From Text to Token: How Tokenization Pipelines Work

By James Blackwood-Sewell on October 10, 2025

When you type a sentence into a search box, it’s easy to imagine the search engine seeing the same thing you do. In reality, search engines (or search databases) don’t store blobs of text, and they don’t store sentences. They don’t even store words in the way …

From Text to Token: How Tokenization Pipelines Work

By James Blackwood-Sewell on October 10, 2025

When you type a sentence into a search box, it’s easy to imagine the search engine seeing the same thing you do. In reality, search engines (or search databases) don’t store blobs of text, and they don’t store sentences. They don’t even store words in the way we think of them. They dismantle input text (both indexed and query), scrub it clean, and reassemble it into something slightly more abstract and far more useful: tokens. These tokens are what you search with, and what is stored in your inverted indexes to search over.

Let’s slow down and watch that pipeline in action, pausing at each stage to see how language is broken apart and remade, and how that affects results.

We’ll use a twist on “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” as our test case. It has everything that makes tokenization interesting: capitalization, punctuation, an accent, and words that change as they move through the pipeline. By the end, it’ll look different, but be perfectly prepared for search.

The full-text database jumped over the lazy café dog

Filtering Text With Case and Character Folding

Before we even think about breaking our text down we need to think about filtering out anything which isn’t useful. This usually means auditing the characters which make up our text string: transforming all letters to lower-case, and if we know we might have them folding any diacritics (like in résumé, façade, or Noël) to their base letter.

This step ensures that characters are normalized and consistent before tokenization begins. Café becomes cafe, and résumé becomes resume, allowing searches to match regardless of accents. Lowercasing ensures that database matches Database, though it can introduce quirks: like matching Olive (the name) with olive (the snack). Most systems accept this trade-off: false positives are better than missed results. Code search is a notable exception, since it often needs to preserve symbols and respect casing like camelCase or PascalCase.

Let’s take a look at how our input string is transformed. We are replacing the capital T with a lower-case one, and also folding the é to an e. Nothing too surprising here. All of these boxes are interactive, so feel free to put in your own sentences to see the results.

↓

lowercase & fold diacritics

the full-text database jumped over the lazy cafe dog

Of course, there are many more filters that can be applied here, but for the sake of brevity, let’s move on.

Splitting Text Into Searchable Pieces with Tokenization

The tokenization phase takes our filtered text and splits it up into indexable units. This is where we move from dealing with a sentence as a single unit to treating it as a collection of discrete, searchable parts called tokens.

The most common approach for English text is simple whitespace and punctuation tokenization: split on spaces and marks, and you’ve got tokens. But even this basic step has nuances: tabs, line breaks, or hyphenated words like full-text can all behave differently. Each system has its quirks, the default Lucene tokenizer turns it’s into [it's], while the Tantivy splits into [it, s]1.

Generally speaking there are three classes of tokenizers:

Word oriented tokenizers break text into individual words at word boundaries. This includes simple whitespace tokenizers that split on spaces, as well as more sophisticated language-aware tokenizers that understand non-English character sets2 . These work well for most search applications where you want to match whole words. 1.

Partial Word Tokenizers split words into smaller fragments, useful for matching parts of words or handling compound terms. N-gram tokenizers create overlapping character sequences, while edge n-gram tokenizers focus on prefixes or suffixes. These are powerful for autocomplete features and fuzzy matching but can create noise in search results. 1.

Structured Text Tokenizers are designed for specific data formats like URLs, email addresses, file paths, or structured data. They preserve meaningful delimiters and handle domain-specific patterns that would be mangled by general-purpose tokenizers. These can be essential when your content contains non-prose text that needs special handling.

For our example we will be using a simple tokenizer, but you can also toggle to a trigram (an n-gram with a length of 3) tokenizer below to get a feel for how different the output would be (don’t forget you can change the text in the top box to play round).

↓

split on whitespace and punctuation

thefulltextdatabasejumpedoverthelazycafedog

10 tokens

Throwing Out Filler With Stopwords

Some words carry little weight. They appear everywhere, diluting meaning: “the”, “and”, “of”, “are”. These are stopwords. Search engines often throw them out entirely3, betting that what remains will carry more signal.

This is not without risk. In The Who, “the” matters. That’s why stopword lists are usually configurable4 and not universal. In systems which support BM25 they are often left out altogether because the ranking formula gives less weight to very common terms, but in systems which don’t support BM25 (like Postgres tsvector) stopwords are critically important.

↓

remove stop words

fulltextdatabasejumpedoverlazycafedog

8 tokens

Notice how removing stopwords immediately makes our token list more focused? We’ve gone from ten tokens to eight, and what remains carries more semantic weight.

Cutting Down to the Root with Stemming

Jump, jumps, jumped, jumping. Humans see the connection instantly. Computers don’t, unless we give them a way5.

Enter stemming. A stemmer is a rule-based machine that chops words down to a common core. Sometimes this happens elegantly, and sometimes it happens brutally. The foundation for most modern English stemming comes from Martin Porter’s 1980 algorithm, which defined the approach that gave search engines consistent rules for stripping suffixes while respecting word structure. Today many stemmers are based on the Snowball variant.

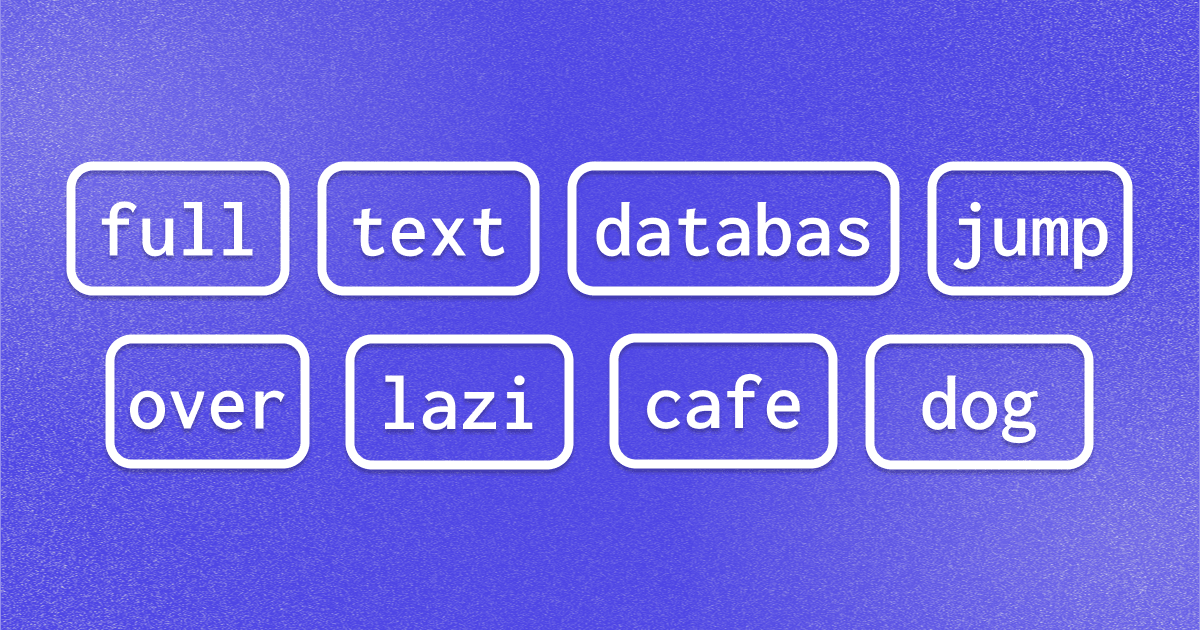

The results can look odd. Database becomes databas, lazy becomes lazi. But that’s okay because stemmers don’t care about aesthetics, they care about consistency. If every form of lazy collapses to lazi, the search engine can treat them as one6. There’s also lemmatization, which uses linguistic knowledge to convert words to their dictionary forms, but it’s more complex and computationally expensive than stemming’s “good enough” approach7.

↓

porter stemming

fulltextdatabasjumpoverlazicafedog

8 tokens

Here’s the final transformation: our tokens have been reduced to their essential stems. Jumped becomes jump, lazy becomes lazi, and database becomes databas. These stems might not look like real words, but they serve a crucial purpose: they’re consistent. Whether someone searches for jumping, jumped, or jumps, they’ll all reduce to jump and match our indexed content. This is the power of stemming: bridging the gap between the many ways humans express the same concept.

The Final Tokens

Our sentence has traveled through the complete pipeline. What started as “The full-text database jumped over the lazy café dog” has been transformed through each stage: stripped of punctuation and capitalization, split into individual words, filtered of common stopwords, and finally reduced to stems.

The result is a clean set of eight tokens:

fulltextdatabasjumpoverlazicafedog

This transformation is applied to any data we store in our inverted index, and also to our queries. When someone searches for “databases are jumping,” that query gets tokenized: lowercased, split, stopwords removed, and stemmed. It becomes databas and jump, which will match our indexed content perfectly.

Why Tokenization Matters

Tokenization doesn’t get the glory. Nobody brags about their stopword filter at conferences. But it’s the quiet engine of search. Without it, dogs wouldn’t match dog, and jumping wouldn’t find jump.

Every search engine invests heavily here because everything else (scoring, ranking, relevance) depends on getting tokens right. It’s not glamorous, but it’s precise, and when you get this part right, everything else in search works better.

Get started with ParadeDB and see how modern search databases handle tokenization for you.

Footnotes

Which is better? That depends: it's seems more correct and skips storing a useless s token, but it wouldn’t match on a search for it. ↩

1.

General purpose morphological libraries like Jieba and Lindera are often used to provide tokenizers that can deal with Chinese, Korean, Japanese and characters. ↩ 1.

When we remove stopwords we still keep the original position of each token in the document. This allows positional queries (“find cat within five words of dog” even though we have discarded words. ↩

1.

Lucene and Tantivy both have stopwords off by default, and when enabled for English they use the same default list: [a, an, and, are, as, at, be, but, by, for, if, in,into, is, it, no, not, of, on, or, such, that, the, their, then, there, these, they, this, to, was, will, with] ↩

1.

Another method is vector search, which trades lexical stemming for searching over semantic meaning. ↩ 1.

Words can also be overstemmed, consider university and universe which both stem to univers, but have very different meanings. ↩

1.

Lemmatization uses actual word lists to make sure it only makes real words. To do this it accurately it needs to know the “part of speech” the source word is (noun, verb, etc..). ↩