Gina Gagliano | November 3, 2025

*Mariko Tamaki burst onto the comics scene in 2008 with the graphic novel Skim, created in collaboration with her cousin Jillian Tamaki. *

Since then, she’s been busy.

*She and Jillian have created many more amazing graphic novels – and she’s also written superhero comics including She-Hulk, Supergirl, and Batman, written graphic novels with award-winning authors Steve Rolston and Rosemary Valero-O’Connell, and written a number of YA novels that range from contemporary coming-out stories to mysteries (including a contemporary Anne of Green Gables retelling). *

*In this interv…

Gina Gagliano | November 3, 2025

*Mariko Tamaki burst onto the comics scene in 2008 with the graphic novel Skim, created in collaboration with her cousin Jillian Tamaki. *

Since then, she’s been busy.

*She and Jillian have created many more amazing graphic novels – and she’s also written superhero comics including She-Hulk, Supergirl, and Batman, written graphic novels with award-winning authors Steve Rolston and Rosemary Valero-O’Connell, and written a number of YA novels that range from contemporary coming-out stories to mysteries (including a contemporary Anne of Green Gables retelling). *

In this interview, Mariko Tamaki spoke to me about superheroes, queer identity, and her new murder mystery graphic novel with Nicole Goux, This Place Kills Me.

Mariko Tamaki

Mariko Tamaki

Gina Gagliano: You have a new book! Congratulations!

Mariko Tamaki: Thank you!

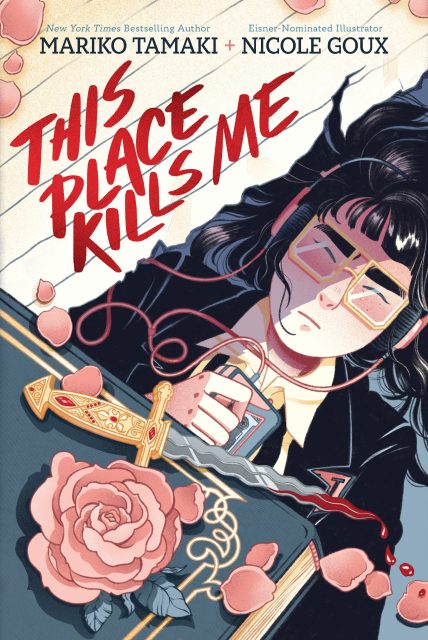

This Place Kills Me is a murder mystery set in the late 80s, at an all-girls private school called Wilburton Academy in a fictional, secluded, northeastern town. It is about a girl named Abby Kita who goes to this school under not-great circumstances that most of the school don’t know about. And she ends up being the first new girl at the school in the history of the school. She’s walking into a room where everybody knows everybody really well, and they’re all kind of the same, and then Abby is this weirdo Asian person in aviator glasses who shows up and nobody likes her. Which is fun, obviously.

cover for This Place Kills Me by Nicole Goux, illustrated by Mariko Tamaki (Abrams, 2025)

cover for This Place Kills Me by Nicole Goux, illustrated by Mariko Tamaki (Abrams, 2025)

And then she goes to the school play one night and ends up talking to the girl who is the star of the play, Elizabeth, and has the first best conversation she’s had since she’s gone to school. Then the next day, she wakes up and she finds out that Elizabeth has been killed, or is murdered . . . is dead, essentially. Everybody says that it’s suicide, and Abby doesn’t believe that. Abby decides to investigate what happened, which of course endears her even more to everybody who already hated her. So, it’s a story of an uphill battle.

It’s great, a really fun and fast and pacey mystery with lots of teen angst dynamics.

Oh, yeah.

One of the key elements of this book is relationships between teachers and students. And it’s not the first time that you’ve written about those kinds of relationships, either. Can you talk a little about what interests you about that sort of dynamic?

I think the dynamic between adults and kids is a part of any story about younger people. You don’t exist with autonomy and complete agency as a younger person, and so adults are a part of your life, and they structure your life, and I think that I always want adults to be a part of their lives, and to be a source of conflict, and a source of support. A lot of the time, they make life more difficult, especially if you’re trying to do something that adults don’t want you to do. So, I think that that’s a part of all my stories. In this particular case, I think there’s a dynamic between the adults and the students that they’re kind of reinforcing each other. Inasmuch as everybody wants to think of themselves as a rebel.

There’s a certain amount of the school that’s set up by the adults as being like, this is what you shouldn’t do, and then reinforced by the students.

I think definitely there’s a lot there in the power dynamic and the authority and looking-up-to-people dynamic, and how that can be good, or be taken advantage of.

Nicole Goux

Nicole Goux

I think I like to also sort of spread out the who’s the bad guy-ness of it all, and that was the thing that Nicole Goux (who illustrated This Place Kills Me) and I talked a lot about, because the killer changed throughout the scripting process.

I think the best outcome as a writer is always ‘everybody made this worse.’ You know, that there was somebody who was the catalyst, but then there’s a domino effect of everybody supporting this bad outcome.

Can you talk about music, which is a big part of this book, too? What inspires you about music and how you included it in this book?

I think in this particular case, music is a very social thing. There’s the kind of music that everybody was listening to, although my experience of private school dorms was that you weren’t really allowed to blast your music with impunity. So for the main character, Abby, music is really her escape. The one place you can go that nobody can touch you is to have your headphones on and to just be listening to your music. For Abby, that is very early REM. Very, very early. So you have to go Google that if you’re a young listener, reader.

But also, part of it is that this book was largely inspired by my youth, and when I was a kid, we used to make mixtapes that had liberal amounts of recorded talk. Like, you’d make yourself an amateur DJ. So you would introduce tracks to your friends? Like, ‘hey, this is your best friend, and this next track is the one that you were listening to last week,’ kind of thing.

I loved the personalization of that, it was the thing I was obsessed with. I had a tape when I was a kid that was a recording of my friend and I at the cottage that I loved, because in addition to having Bootsauce on it, it also had my friend and I just talking at the cottage for an hour, while smoking, and it was amazing. I thought it was the coolest thing in the world, I was like, ‘you can hear us smoking in this!’

That’s amazing.

This isn’t the first time you’ve done a mystery novel. What really interests you and makes you want to keep coming back to that genre?

It’s a huge challenge to write a mystery. A well-structured novel is always hard. Novels are always hard, but I think that plot-wise, mysteries are just fantastically difficult. I felt like this was the natural outcome of my own obsession with murder mysteries and prose, and also working on* Batman Dark Detective* for as long as I did, and also working in television, then getting a handle on plot and these sort of reveals.

I just thought, ‘wow, it would be really hard to do a murder mystery in a graphic novel.’ And that just seemed like a really great challenge. Little did I know that would be a huge challenge; that it would be the hardest thing I’ve ever written. I could not have done it without Nicole. We really wrote this together. She really was the guiding force and the person to say, ‘I think this is really obvious, this doesn’t work’ in the back and forth of the scripting process.

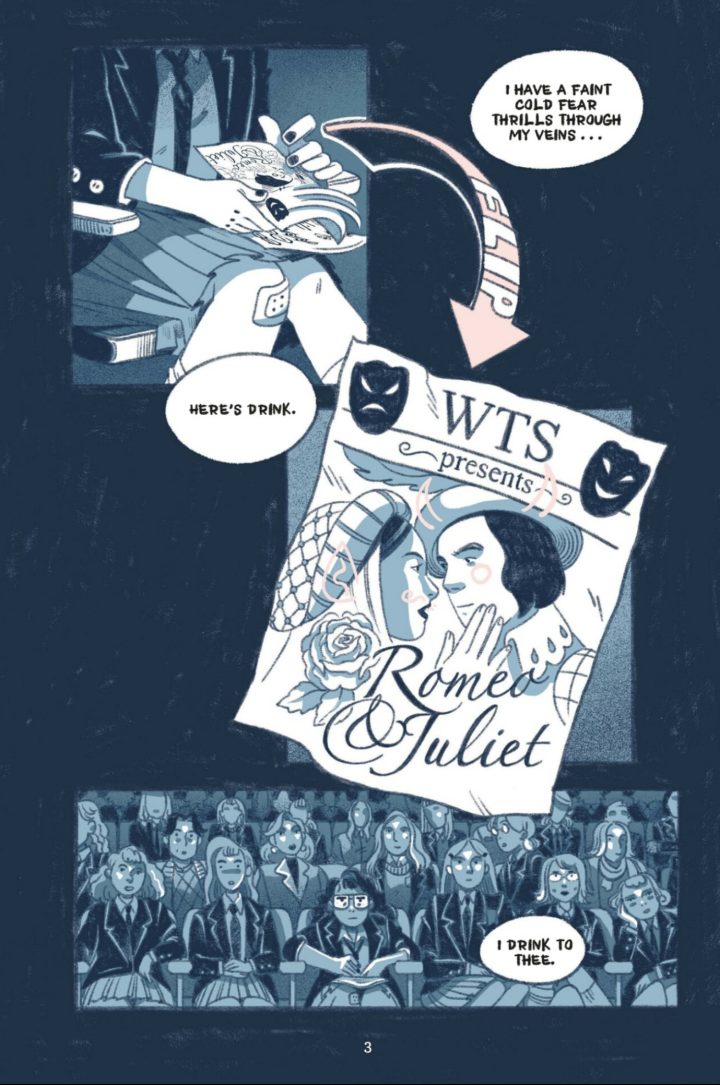

page from This Place Kills Me by Nicole Goux, illustrated by Mariko Tamaki (Abrams, 2025)

page from This Place Kills Me by Nicole Goux, illustrated by Mariko Tamaki (Abrams, 2025)

I think every once in a while, it’s good to sort of let yourself go with what just feels easy, and I definitely have written a lot of books like that. I’m working on a book now that is just so easy, because it just feels very ‘coming from the core of me’ type situation. After you’ve been doing this for a while, it’s good to do something really hard.

Some authors who I’ve heard describe writing murder mysteries as: you start out with a cast of characters, and then you don’t know at the end who’s gonna have committed the murder, and some authors are like, I start from who committed the murder, and then I go back. Do you have an approach in that?

Well, I did in the outline. I always think comic outlines should be burned, because no one should ever see what you originally thought that the book was going to be. And that’s true for almost everything I’ve ever written.

But we had this cast, a lot of whom didn’t show up in the final book. Like, there was a guidance counselor that kind of disappeared. I think we knew the central aggravating force that was going to take place, that was going to be part of the history that was setting up this book.

Then we went back and forth on who the killer would be. It is kind of like Clue, where you’re like, ‘well, Colonel Mustard, nobody’s looking at Colonel Mustard.’ And then you write a Colonel Mustard draft, and you’re like, ‘everybody knows it’s Colonel Mustard!’ And then you’re like,’can we take the Colonel Mustard draft and make it Scarlet?’ In the end, does that work?

As somebody who reads and watches a lot of murder mysteries, it always feels like a weird cop-out when you’re like, ‘oh, you just made it this random person at the last minute.’ Like, that’s not really fair. I’m reading Margaret Miller, who’s this woman who wrote mysteries in the 50s, and she is just a masterclass in ‘you never see it coming.’ It’s right there the whole time, and you never see it coming. To me that is the ideal – to be able to get to that place of being able to bury your killer in a way that they are there the whole time, they’re hanging out, they’re taking you to the zoo, and they seem really nice, and yet all that time. . . . I would love to be able to get to that place.

Are there other mystery authors who you like? I know you said that you love reading in that genre, and I do also.

There are so many. Margaret Miller is my current obsession . . . if you do love the genre, I highly recommend her. She has a bunch of collected books. My favorite story of hers is Beast in View, which I think is her most popular. Also, she’s a Canadian who moved to the States, so I connect up there.

Honestly, I’ve just read a bunch. I really like Karen Slaughter, she’s a really great writer. I really loved* The Thursday Murder Club*, by Richard Oseman, about the people in the retirement home in England that’s about to become a Netflix series. He’s really great, and oh, Liz Moore. Liz Moore is amazing. Her *God in the Woods *is really good.

It’s funny, because now, as I read murder mysteries and I see how tricky they get, I’m like, ‘can you do that in a graphic novel? Can we do that in a graphic novel?’

Theater is also a big element of this book, and I know that you did some spoken word performance. You’re talking about working for TV in this interview. Did that experience affect how you approached the theater element in this book?

One thing you could also say is I put Romeo and Juliet in so many things that I write, because I’m obviously obsessed with that play.

I was not really the most sporty of kids in high school, so theater was the one activity I eventually kind of got into. It kind of creates this very intense, heady group of people. Everybody who’s in a theater troupe in high school is a little bit – you know, it’s an intellectual exercise as well as a sporty exercise, so you all kind of become the Dead Poet Society somehow. I like that element of it. It’s a little cultish.

page from This Place Kills Me by Mariko Tamaki, illustrated by Nicole Goux (Abrams, 2025)

page from This Place Kills Me by Mariko Tamaki, illustrated by Nicole Goux (Abrams, 2025)

But Romeo and Juliet, what is it about that play?

I read it when I was . . . I think we got it when I was in grade ten. And I really loved it. It’s my favorite Shakespeare play. At the same time, it’s a very odd choice to show a bunch of teenagers – a play about two people who fall in love the first day they meet, and then decide that life is not worth living if they can’t be with each other. Or, you know, at least hatch a stupid plan that involves, ‘we’ll sort of pretend to kill ourselves.’ It’s not great, you know? Like, probably there should be some other play that they watch first. I think I’m kind of always amused by people who are so concerned about what media teenagers consume, to then make sure they always read Romeo and Juliet at the height of their emotional instability seems like an odd choice.

Definitely.

Okay, I want to talk about not fitting in, which is a big subject of this book. Can you talk about what inspires you about that subject to write about?

Well, I think every protagonist I’ve ever written is someone who doesn’t fit in, probably because I did not fit in when I was in high school. And it was a source of a lot of stress.

I just didn’t understand. . . . I was like, ‘I have the Benetton top and the Root shoes, am I not doing this right?’ I just, for whatever reason, could never figure out what it was that I was supposed to do that would somehow get me over the hump of ‘nobody likes this girl.’ I just couldn’t figure it out until I stopped caring. You know, I had a lot of horrible things happen to me in my last years of high school, and then I was like, ‘I don’t care.’ And suddenly, as soon as I didn’t care, I had a bunch of friends.

But . . . I think, in terms of this book, the impetus was to create somebody who, while she’s being constantly told that she doesn’t fit in, and that there’s something wrong with her, just refuses to believe that. Somebody who has a certain amount of resilience, that no matter what she’s told, if it doesn’t sync with what she feels is right or true, then she doesn’t believe it.

That’s definitely a step forward for me from Skim. The character in Skim has a really hard time standing up for herself until the very end of the book. And I think Abby, in this book, for better or for worse, would rather be an outsider than pretend to be an insider. And she’s able to really call it out. She is maybe a little smarter than me at sixteen. So she’s able to say, ‘you guys are full of it. You insist that this is true, and at the same time, you’re saying this, so that doesn’t line up for me.’ And I think that as I get older, and my take on YA changes, I think it doesn’t feel to me like it needs to be just a reflection of my own experiences, which is what it was very much when I started. It’s becoming something different as I get older.

That’s great. So, Abby, your protagonist, she’s constantly picked on for being queer throughout the book. And then it turns out her biggest tormentor is queer, too. Can you talk about that dynamic?

I think the thing is that everybody in this book is under a kind of veil of not being able to talk about things. Everybody is under the same pressure to not be the thing that they are. And I think that pressure is a lot. . . . We’ve tried to establish in the beginning the kind of various levels of pressure that these students are under in terms of their parents and in terms of the school and the expectations of them. I think the other thing was to really look at the experience of queerness as it existed back then, which was different. You really couldn’t say what you were. Now we’re so lucky to have this language of the sort of specifics of identity, and back in the day, there was only one word and you weren’t allowed to say it, you know? It was so hard to say it.

And I think about how that affects different people, and about how different people exist within that. I think Abby is kind of a standout in that she comes through a lot of this pressure to be something else, and knowing that she’s not gonna be anything else. I think her tormentor is really hoping that she will be something else. That somehow, magically, for all the things that she is, that that’s not gonna be true, and she’s actually gonna be straight. She’s not gonna love the people that she loves. And I think identity and pressure affect a lot of people in a lot of different ways, not even just about queerness, you know?

I also think that your tormentor in any situation is very rarely all that far away from you, you know what I mean? A lot of my tormentors in high school, when I’ve spoken to them as an adult, were tormented in their own way. You would wish that they wouldn’t have taken it out on me, because I was just hanging out and trying to be nice, and give everybody fruit-flavored certs so they would leave me alone, you know, but . . . what are you gonna do? The past is the past!

I love how Abby finds the school continually terrible, and at the end of the book, the school is like,’ oh yeah, we are terrible,’ and then shuts down. Did you feel very vindicated as you were writing that? You were like, this is justice that’s happening here!

Yeah! And I feel like me talking about this novel is me actually doing a promo for HBO’s Mean Girl Murderers, which is my favorite reality show.

The vindicating part of any [story] about murder, reality program or not, is just to see somebody brought to justice. But overwhelmingly, that doesn’t always happen, right? And as you see these cases, like the one in this book, come out years later, or decades later, you know a lot of the time this doesn’t pan out that the people who are horrible get called out for being horrible. So we wanted to spread it out. The idea is that there are some elements of justice that are sort of served at the end of this, and there are some that are not.

We went back and forth on it, too, about whether or not we would have someone being walked away in handcuffs. But the truth is, a lot of that stuff happens when you don’t see it, you know? A lot of that stuff happens out of your view, so we wanted to keep that feeling like it’s much more about the characters’ friendships that end up surfacing at the end of this. Rather than ‘Detective Abby gets to see someone thrown behind bars’ type situation.

One of the typical murder mystery things that I do like is that they catch the murderer in the end of the novels, usually.

My partner and I watch a lot of old movies, so what we did was, the kind of classic The Thin Man scene, where everybody’s at the table at the end, and it’s like, ‘I’m going to reveal to you who the murderer is.’ It’s a much more personal thing of Abby getting her moment with this person, to say ‘I see you. You don’t have any power over me. And I see what you have done. And everybody here knows what you have done and why.’ So that’s Abby’s justice.

page from This Place Kills Me by Nicole Goux, illustrated by Mariko Tamaki (Abrams, 2025)

page from This Place Kills Me by Nicole Goux, illustrated by Mariko Tamaki (Abrams, 2025)

Can you talk a little about the historical setting? You said this book is set in the 80s, why the past, and how did that work with the story?

As Nicole said, it’s like we set it in the 80s, and then we proceeded to set it in an all-girls private school in the 80s, so we didn’t get to do any of the cool clothes that would actually be 80s clothes. But I do think that Nicole perfectly captured the colors and the sort of vibe of that setting in these pages.

But I wanted to do two things. One was, I do think that for me, a setting that makes sense is not a modern setting, mostly because of social media. I’m looking forward to the next generation of writers that is really going to understand and write about this era of what it means to be a person in a digital age. In a purely digital age, almost, you know?

But that’s not me. I didn’t grow up with it. I don’t know what it’s like to have Snapchat when you’re fifteen. And I really wanted to have the setting be kind of a goldfish bowl. For that, a private school in that era really works well, because you’re all in this secluded spot, nobody can get away. The sort of world of social media that I understand is a world of gossip, but physical gossip and notes and that kind of rumor mill [was what] I really wanted to play with instead.

page from This Place Kills Me by Mariko Tamaki, illustrated by Nicole Goux (Abrams, 2025)

page from This Place Kills Me by Mariko Tamaki, illustrated by Nicole Goux (Abrams, 2025)

The other thing is, in terms of what I have to say about the world of queerness, is a world that has parallels with this world, queers are still trying to be convinced at all times that something that they know is true is not true. You know, like, something about themselves is not true. We’re constantly pushing back against someone trying to tell us our reality is wrong.

To look at what that was like in a different age is worthy, you know? Queer history has a lot to add to the current struggles of queers, like to understand what it was like during the AIDS crisis, to understand what it was like during the age when being gay was still on the DSM. All of those things are things that I’m personally interested in, so that was another reason to set it when we did.

It’s so interesting that Abby’s . . . . it’s not that her queerness is problematized, but that there’s so much bullying, and it’s all around her queer identity. She’s also Asian American, and everyone’s just, like, ‘actually, this other part of your identity is the thing that we’re tormenting you about.’

It’s funny, because I remember when I was in high school, especially in grade school, there was a group of us who were not white. There was never any specificness to it, probably because back then nobody was going to be clear about what not-white we were, you know what I mean? It was like we were the not-white people. Nobody was like, ‘you know, these two people, one of them is Chinese, and one of them is Japanese.’ They’re not the same, you know what I mean? But we were just kind of herded together as a kind of problematic body, and I think that Abby is just kind of a problematic body. She kind of carries herself in this way that’s slightly more masculine, and she has these glasses that aren’t the kinds of glasses that you would wear. She’s not kind of doing the kind of prettying up and the hyper-femininity that can go when you’re wearing a uniform.

Abby from This Place Kills Me by Mariko Tamaki, illustrated by Nicole Goux (Abrams, 2025)

Abby from This Place Kills Me by Mariko Tamaki, illustrated by Nicole Goux (Abrams, 2025)

It’s very unnamed, because nobody was going to say what it was. It’s just like, ‘we don’t like this.’ You know what I mean? There was a lot of discussion when I was in high school and stuff about, like, who had hairy legs. It wasn’t just about hair, it was about race. But there were little things that people would pick on.

When I was a kid, I was deeply aware that I had way bigger eyebrows than anybody else in my school. And I would say to my mom, ‘can’t we just change that?’

My mom was like, ‘those are your eyebrows, they’re the best eyebrows ever.’

And I was like, ‘nobody loves my eyebrows. Nobody. We need to change this, because this is a problem.’

My mom was like, ‘no, it’s fine, just leave it.’

When I was sixteen years old, I was like, ‘wax them.’ I was like, ‘forget this.’

I think that that’s what Abby is, a kind of complicated body.

A lot of your work has been in the YA space. Can you talk about why young adult stories are a match for the kind of stories you want to tell?

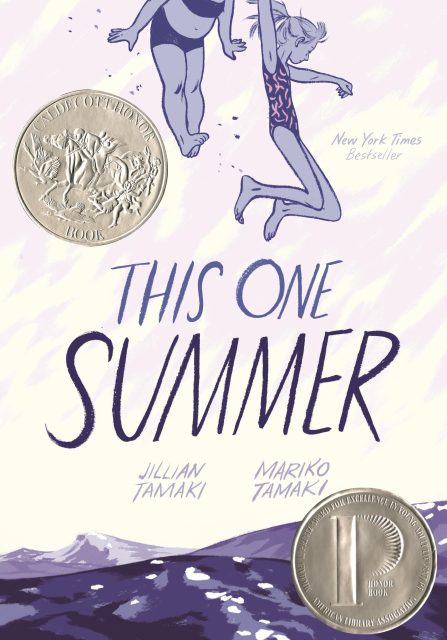

It just kind of happened. Honestly, it wasn’t a thing that I thought out all that deeply. When Jillian and I wrote Skim, we were told it was YA, because somebody was like, ‘well, it’s about teenagers, so it’s YA.’ I think Cecil Castellucci told me that it was YA. I was like, ‘oh, I don’t even know what that is.’ And then when we didThis One Summer, we were sort of still thinking, it’s about kids, but our approach to it was always like, what’s this story? It’s not like we were writing it for kids, we were writing, like, this story.

I don’t have a lot of memories of early childhood, but I have a lot of memories about high school. It’s a thing that I feel, for good or for bad, very closely connected to.

That said, more recently, I’ve felt like I’m ready to move into more adult writing. When Jillian and I did Roaming, it was our attempt to stretch our legs into something that felt like a different realm of experience. I think the next era is writing adult fiction about adults who are obsessed with YA, that’s who the new adult is – I do think it is a different adult. Reading these old books from the 50s and 60s, their take on adults and what adults looked like and sounded like is very different than today.

That young adult period is full of so much change and so many important decisions, it’s hard not to be looking back on that and thinking that is such a central and important time of life.

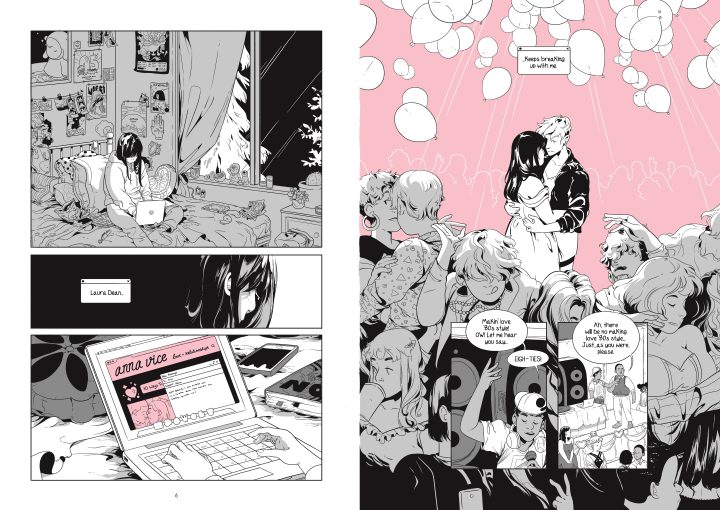

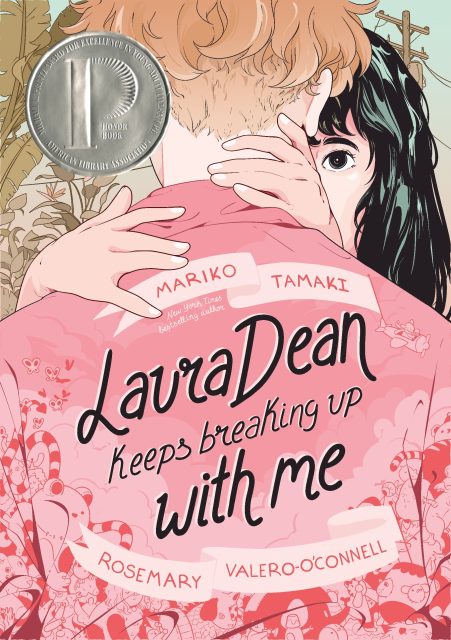

Yeah, and honestly, a lot of that stuff, and also the inclusion of adults in those books, is about being a teenager trying to figure out how to be an adult. I do think even looking at Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me now, your first attempts at relationships are an attempt to kind of get into being older, about trying to be older in those moments with another person.

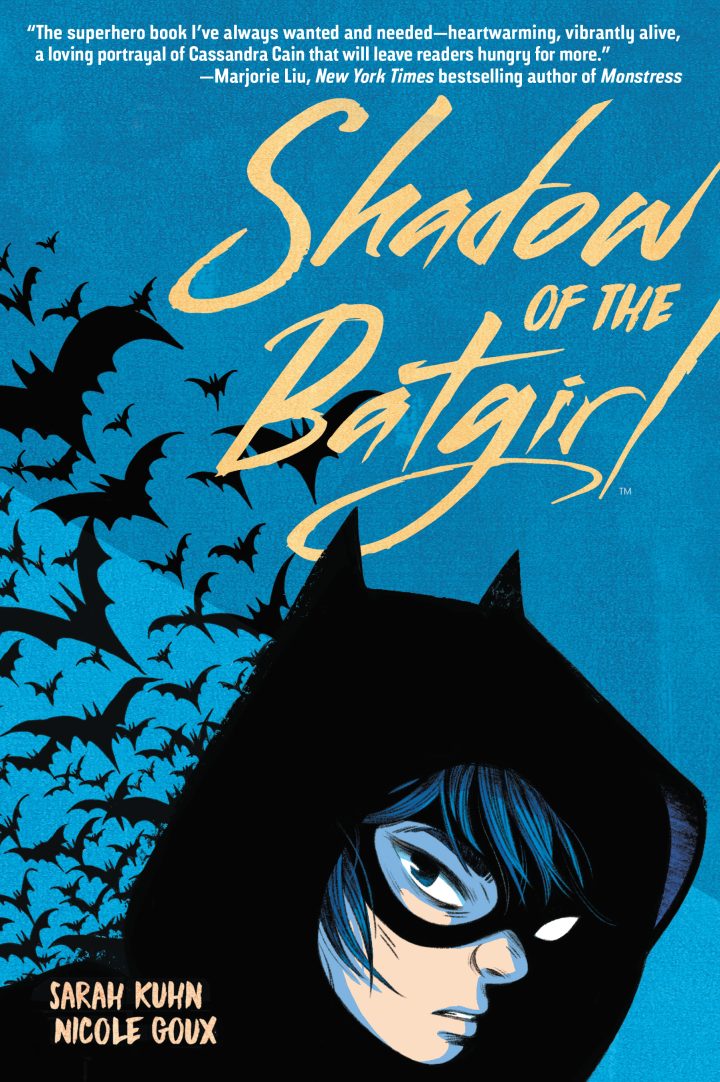

cover for Shadow of the Batgirl by Sarah Kuhn, illustrated by Nicole Goux (DC 2020)

cover for Shadow of the Batgirl by Sarah Kuhn, illustrated by Nicole Goux (DC 2020)

Changing directions a little, can you talk about what it was like to work with Nicole Goux, who is amazing?

I love her. I love her. I mean, I really sought out Nicole for this book. We had a DC Comics dinner, because she had worked on this book, Shadow of the Batgirl, and I had worked on other young DC titles. And I had been looking at her work and reading her work, and I just had this idea, whole hog, that Nicole and I should do a young adult murder mystery.

There is something about her style that is so modern, but also has such a feel to me of those classic illustrated books that I read as a kid, and I just thought, this is perfect. So I went to her and said, ‘look, I’m kind of doing a bunch of things right now, but I would love for you and I to start talking about, if you’re into it, doing a book together, and this is the book I’m thinking of.’ And she was immediately game, and I said to her, ‘okay, I don’t really have time to do anything right now, but I will get back to you, in the next month or so, with a sort of outline of what I think it should be.’ And then the next day, I was like, ‘so I did that outline yesterday. Let’s just get on, let’s just go.’

It came together very quickly. The thing with Nicole is that because she works with her partner, she is very good with a deeply collaborative process, and this was deeply collaborative. We really had to work together because so much is about showing and not showing, and telling and not telling. We had to be 100% on the same page about what was happening in every moment. It was such a detailed approach to writing, and we had to change things all the time. We really went back to the drawing board a couple times when the book had already been started. She’d already started illustrating.

But at no point in the process did I feel like, ‘oh, I don’t think we’ve got it.’ I always felt like we’re close. Then I think when we finally finished the book, we were like, ‘I don’t know if it’s finished. I don’t know, maybe this is done.’ We both had our respective partners read it to, like, reassure us that everything was okay.

She’s such an amazing writer as well. Everybody that I’ve worked with is also a writer in their own right, so I’m always very lucky that they want to work with me when they could just kind of do this themselves. So I really always appreciate that.

You work with all these cool artists, so, so many of them. Is the process of collaboration always the same, or does it change every time? Every book, every different author?

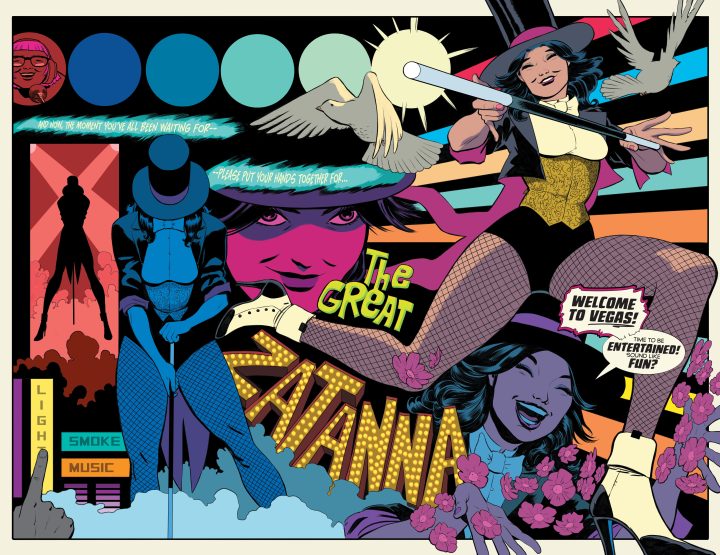

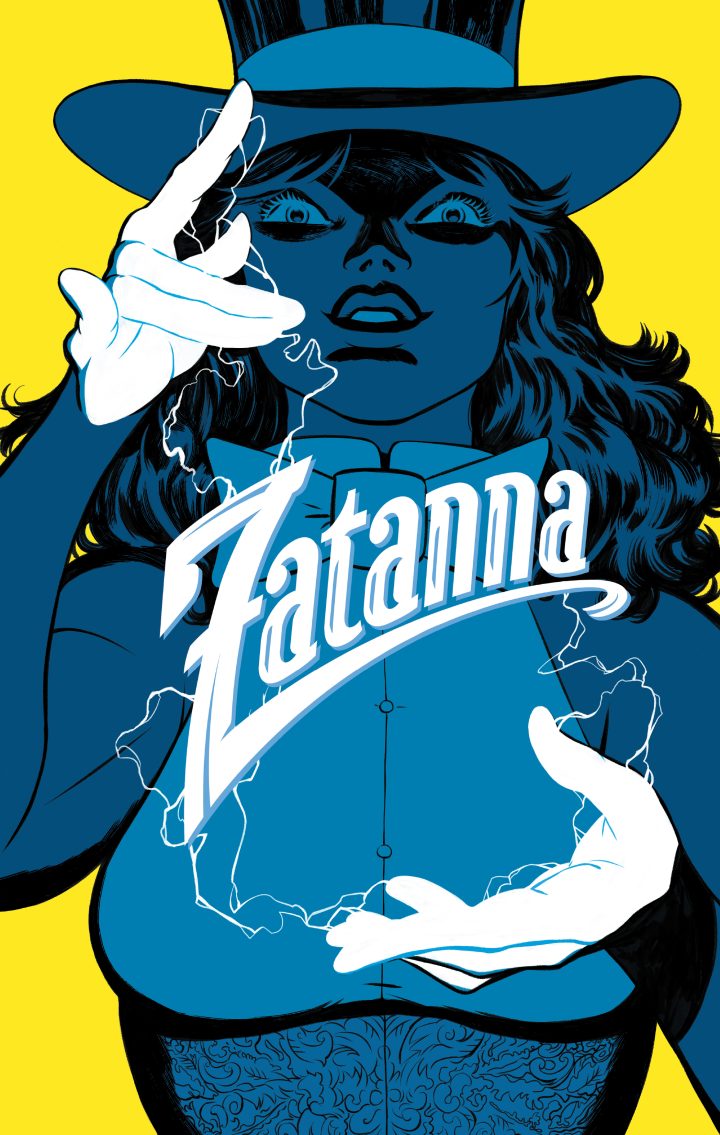

It changes a lot. I think that there is always a thing, though, where they’re all very individual relationships. Even working with Javier Rodriguez on Zatanna. They’re all so different. Also, every editor that you work with brings something to the experience and to the process.

Zatanna art by Javier Rodriguez (DC, 2024)

Zatanna art by Javier Rodriguez (DC, 2024)

There is a moment where I feel like we all click in and we figure out how we’re going to work best together. And usually you have to kind of figure that out, and then once I know what that is, then I feel like I can be a better writer for the illustrator that I’m working with. You know, I feel like with Jillian, we just genetically had that, so that was kind of helpful. But everyone is different, and I always feel like there’s a level of joy on both sides that we’re doing this together.

I found that, too, in television and film, where you just realize, ‘oh, nobody is a burr in anybody’s side here. We’re always just working for the common goal of getting this thing to be what we both want it to be.’ And I think I always approach these things as not what I want it to be, but what we’re going to make it. I don’t think as a writer you can go into things like, ‘this is my book.’ It’s our book. And I think that that helps make it fun, you know? It’s a joy to get together with someone and make a book.

Zatanna art by Javier Rodriguez (DC, 2024)

Zatanna art by Javier Rodriguez (DC, 2024)

But as well as comics, you’ve also written prose where you’re the only person writing. Is there one you prefer? Is the process really different? How does that work, to be switching between the two different formats?

I feel like I write prose because as a writer, I feel like I have to write prose. I really love writing comics. I really love it. I want to keep making sure that I have the muscle to write prose. But there is something about the way comics works that I really like. All of my prose novels end up being half as long as they want them to be, because I just am like, ‘what else do you need to know? It’s all there!’ I just feel like I max out. And I really like working with people. I love working in television, because I love going to a room every day, and getting fed snacks to talk about movies and come up with a plot. I really love the collaborative part of it.

The only thing is, which I guess bleeds into the captions sometimes, is I love describing . . sometimes I will come up with a way of describing a scene that I really love, and I wish I had someplace to put it in a comic. But it doesn’t. So I’ll be like, ‘can we just all acknowledge that this is a really cool way to describe a tree, and then move on?’ You know there’s no place for it, but I think that that’s also partly why I love prose. And also, I think as a prose writer, you can experiment in a way that in comics, the artist is experimenting, or is able to experiment. There’s not as much room for that as the writer of comics.

As well as prose and these graphic novels, you’ve also done a lot of superheroes, some of which also have been in graphic novel form, from She-Hulk to Supergirl. How has that experience been, starting out in very indie comics and ending making these superheroes that have the reputation of being the most commercial part of the industry?

The last San Diego that I went to this year, and hanging out with my DC crew, I was like, ‘I really love this too!’ It’s so much more like you are part of a universe, right? You’re contributing to a universe, and I really like being part of that universe. Editing in a comic book world like DC or Marvel is so different than it is for Abrams or for First Second. They really are experts in the universe, and you’re part of a production. I think getting to be part of that really set me up for writing television. You know, where you are one stage, and there are eight stages after you, so you need to hand us in so we can get everything else going.

I’m ultimately really proud. Some of the work you can see where the struggle was, but I think there are things that I’ve done in superhero comics that I’m really happy are in there. It’s really fun to play with those toys in that sandbox. I’ve worked with Dan Mora, this incredible artist, I’ve gotten to work with Javier Rodriguez and I adore him, he’s so talented, and I think that there are things that we’ve been able to do on the fly with those comics that have been really fun to get to do. I do think that as I’ve gone on, as I’ve gotten more comfortable in it, it’s really felt akin to the work that I do in my own comics. I don’t have complete freedom, but I do think that the restrictions that happen in the stories, like I was recently talking to somebody on a different podcast about Batman, and, you know that Batman can’t kill anybody. Listen: it’s just who he is. But working with that restriction as a writer is fun, and it is sometimes not getting to do what you want, then you get to do something else that surprises you, and I really love that.

Do you have a favorite superhero, either to write about or to read?

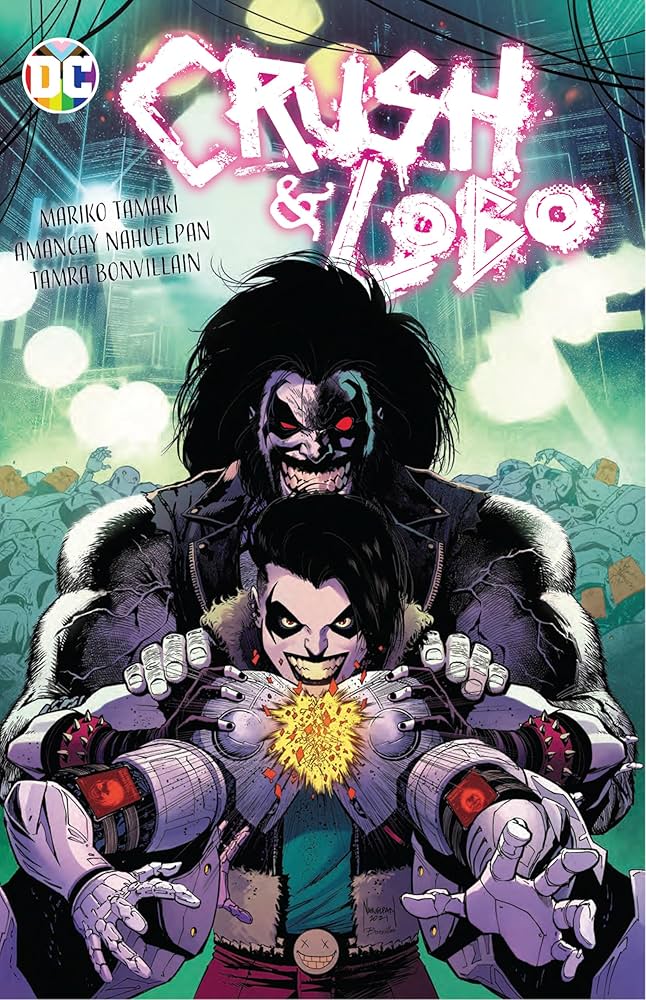

Crush & Lobo by Mariko Tamaki, art by Amancay Nahuelpan (DC, 2022)

Crush & Lobo by Mariko Tamaki, art by Amancay Nahuelpan (DC, 2022)

The work that I’ve done with Andrea Shea is probably my favorite. Working on Zatanna and Crush were my two favorite comics. Working on Crush & Lobo was the most fun I’ve ever had. It was just deliriously silly the whole time. I loved it.

To read . . . my gateway into superhero comics was Hawkeye, Matt Fraction and David Aja’s Hawkeye. The first moment that I read in that comic series, when Hawkeye falls off a building and breaks his leg. I was like, ‘I will read all of these forever.’ I was so enamored with that first moment. I’ve told Fraction this. It just hooked me, for real. I was like, ‘oh, this is what this is.’ That’s why when people say to me, like, ‘oh, I don’t read superhero comics,’ or, ‘I can’t read superhero comics,’ I’m like, ‘you have read the wrong superhero comics, if that is your take on it.’

Tynian’s* The Batman Who Laughs*, all of those things are so fascinating and complex, and, The Flintstones series that Mark Russell and Steve Pugh did . . . parody, it’s such an insight into what’s going on at the moment. And there’s so much amazing parody in superhero comics.

You’ve been writing queer stories since the beginning of your career. Has your approach to that changed at all with the current political climate? It’s been a while since Skim, has your perspective evolved, and has that had anything to do with what’s going on in the world?

Looking back, I really started writing in my queer community in Toronto where my whole audience was queer. I never thought that anybody who was not queer would ever read anything that I wrote. That’s why whenever I’m interacting with fans who have read my Batman stuff. I’m like, ‘the fact that you read my stuff blows me away. I really thought it was gonna be me and the twenty lesbians who are in my writing group for the rest of time, and, like, my mom.’

pages from Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me by Mariko Tamaki, illustrated Rosemary Valero-O’Connell (First Second, 2019)

pages from Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me by Mariko Tamaki, illustrated Rosemary Valero-O’Connell (First Second, 2019)

I think starting from that place, from a world where so much of the writing that I grew up with was so deeply confessional, and was about the immediate experience of queerness, and I just kind of carried that through my career. I’ve never altered from the sort of takes that I had, and I think that that has stayed true.

I sometimes I forget that I’m in the public sphere, and people have reacted to stuff that I’ve done in the DC universe, and I just think, ‘oh, I didn’t think you were gonna read it. I didn’t think you would notice,’ you know what I mean? I thought it was just gonna be us. So, yeah, maybe don’t read it, you know what I mean?

It was a couple friends who explained it to me, they were like, ‘well, they read all of them because they’re fans of the character.’ I’ve had to sort of adjust to that understanding, but I don’t think I’ve adjusted what I do.

cover for This One Summer by Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki (First Second, 2014)

cover for This One Summer by Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki (First Second, 2014)

I feel like sometimes, comics is like, ‘it’s comics, and everyone is queer here,’ and then sometimes it’s like, ‘oh, it’s comics and everyone is reading this.’

Yeah, I do think it’s like that. It has changed so much. Honestly, the first ALA we went to was with Skim, when the number of librarians who said to us, ‘oh, I don’t read comics’ outweighed the number of librarians who were psyched to see us. And from that to This One Summer, which was four years later. It was a whole different world in terms of librarian readership.

And in the indie comic world, the first time Jillian and I went to a comic fair, there were not a lot of women in that space. It was mostly guys selling their comics. And it was all these guys coming up to us saying, ‘what’s this about?’

And we’d say, ‘it’s about a girl in high school,’ and they’d just walk away. Like, immediate no, you know what I mean? And what it’s like now going to TCAF, where if you look around, and you look at who’s making indie comics, and what that looks like – there’s been a turnover. Even if you look at who’s winning Eisners now. That population has changed.

Definitely. In a really good way.

It’s always Gene Yang.

**He won so many Eisners this year. **

Oh my god, I know. I saw him with his little wheelbarrow, trucking them out.

Tell me about what you’re working on now.

So, I am working on a lot of things, most of which aren’t announced yet. This is my year of comics. I have this system, which I will show you, which readers will have to imagine . . . it’s a series of notebooks that I have, so I have a different notebook for each project that I do. And I had to make another one of these folders I keep the notebooks in, because I have so many notebooks that they didn’t all fit in one of them.

Now I have two binders of notebooks of all the projects that are going on. There’s a lot of stuff for DC. This year I wanted to kind of get into doing more stuff. Keep an eye on my Instagram page, because a lot of stuff is about to be announced. I’m trying to expand genres a little bit, so I’m doing something that has a little bit more romance in it. I’m doing something that has a little bit of a historical setting, and doing something middle grade. I’m just trying to kind of keep things moving, and work with new people, and working on the Laura Dean movie, which has been really fun, and really amazing, getting to work with Tommy Dorfman, who’s directing.

So that’s been really great. I had this idea that I would do more books of my own, and then I ended up taking a lot of work with DC, which I’m really enjoying. I’m working with all my favorite editors. I feel like I fell back in love with working with my DC editors. I kind of stalked them at San Diego. I was like, ‘let’s do more of this stuff!’

Do you have any favorite recent graphic novels that you want to talk about?

Oh my gosh. What have I read recently? I’m really loving . . . honestly, this is like a shout-out, it feels like it’s a loop around to me, but I am really loving Sina Grace’s work right now, and I feel so proud of him. I know he’s working on this really personal book right now, about his dog and about Henry. It’s been really amazing to follow him as a writer and artist and see the things that he’s doing.

I’m rereading Allie Brosh all the time, because I’m obsessed with Allie Brosh. I will probably never get sick of reading Allie Brosh. You don’t want to ask your author friends to make more stuff, but honestly and truly, if she would, I would be so happy.

*Portions of this interview have been edited for length and clarity. *