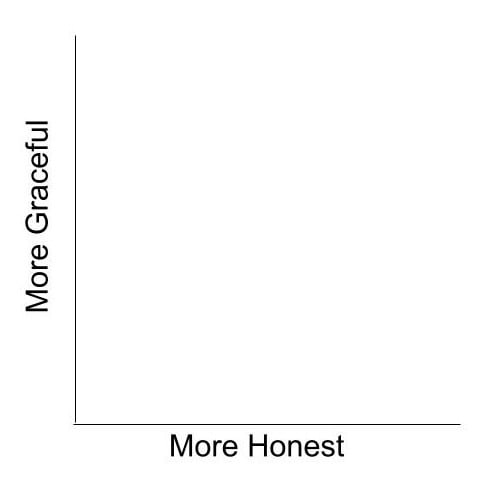

You can’t make everyone happy with you all the time and you shouldn’t try. Or, in local parlance, avoiding anyone ever being mad at you is a poor terminal value! Sometimes any way of expressing something true to someone will tick them off. But there isn’t a slider from More Graceful to More Honest like a slider from -5 to 5 on a number line. Reductio ad absurdum, “your shoe is untied you complete fuckwit” will predictably annoy someone even if it’s true, and “you look ready for our jog!” isn’t charming or pleasant if it’s a lie and they trip and fall on their face thirty seconds from now.

The way to test this is to try being polite and not rude for a little while, especially if you can do it around a new group of people who won’t be thinking of your past reputation. That said, if people say you’re rude and you are not surprised, I’m less confident you don’t have the skill.

Where does that leave people who lack the skill of being polite and nice to others? Well, they don’t have to learn it. I’m not going to learn Chinese any time soon. If people say I’m ignorant of Chinese, well, they’re right.

III.

In The Third Fundamental Question Of Rationality, I told the following story:

When I was a teenager, I had a classmate who loved horses. She had pictures of horses on her backpack. She drew horses in the margins of her notebooks. She talked about horses at lunch. I didn’t find horses interesting, but I liked hearing people talk about what they knew a lot about, and wanted to make friends. I was not, however, socially adroit, so what I said was “why do you care about something boring like horses?”

She complained to the teachers about me being rude, which in hindsight was entirely fair. This was one of several turning points that made me realize I was obnoxious and irritating without intending to be. I still like hearing people talk about their fields of interest, but these days I usually phrase the question as “I don’t know much about that subject, can you tell me more about it?” or “so what subject are you fascinated by?” More generally, before I speak I ask myself what I’m about to say and how I think the person I’m talking to is going to react next. If I had asked myself ahead of time what I thought the response would be to calling a subject she was obviously interested in boring, I would have said something else.

This is a pure tactical mistake.

I didn’t get more information this way. I wasn’t more honest by being more graceful. This is not a linear scale.

My lack of social graces cost me without purchasing me any extra truth. Instead of a linear scale, I think social grace and honesty are two axes upon which you can improve.

The bottom left corner, lacking in both honesty and grace, is when you tell someone they’re a moron when they’re actually a genius in the process of correctly proving a new theory. The top left corner, full of social graces but lacking in honesty, is when you let down a repulsive suitor so gently they lose track of the fact that they were asking you out. The bottom right, full of honesty and lacking in all grace, is when you say in front of your date that you don’t think they’re attractive. And the top right, ah, there is the place where skill abounds.

I could have drawn this as a Pareto frontier, with a line moving from the top left to the bottom right. I deliberately didn’t do that, because I think the line can move as you practice. Just as exercising your muscles lets you carry heavier weights, practice in social grace lets you communicate things to people and have them be grateful to you where previously they’d be angry at you.

Lest I be misunderstood, I think there is a skill to being honest. It doesn’t come naturally to many people, and there are perhaps some connected ways that honesty can come easily when grace comes hard. But not that much correlation. I suspect that it’s a little like the relationship between math SAT scores and writing SAT scores; anti-correlated on a college campus, since the college was looking for people with a certain summed score, but correlated everywhere else since there’s a common factor. [2]

And once you’ve practiced for a while, grace doesn’t take as much effort as you might think. Someone who grew up using expletives and profanity might struggle at first learning how to speak without them, but once they’ve got the habit they’ll find it’s easy to speak without swears. Most of the time it’s like singing; flat notes don’t take more breath to hold than being on key. Certainly it’s equally easy to hear a note whether it’s sharp or correct, other than the twitch a singer makes at wanting it sung better. If people think you’re singing off-key and this surprises you, there’s a skill you don’t have.

Cultivate the skill of honesty. But if you’re socially graceless, I disagree it’s a virtue.

I think it’s a skill issue.

In my defense, I learned to program by using the PRGM button on a TI-83 calculator and experimenting with the fixed list of commands to find out what they did via trial and error. This was not an environment conducive to good programming practice.

Call it intelligence, call it test taking ability, call it expensive tutors, call it whatever you want it’s still there. This is Berkson’s Paradox.

Discuss