Published on October 13, 2025 4:00 PM GMT

re: The Future of AI is Already Written

The essay makes two claims: firstly, that technology determines societal outcomes, and secondly, that the default world after high degrees of automation will be very good. The first has an extensive argument, while the second is a paragraph and a half of possibilities that provides no evidence or argument, so I will focus on the first.

I’m writing this because, compared to most, I’m a technodeterminist. I think that the nature of a society can be substantially predicted from the mode of economic production. While “technodeterminism” is a term of abuse in STS circles, it’s also obviously correct, at least as define…

Published on October 13, 2025 4:00 PM GMT

re: The Future of AI is Already Written

The essay makes two claims: firstly, that technology determines societal outcomes, and secondly, that the default world after high degrees of automation will be very good. The first has an extensive argument, while the second is a paragraph and a half of possibilities that provides no evidence or argument, so I will focus on the first.

I’m writing this because, compared to most, I’m a technodeterminist. I think that the nature of a society can be substantially predicted from the mode of economic production. While “technodeterminism” is a term of abuse in STS circles, it’s also obviously correct, at least as defined. It matters whether you grow rice (needs irrigation funded and controlled by a larger group, and coordination of when you drain your fields) or wheat (more suitable for family farms), as studies have shown (including quasi-experimental work). Both of those are practically identical compared to the difference between plow cultures and hoe cultures, the latter of which put minimal value on physical strength and enable women to do much more economically valuable work, creating less patriarchal societies.

It matters whether you have abundant natural resources, which tilt governance towards control over the resources rather than good treatment of individuals (usually called the resource curse). The impact of guns is typically overstated (the crossbow is actually pretty comparable to the early musket), but guns → democratization is at the very least a credible theory.

My technodeterminism is exactly why I’m concerned about the impact of AI. If you run through the world where governments don’t depend on their citizens for economically valuable labor, it does not follow that those citizens have great lives. You’d have to believe, really strongly, in the kindness of rulers or the power of a populace that is, by definition, not doing economically valuable work. Neither is a good bet.

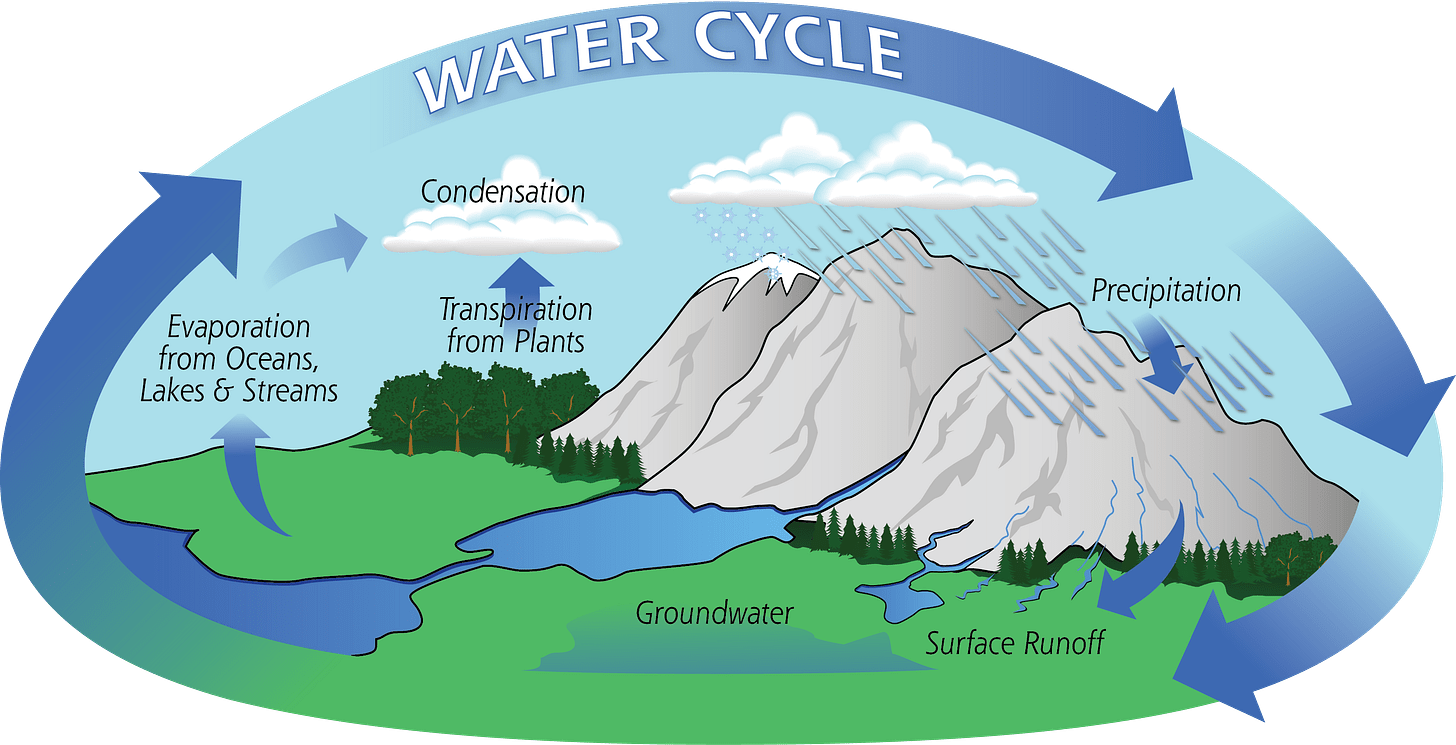

But I committed to an explanation of how my technodeterminism differs from theirs, which returns to the metaphor of water. Barnet, Besiroglu, and Erdil use the metaphor of water running to a valley.

Rather than being like a ship captain, humanity is more like a roaring stream flowing into a valley, following the path of least resistance. People may try to steer the stream by putting barriers in the way, banning certain technologies, aggressively pursuing others, yet these actions will only delay the inevitable, not prevent us from reaching the valley floor.

It’s not, here, excessively pedantic here to point out that not all water is in the Mariana trench. Nor is it even all on the ocean. There is water in clouds. There is water in lakes and glaciers, in some cases miles above sea-level. And yes, in theory all the water “should” follow the path of least resistance to the lowest possible point. And yet there are a few things standing in the way.

People do not always follow the path of least resistance. In the worst days of feudalism, when the rich could do as they willed and the poor suffered what they must, a certain Francis of Assisi gave all he had to the poor. He did not give a small token at feasts, or even 10%: he gave all he had. The water can rise out of the depths, even to the very heavens. We need not follow our incentives to our graves.

The modern era is one of human capital and democracy, as I have said. Yet the last king is not yet dead and buried, nor is he even a representative of the last monarchy, nor is it even obvious that he will not have successors, nor is he stripped of all power. I am thinking of Vajiralongkorn Boromchakrayadisorn Santatiwong Thewetthamrongsuboribal Abhikkunupakornmahitaladulyadej Bhumibolnaretwarangkun Kittisirisombunsawangwat Boromkhattiyarajakumarn, better known as Rama X, King of Thailand, whom it is still illegal in Thailand to insult. Water will generally flow down the mountain and towards the valley, but flowing towards a valley is different from being there already.

The Amish still exist, despite all the pressures and incentives of the modern world. In an era of feudalism, less efficient societies would be conquered. But even if water will eventually run downhill, it can be frozen for years or centuries, and outwait the current trend. There is ice that has remained frozen for over a million years, and the Trump Administration is currently on a quixotic campaign against wind and solar: a society can stand still, even in the face of incentives, for a little while.

So, I shall grant myself the point that we can influence the motion of the ocean, even if we can’t stop it. And if all you or I can do is stand athwart history yelling stop, slowing down the brave new world, there is dignity and honor in such a doomed fight, if it preserves a better world for but one day more. In the long run we are all dead: what will make a better world today and tomorrow?

But our agency is not so circumscribed. America was going to eventually be independent of Britain’s Parliament, just as India and Canada and Australia would be: the costs of administering a far-flung empire were too high, and Britain too small, for it to last forever.1 But America won its freedom rapidly. Canada and Australia had a slow and stately withdrawal of real power vested in the monarch. India saw millions displaced, with hundreds of thousands dead. You can say that those were all paths to the same end, but India today has border disputes with two nuclear-armed neighbors, Australia and Canada are doing well for themselves, and America is the most powerful nation on the planet, with freedom of speech still protected more strongly than anywhere comparable, because that was a priority in the 1780s.

The path these nations took towards independence mattered. The path we take towards a highly automated future will matter. In economics we call this path-dependency, and it rules a tremendous amount around you. There are people trying to make it go well, and none of them think we’re really ready for what will come.2

It is not free to slow the progress that will come: I care about the children who will die. I’m scared of a world where we don’t build AI, and something terrible happens that could have been prevented. I don’t want to unilaterally stop American AI progress. Ultimately I think we have decent odds on a good future. I expect a great deal of futile fights as, to pick an example, the Teamsters try to stop self-driving cars that will save millions of lives, and those efforts will be measured in those killed by the delay more than anything else. That fight will look simple and quick compared to the defense the AMA will put up to keep work in the hands of doctors and out of reach for nurses and assistants. We need to accelerate getting advanced tech into the hands of everyone in the world, and I focus on lifesaving tech like self-driving cars.

The way we get there matters, and it matters more the longer and more important you think the AI age will be. It will go better if AI is under the control of liberal democracies with fully free and fair elections3 that understand what is coming. Those liberal democracies will do better if they pass wise laws that focus on critical risks and don’t listen to rent-seeking guilds. Cyberattacks that wreck moderately important infrastructure4, engineered plagues that kill billions: these are real and clear problems.

If we are to be people of integrity, we should not pretend that we are innocent agents of gravity, doing only what is inevitable. Speeding up means that society has less time to adapt, to plan, and to prepare. It increases every risk associated with the impending transition. Perhaps that is worth it. Barnet, Besiroglu, and Erdil should actually make that case with more than a token fantasy, not pretend that they’re helplessly caught in the current.

My British husband would be quick to emphasize that the specific trigger that really lost them the empire was bleeding it white to beat the Nazis, and there is truth there. But the empire was doomed.

Some will argue that the only way forward is through, and that our planning and preparation will be useless. I can respect that point of view. But nobody who thinks that AGI is coming thinks that voters are prepared for it.

If a small eastern European state had free advertising, in the form of a PSA, at airports in which a cabinet official named the opposition party as the source of a problem, I would say that such a state clearly didn’t have “fully free and fair elections”. By the same logic, America will not have fully free and fair elections in 2026. That line has already been crossed. But much remains to be seen, including the honor and courage of Republican elites (in the face of what I want to acknowledge are terrifying facts about a president who will instruct his AG to go after his enemies, remove law enforcement protection from them, and call them “fascists” to his followers). Currently, I think the odds are much better on restoring America to the group of countries with fully free and fair elections than trying to enable AI progress in countries with fully free and fair elections. And I confess I am a patriot, which may be biasing my thinking.

The critical infrastructure is generally well-protected, and to the extent that AI lowers the costs of cyberattacks I expect more of the problem to be an expanding target range.

Discuss