I launched the Every 5x5 Nonogram web game about five months ago. It was a collaborative web game with the preposterous goal of solving all 24,976,511 5x5 solvable nonogram puzzles.

As the game nears a close, I thought it would be a good time to reflect on the project and share my experience making it, the decisions I made, and the problems I encountered. There is a lot to cover, so I’m splitting it into three parts, one released each week.

Part 1: Idea, Architecture, & Launch

Part 2: Scaling, Bots, & Bugs

Part 3: Reception & Lessons Learned

The idea

I created a nonogram puzzle game for iOS over 16 years ago, Pixelogic, which I still maintain t…

I launched the Every 5x5 Nonogram web game about five months ago. It was a collaborative web game with the preposterous goal of solving all 24,976,511 5x5 solvable nonogram puzzles.

As the game nears a close, I thought it would be a good time to reflect on the project and share my experience making it, the decisions I made, and the problems I encountered. There is a lot to cover, so I’m splitting it into three parts, one released each week.

Part 1: Idea, Architecture, & Launch

Part 2: Scaling, Bots, & Bugs

Part 3: Reception & Lessons Learned

The idea

I created a nonogram puzzle game for iOS over 16 years ago, Pixelogic, which I still maintain to this day. I created a newsletter, Pixelogic Weekly, share Pixelogic’s daily and weekly puzzles along with deep dives on nonogram-related topics as a way to reach a new audience. I was curious about how many nonograms there were, so I ran my Pixelogic nonogram solver on all possible 5x5 grids. After a couple hours of running through all 33,554,432 grids the answer came back: 24,976,511.

Well, this gave me a newsletter topic for Pixelogic Weekly #7, but it also made me wonder: what do all 25 million of these puzzles look like? I wanted to create a giant static website to just browse them. But what if you could also play the puzzles? Well, that’s a lot for one person. What if everyone could collaborate and work together towards solving them?

I was then reminded of One Million Checkboxes, a collaborative, realtime game where internet strangers worked together to check every checkbox. The idea clicked: I would also create a collaborative game with the goal to solve all 25 million puzzles. I started building it on Memorial Day and launched it 4 days later.

Tech stack

I wanted to build the game fast, so I thought about what I could reuse. Pixelogic, my nonogram game, is written in Flutter, so I thought about creating this game as a Flutter web app, reusing some components from my Pixelogic game. I decided against this though, as I remembered that Flutter web framework required a payload size of at least of few megabytes of JS, and I wanted something a bit leaner. I decided instead to model it after the Pixelogic website daily puzzle player. I didn’t end up reusing as much of the code as I thought, it gave me a good scaffolding to bootstrap the project.

Here is a breakdown of the various components of the stack:

Firebase Hosting: hosts the pixelogic.app website

Eleventy: generates most of the static webpages on the site, including the scaffolding around the Every 5x5 Nonogram game

Lit: the UI was written as web components using Typescript, bundled with Rollup.

Firebase Functions: interface to the backend to perform actions such as marking a puzzle as solved - where additional validation is needed.

Cloud Storage: all ~25 million nonogram grids and their solutions are split up into thousands of text files hosted directly from Cloud Storage.

Firebase Realtime Database: this was the real workhorse of the game. The RTDB was responsible for keeping track of which puzzles were solved, updating all connected clients to the solved puzzle solutions, solved counts, and presence markers.

You probably will notice things have a Google slant. I’m a former Googler and it shows here.

An infinite list

For the frontend, the central piece was the Lit virtualizer web component which powered the enormous grid of puzzles. The virtualizer component only renders elements that are visible in the viewport while giving the appearance of a continuous page, reducing memory usage and improving performance. Initially I wanted all puzzles on a single page, though quickly realized that exceeded the limits of the Lit virtualizer component and the exceeded the max page height supported by some browsers (test your browser’s max page height here).

So I decided to spit up the puzzles into 1,000 sections. Each section was rendered as a separate page, and would contain approximately 25,000 puzzles. The virtual list component seemed to handle that number much better, and had the added benefit of providing smaller milestones while everyone worked towards the larger goal.

Storing puzzles

Now that I had the frontend structure in place, I needed a way to store and retrieve the 25 million puzzles. Even with the puzzles split into 1,000 sections, 25k puzzles was too many puzzles to retrieve at once. I split each section into 1,000 segments, containing 250 puzzles each. This was a good number, as it was just a bit more puzzles than you could see on the page at one time with a large monitor.

To store the puzzles, I decided to keep it simple and store the puzzles for each segment as a text file, each line of which was a base64 representation of the puzzle. These puzzle files would be stored on Cloud Storage, which was much more cost efficient than storing it in a database behind an API layer.

My first pass at storing the puzzles was to do what I do in Pixelogic: convert the solution grid into a binary array (1=filled square, 0=empty square), then convert that into a base64 string. So a 5x5 nonogram would be stored as a 25-bit number that has a base64 representation that looks like “fsTDAA==” for example. This type of representation may work fine for my native apps, though for this web game I was worried it would make abuse that much easier. Since the markPuzzleSolved endpoint requires passing a solution grid, this makes it fairly trivial to scrape the puzzle solutions and just pass them to the endpoint. Instead I wanted to encode the row and column clues, not the solution grid directly. I thought this would mitigate bots (it didn’t).

The most trivial way to encode the clues would just be to create an array of ints where each array element is a clue number with some delimiter to separate each row and column. Even if you base64 encode, this results in a much longer string than the base64 encoded solution grid, and I was wary of my potential bandwidth costs. Then I realized that each row and column had only 13 possible configurations (for a 5x5 puzzle): [0], [1], [1, 1], [1, 1, 1], [1, 2], [1, 3], [2], [2, 1], [2, 2], [3], [3, 1], [4], [5]. I assigned a number (0-12) to each of this possible states, which can fit in 4-bits. When accounting for 5 rows, and 5 columns, you can represent this in 4x10=40 bits. Not quite as compact as the 25-bit solution, though after base64 encoding it you still get an 8 character string (ex. “GCIZcGI=”), same as the solution method. See example clues file.

Solving in real-time

Players needed to be able to solve a puzzle and have the solution reflected in all other players viewing that same puzzle in real-time. Since I was using Firebase, Realtime Database, which works by opening Web Sockets to each client pushing updates as they’re made, was the clear choice to support this feature.

Initially I planned to have every individual grid square sync across clients in real-time as players toggle them on or off. Unfortunately, this would incur a much server load as each individual time selection would need to be updated on the server then propagated to all clients. There was also the possibility (rather, inevitability) of abuse, where players could “draw” anything they liked across the grids. I decided to only sync the grids when they were correctly solved.

Here’s the sequence of events at a high level:

Player visits segment X. 1.

Client downloads segment X’s clue file from Cloud Storage, renders puzzle boards. 1.

Client listens to Realtime Database (RTDB) path associated with solutions of solved puzzles in this segment (/segments/X/solved_grids). As the RTDB updates the data at this path, the UI is updated to reveal solutions for solved puzzles. 1.

After player solves puzzle Y, client calls Cloud Function with puzzle number (Y) and base64 solution grid as parameters. 1.

Cloud Function verifies solution against non-public list of puzzle solutions (also stored in Cloud Storage). If solution matches, the RTDB path (/segments/X/solved_grids) is updated to include the solution to puzzle Y. This update propagates to all clients listening to segment X. 1.

A RTDB trigger listening to /segment/<segment_num>/solved_grids triggers, which then updates other RTDB values, such as total solved count and section progress (which in turn updates clients listening to these values).

Presence

Realtime experiences, whether its One Million Checkboxes or a Google Doc, use cursors so you know where others are around and what they’re doing.

When a player visits they are assigned an anonymous account ID via Firebase Auth. 1.

When a puzzle is clicked in segment X, the client updates RTDB path /presence/users/<accountID> with the puzzle number and timestamp. The RTDB access rules prevents anyone other than the player with the matching anonymous account ID to write to this path. 1.

A RTDB trigger listening to /presence/users/ is invoked, updates segment-level presence paths (/presence/segments/X) which stores a list of Presence IDs* of players that are currently on that segment. 1.

Players listening to presence updates for segment X will receive the updated presence IDs and puzzle numbers, and will update the colored borders.

*Presence IDs are the account ID hashed to the values 0-100, each of which is mapped to a unique color. This way the account IDs of other players can remain private while still allowing nearby players to have unique, stable identifying colors.

Launch

On Friday May 30 around noon, after 4 days of hacking the game together, I decide its time to launch. Could the game have benefited from an extra day or two or even a week of extra development time before launch? Sure. But I was motivated to launch sooner than later; I was going on a long vacation the next weekend, so I wanted at least a week to fix any problems before I left.

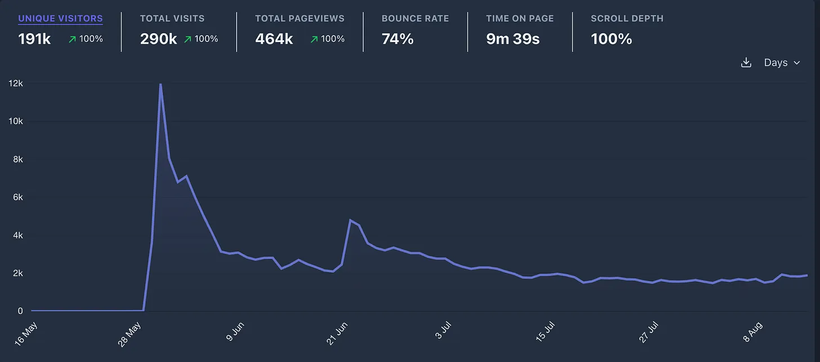

I deployed it to my production web server, posted it on my Bluesky and Mastodon accounts and a few nonogram-related subreddits and waited. To my surprise, the total online numbers started to climb and climb fast. In the first half day, 4k visitors tried the game. On the second day, Nolen, the developer behind One Million Checkboxes, posted my game to Hacker News. Visitors that day climbed to 12k, with nearly 1,500 simultaneous players.

It was a (sort of) viral hit! Or at least, as close to one as I’ve ever gotten. Also, things ran almost without a hitch; the site seemed to keep up with the traffic. I gotten pretty lucky here as I only tested with myself, my wife and daughter before the launch.

Then the bots came...

Stay tuned for next week, when I’ll share part 2: Scaling, Bots, & Bugs!

Joel