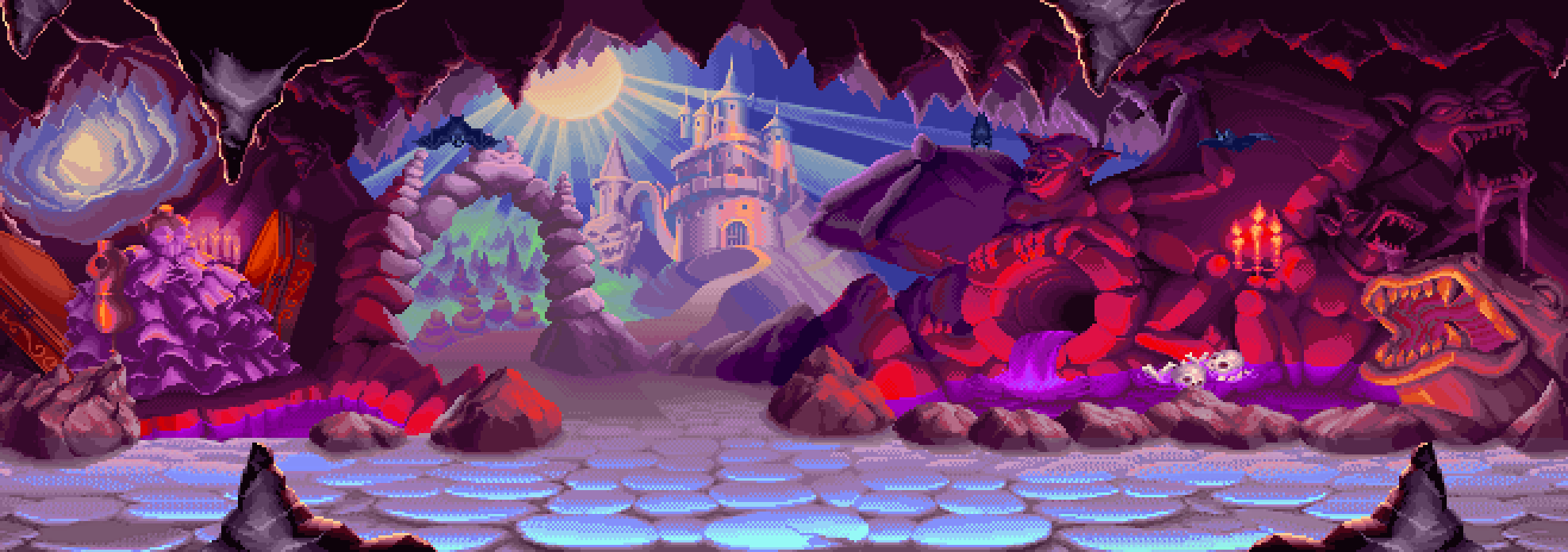

The third and final installment in Capcom’s Darkstalkers series hit arcades in 1997, meaning that the franchise has been dead for nearly thirty years. It’s appropriate, then, that what amounts to “Street Fighter but with vampires and zombies” has not let death slow it down much. All this time later, the fighting ghouls of Darkstalkers continue on — as guests in non-moribund series, in fan culture, and most recently in 2022’s Capcom Fighting Collection, which gave old and new players alike a chance to see this wonderfully weird, horror-themed fighting game in action.

I first encountered Darkstalkers during middle school, when most birthday parties took place in pizza parlors and when most pizza parlors had arcades. Honestly, there could not have been a video game that could have appeal…

The third and final installment in Capcom’s Darkstalkers series hit arcades in 1997, meaning that the franchise has been dead for nearly thirty years. It’s appropriate, then, that what amounts to “Street Fighter but with vampires and zombies” has not let death slow it down much. All this time later, the fighting ghouls of Darkstalkers continue on — as guests in non-moribund series, in fan culture, and most recently in 2022’s Capcom Fighting Collection, which gave old and new players alike a chance to see this wonderfully weird, horror-themed fighting game in action.

I first encountered Darkstalkers during middle school, when most birthday parties took place in pizza parlors and when most pizza parlors had arcades. Honestly, there could not have been a video game that could have appealed more to a twelve-year-old Drew. Darkstalkers had the hard-hitting punch of Street Fighter but also bolder graphics that found the cartoony side of a Frankenstein kicking the crap out of a mummy. It didn’t hurt that it also flashed a cheeky sexuality that you didn’t see so much of in Street Fighter or Mortal Kombat or really any one-on-one fighter that didn’t star Mai Shiranui, and all these years later the Darkstalkers cast still holds a special place in my horror-loving heart.

Given this site’s focus, I couldn’t think of a better way to celebrate Halloween than with an investigation into this series and where its kooky combatants came from — and fortunately I did not have to brave this haunted house alone. No, I had the guidance of Alex Jimenez, the former Capcom staffer who knows these characters intimately and who says the series began with his pitch for a fighting game starring the monsters of the Universal Studios horror canon. Now, this account is somewhat controversial because some in the gaming community claim that Jimenez has fabricated or overplayed his role in the creation of Darkstalkers. What I’m going to attempt to prove in this Halloween post is that elements in the Darkstalkers series would seem to indicate that Jimenez’s claims are true.

At first glance, it might seem nigh impossible that a guy working in Capcom’s California offices would have been able to influence the creation of a Japanese video game to this extent. Having documented video game history for a while now, however, I’ve found the exchange of ideas between Japanese video game companies and their western associates truly did go both ways, even if the predominant perception is that this was not the case. In this piece, I’ll relay Jimenez’s account of how Darkstalkers came to be, and this story begins where many strange collaborative creations do: with Dungeons & Dragons — specifically Dungeons & Dragons: Tower of Doom, Capcom’s side-scrolling beat-’em-up infused with the magic of role-playing games that hit arcades in 1994.

Shadow Over San Mateo

“I got into Capcom in the first place because of that game, because of D&D,” he recalls. “Capcom had licensed Dungeons & Dragons, and they had been trying for about two years to make a D&D game. And [then-publisher] TSR just was not approving any of it.”

Jimenez says that the disconnect resulted from the Capcom team lacking enough experience with the actual tabletop game, their pitches more resembling more Record of Lodoss War than the games that inspired it and other medieval fantasy anime. As a result, a mutual friend recommended Jimenez as a big D&D fan who could consult on the project. Jimenez recalls a meeting during which TSR employee Jim Ward seemed unsatisfied with Capcom’s pitches.

“Jim was about ready to cancel the license because he literally said, ‘Look, you’ve been trying this for two years, and it’s just not working. So maybe we’ll just cut it here and call it a day.’ To this day, I don’t know why, but I was supposed to stay quiet and sit in the back, and instead, I stood up and went, ‘What if we tried this?’ And I laid out an idea for D&D. ‘Like, we’ll have multiple pathways, we’ll branch it, we’ll make it character specific.’ And Jim pounded his fist and said, ‘Yes, that’s D&D. That would work. Can you do that?’”

After the meeting, Jimenez says he felt contrite — “I had broken the cardinal rule of not speaking up when you’re not supposed to, which is a big no-no in Japan” — and went to apologize to then-boss Kazushi Hirao, but Hirao responded with, as Jimenez recalled, something surprising: “What the fuck are you talking about? You saved the project.” And soon Jimenez went to work on ideas for a Dungeons & Dragons video game.

During Jimenez’s time at Capcom, he worked on various games that involved western properties, including Cadillacs and Dinosaurs (1993), The Punisher (1993), Alien vs. Predator (1994) and X-Men: Children of the Atom (1994), as well as the games in Capcom’s pro-wrestling series, Saturday Night Slam Masters. For each of these, he’s credited as something like “Special Thanks” or “Capcom USA Support.” In his mind, this resulted both from Capcom’s discomfort working with external creatives and the fact that he, as a guy living in California, simply did not have a place in established corporate workflow.

“It was uncomfortable for them to have American designers,” he said. “The idea was that our job was supposed to write the story and translate things and then just sell the games. … They really didn’t know how to credit us because we wanted to be known as designers, and there was just a lot of resistance to that.”

Jimenez recalls how he was once tasked with writing the story for a Capcom arcade game starring Marvel’s The Punisher. He excitedly said yes, but then he was handed a video cassette that contained the completed game. Rather than conceive something from scratch, he was being asked to write a story around the existing Punisher game after the fact. This was not always the case, however. He points to the Dungeons & Dragons: Tower of Doom and its 1996 sequel, Shadow Over Mystara among the exceptions.

“I can honestly say that [Tower of Doom] is the game I did a lot on — the storyline and everything else and everything on it. … They credited me as ‘dungeon master.’ They wouldn’t list me as a designer, so I had to settle for that, which kind of ticked me off a bit,” he says. “I get a lot of people who say, ‘The Americans didn’t really do any of that. That was done over there.’”

To refute this, he holds up a phonebook-sized collection of papers.

“This is the design document for Dungeons & Dragons. I still have it. I still have the initial concept art and design work — everything else that went into that game. That was all on our end. So if anybody doubts it, I’ve got the proof right here.”

And, as he sees it, it’s a similar collection of design docs receipts that should prove that his involvement with Darkstalkers is on the level that he claims.

How Do You Create a Vampire?

It’s at this point that we got into a topic that I had made plans to bring up politely towards the end of the interview: the notion that Jimenez is mischaracterizing the role he played in creation of Darkstalkers and its characters.

In an interview appearing in the back pages of the 2014 book Darkstalkers: Official Complete Works, the game’s art director, Akira “Akiman” Yasuda, states that the concept was “brought up by” Katsuya Akitomo, who worked as an artist for Capcom at the time, and then was developed further by Junichi Ohno, who served as the game’s planner.

That origin story lines up more or less with a 1994 interview with Gamest in which Ohno and producer Noritaka Funamizu seem to say that the earliest version of the game had a roster populated with yokai before moving instead in favor of monsters that would be recognizable to non-Japanese players. Jimenez recalls the conception differently, saying that the idea began with him, and its earliest form was a fighting game featuring the monsters of the Universal Studios horror canon.

If you read the previous paragraph and reflexively decided that Jimenez’s story, being the one that seems the most unlike the others, must be false, I should explain to you that this kind of thing is actually common when it comes to video game history. I’ve trafficked in these stories for a while now, and if you have not, you might be surprised how often research leads to conflicting and sometimes contradictory accounts. Sometimes it’s tiny, specific things, sometimes it’s big things that shaped the industry, and sometimes it’s something that you thought everyone had already agreed on, only you find someone saying something radically different from what you thought was true. In fact, I’m working on a longer project about how some of the foundational stories for the creation of the Super Mario games frequently contradict each other in ways that are a lot more blatant that what we’re seeing in these differing narratives about how Darkstalkers came to exist. For what it’s worth, it’s not hard to imagine a situation where all of these stories about the creation of Darkstalkers could be true, and Jimenez points out that you can still find traces of his version of the story that link Darkstalkers back to Universal Studios horror movies. But he says he feels the need to clarify the matter regardless.

“There’s a British podcaster over on YouTube, and he’s come out and said I didn’t do any of this. And I really want to set the record straight, because I have the proof.”

Again he holds up a bound collection of papers that’s not quite as phonebook-level thick as the Dungeons & Dragons one, but it’s nonetheless chock full of documents and images showing the history of Darkstalkers.

“I can prove those characters are mine. Look at the names. Look at the names of those characters,” he says.

Here is how Jimenez recalls the creation of Darkstalkers and the role he played in it.

“Capcom was fishing around for what else we could do with this side-by-side fighting style system. Ideas were kicked around. I sent off a dozen lists. I wanted them to do the Universal movie monsters. I also wanted them to do the Toho monsters. I wanted them to do gods and goddesses. There were so many things. Marvel versus DC. I wanted to do all these things, but they liked the idea of monsters because they were fans of the anime Vampire Hunter D, so they already had the inkling of doing a vampire game. … I came along and said how about monsters? And the two sides kind of clicked on that. ‘Okay, let’s do movie monsters.’”

Jimenez explained that the Capcom higher-ups responded to his initial pitch of Universal monsters by suggesting that they just make up their own versions of these iconic characters rather than license the real ones. Although Jimenez said he would have preferred to use the Universal versions, he nonetheless got to work on a list of candidates.

“I had vampires, I had Frankenstein, I had the Creature from the Black Lagoon, the Gill Man, you know, a werewolf, all kinds of stuff. And then they came back afterwards and said, ‘Sure, these sound terrific. Make up some characters.’ I was on my way out the door. It was already 5:30, because of the time difference. I was ready to go home, and I was dead tired. So I sat down and said, fine, I’ll bang these out tonight. I made those characters up in about just under an hour.”

Now, if you’ve ever read this site before, you might know that I’m unusually interested in the origin of characters, of character names especially, and whenever these characters can be traced to some pop culture antecedent. As a result, I was very happy to hear Jimenez recount all of this for the cast of Darkstalkers.

Demitri

In mapping Darkstalkers onto Universal horror movies, it’s easy to peg Demitri as the series’ stand-in for Dracula. As Jimenez recalls, he wanted the connection to be even more explicit, as his initial idea for the central vampire’s name was Belasco — a tip of the hat to the real last name of Bela Lugosi, who played Dracula in 1931. The Hungarian-American actor who was born Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó. However, that name came into conflict with the Marvel villain Belasco, and it wasn’t a coincidence that the first Marvel-Capcom team up, 1994’s X-Men: Children of the Atom, was also in development. (It would hit arcades in December 1994, about five months after Darkstalkers debuted.)

“They were like, ‘We’re dealing with Marvel right now. We got to go easy on that,’” he says. “So I was like, ‘Wow, but that’s his real last name.’ I wanted to honor the guy. So I was kind of under the gun on that one.”

He says he ended up going with a “good, Slavic name” in Demitri, with his last name, Maximoff, simply coming from him brainstorming: “He’s just so cool. He’s the ultimate. He’s the max. The Maximum! And then I threw a little Russian twist on that: Demitri Maximoff.”

Morrigan

While Morrigan does not directly correspond to a figure from the Universal canon, it’s worth pointing out that initial conceptions of her had her being a female vampire — and indeed, just looking at her bat motif, it’s extremely easy to see that connection. But female vampires do have a place in the Universal canon. The first sequel to 1931’s Dracula is not 1943’s Son of Dracula, which introduces Alucard, but 1936’s Dracula’s Daughter, which features Gloria Holden as a female vamp.

Jimenez recalls that he suggested they make her a succubus instead, although the Capcom staffers weren’t initially familiar.

“They were like, ‘What’s a succubus?’ And I was like, ‘It’s a type of demon.’ And they’re like, ‘Oh, we already have a demon. We have Pyron. He’s kind of like a demon. What’s special about this one?’ So I was like, ‘Well, succubuses are kind of special, because they kill guys by screwing them to death.’”

That, he claims, went over very well, and thus, a video game icon was born. He also explains that he came up with her name by drawing from his reserve of weird and fantastical world folklore. In Irish folklore, the Morrigan is a female entity sometimes thought of as a goddess of war or fate. (NOTE: Jimenez also gave a source for Morrigan’s last name, Aensland, trying it to a female ruler, but I’m still awaiting a follow-up email on that one. Jimenez, you owe me an etymology!)

While Demitri was supposed to be the game’s main character — the Japanese name for the series is, after all, Vampire (ヴァンパイア or Vanpaia) and since Morrigan is a succubus, he is the game’s only actual bloodsucker — Morrigan has truly stolen the show and emerged as the most recognizable of the game’s cast.

“It just took off from there. Morrigan is the most popular one. I see her everywhere, man,” he says. “She appeals obviously to guys, because she’s a very sexual sex appeal character, you know, that’s kind of dangerous. And I think the ladies like her for the same reason they like Lara Croft. She’s strong. She’s tough. She’s not this willy-nilly princess.”

I agreed but also pointed out that another significant virtue to Morrigan is that unlike some dour-faced heroines, she also seems like she’s having a good time.

Jon Talbain

According to Jimenez, the best martial artist-werewolf in video game history takes his name from Sir John Talbot, Claude Rains’ character in the 1941 Universal film The Wolf Man. Technically, Rains’ character isn’t the werewolf but the father of the werewolf played by Lon Chaney Jr., but in my book it works regardless because Rains’ character kills Chaney’s, and Talbain is a character in conflict with himself, who pursued martial arts as a means of taming his inner beast.

In Japan, the character’s name is Gallon (ガロン or Garon), but Darkstalkers is an unusual case when it comes to video game localization because the English-language names are actually the originals, with the names unique to the Japanese version being the ones that were localized after the fact. In Japanese garō (餓狼 or がろう) means “hungry wolf” and in fact is part of the Japanese title for the Fatal Fury series: 餓狼伝説 or Garō Densetsu, “Legend of the Hungry Wolf.”

Rikuo

Jimenez acknowledges that the merman’s name is a tip of the hat to Ricou Browning, the swimmer and stuntman who played the titular monster in 1954’s Creature from the Black Lagoon. He also admits there’s a bit of parallelism here, in that there’s a running gag in the series about how Rikuo is strikingly attractive despite being a fish-man, and also Browning was actually a handsome guy despite playing a scary sea monster whose face was hidden by a mask the whole film.

In fact, Jimenez says he actually got to tell Ricou Browning that he’d paid homage to him in Darkstalkers. “I met him at Comic-Con back before he passed away. He was there at a table all alone. I freaked out. I was like Ricou Browning! Holy shit!” he says. “I mentioned what I had done kind of offhandedly. I didn’t want to, like, make him feel bad or anything. And he exploded. He thought that was the most fantastic thing ever.”

The Japanese version of the game also swaps out Rikuo’s name in favor of a new one: Aulbath. For the life of me I can’t figure out why or what this new name might mean. The katakana for it, オルバス, is sometimes also translated as something like Orbus.

Victor

Obviously, the Darkstalkers analogue for Frankenstein’s monster takes his name from the doctor who created said monster, but Jimenez acknowledges there was some modest wordplay happening in Victor’s last name, von Gerdenheim. “I said, ‘Okay, so Victor’s a good first name. Now we need something German. I wanted to keep it German. And I just looked at him and said, ‘What would imply strength?’ I thought about it. He’s like an I-beam, like a girder, and so I got to Gerdenheim. That’s a good, strong, German name that implies strength. Victor von Gerdenheim sounds like something Arnold might be able to play.”

They can’t all be deep cuts, people.

Anakaris

While the name of the undead Egyptian high priest in 1932’s The Mummy is Imhotep, the inspiration for Anakaris’ name instead comes from a later Universal Studios horror pic: 1942’s The Mummy’s Tomb, in which Lon Chaney Jr. plays a different embalmed monster, Kharis. He’d recur in The Mummy’s Ghost and The Mummy’s Curse (both 1944, somehow). Jimenez says he combined Kharis’ name with the word ankh, the ancient Egyptian symbol representing life to imply some kind of Egyptian version of everlasting life.

“To be corny about it, it was my feeble attempt to make eternal life, basically. Ankh-Kharis, the eternal mummy.”

Felicia

Technically, there are no catwomen in the Universal Studios canon — and really, there are few female monsters in general. Even the Hammer Horror has one film with a solo female big bad, 1964’s The Gorgon. However, catwomen do appear in horror movies that were screening around the time of Universal’s horror heyday: 1932’s Island of Lost Souls and 1942’s Cat People among them. So a female humanoid feline made enough sense to prevent Darkstalkers from being a complete sausage party.

Jimenez recalls that his initial conception for how Felicia would look was very different from how she turned out, however.

“I wanted to make her a werepanther. I wanted her to be this tall, graceful Maasai woman,” he says. “I had envisioned her as an African woman with short-cropped hair. And her special move was when she lunged at you, she would shapeshift into a black panther and claw you up and then spring back and shapeshift back.”

Obviously, that’s not how Felicia turned out. She’s less sleek black panther and more cottonball kitty cat. And although she’s wearing less than most female fighting characters, she’s also clearly meant to be the “cute” one in contrast to Morrigan being the “sexy” one. Jimenez says this was a battle he was destined to lose, and he puts the blame on Japanese avoidance of black characters. “And that’s that’s the polite way of putting it,” he says, recalling that an American boss pulled him aside and pointed out that fighting for his original version of Felicia would be an uphill battle.

What’s interesting about Felicia’s finalized design, I pointed out in my conversation with Jimenez, is that she’s sometimes (though not always) given a skin color that’s a little more tan than what the either humanoid characters get. Granted, that may be because characters like Demitri and Morrigan are dead and not getting much sunlight, but even still an interesting aspect to Felicia is that she fits in line with how Capcom would portray black women in games. The first playable black woman in a Capcom game would be Storm in X-Men: Children of the Atom, and her appearance in that game accurately reflects how she looks in the comics, with dark skin but stark white hair. Curiously, the next major black female character in a Capcom game would be Elena in 1997’s Street Fighter III. She is actually somewhat close to Jimenez’s original idea for Felicia, being tall, slender and graceful — but she has white hair like Storm. It would actually take until 2023 for Capcom to feature a prominent black female in one of their fighting games who didn’t have white hair — and it’s Street Fighter 6’s Kimberly Jackson, who’s rocking black braids — but I think it’s also worth considering that Felicia still ended up retaining some of elements of how Capcom used to visually code black female characters.

As for Felicia’s name, it’s not an allusion to the Marvel character Black Cat, Felicia Hardy, but instead a name that is just close enough to feline, Jimenez says, though it also happened that a coworker’s wife also had that name, and she eventually did find out that the Darkstalkers character had this in common with her. “Phil’s wife, Felicia, was one of the sweetest ladies I’ve met. Very shy, quiet lady. and And to see this big, rather bosomy cat lady sharing her name, she took it as a semi-compliment,” he said, laughing.

Lord Raptor

For the game’s punk rock zombie, Jimenez says he initially tried to pay homage to a decidedly non-Universal horror icon but had to go with a plan B instead.

“Raptor was a heartbreak for me because I wanted him originally to be called Romero,” he says, noting that he’s not sure why he wasn’t allowed to pay tribute to the Night of the Living Dead director George Romero, only that he based the substitute name on his appearance. Because Lord Raptor sports a Union Jack, Jimenez gave him a British title, and because the character’s boney, clawed feed looked like a hawk’s, he picked Raptor. And even that got some pushback from an American marketing person who thought people would connect the name too strongly with a certain 1993 dinosaur movie.

“[They] thought I was basing it on the dinosaurs from Jurassic Park, and here’s the quote of quotes: ‘Nobody’s going to remember Jurassic Park in a couple of years,’” he says with a laugh.

The Japanese version of the game renames Raptor, and again I can’t make heads or tails of what it might mean: Zabel Zarock (ザベル・ザロック or Zaberu Zarokku). If you have any theories, please tell me.

Bishamon

Jimenez recalls that he had only taken Bishamon as far as being a ghost, and it was actually the Japanese staff that put him in the cursed samurai armor. The character takes his name from the Japanese version of the Buddhist warrior god Vaiśravaṇa, Bishamonten (毘沙門天).

Sasquatch

The comic relief yeti is maybe the most straightforward of the characters, although Jimenez notes that he thought the series might one day include a brown, regular Bigfoot as a counterpart to the snow-dwelling version.

Huitzil

As Jimenez recalls, the idea was always to make the robot boss distinctly mesoamerican in design, and so he named him after the Aztec god Huītzilōpōchtli. In this case, he thinks the Japanese name for the character, Phobos, might be better, but I actually said I like the original name more, because I thought it was better to have this ancient robot reflect in his name the culture that his design was trying to evoke.

Jimenez did point out that his original idea for Huitzil’s ending in the 1995 sequel, Night Warriors: Darkstalkers’ Revenge, went a little bit further than what’s shown in the game.

“I’m part Native American, and the original ending that I wrote, my boss was like ‘There’s no way we’re going to let this out of here,’” he said. “But I wrote an ending where you find out that the Aztecs had a vision of this alien coming down and that the alien would destroy all their people. So they built this huge army of Huitzils. It’s almost like the Terracotta Army. They’re sealed up in this mountain. And when you win the game as Hutzil, he activates his program to eliminate all alien, non-native life from the North American continent. And the last image you’d see is him grabbing all these people and throwing them on boats while the Indians cheer in the background.”

As it stands, the ending has Huitzil returning to Tenochtitlan, finding “both the northern and southern continent infested with non-aboriginals” and then activating a removal program, but you don’t actually see it happen.

Pyron

Again, it’s about a straightforward as you’d think: “I looked at Pyron. He was all energy and fire. So I thought Pyro, Pyron, and that would be his thing.”

Donovan

But friends, Donovan is not quite as straightforward, and I have to admit, there has been something about his full name, Donovan Baine, that reminded me of something that I just couldn’t put my finger on all these years, and Jimenez had to say it before I finally made the connection.

Because Jimenez is a Marvel guy, my guess was always that Donovan, the half-vampire monster hunter wielding a sword, might be inspired by Blade. He’s not, says Jimenez, and he’s actually based on Solomon Kane, a character created by Robert E. Howard, who’d later go on to create Conan the Barbarian. Much like Donovan, Solomon Kane is a grim-faced religious zealot who travels the world in an effort to hunt and vanquish evil. I was kind of embarrassed that I didn’t make the connection sooner. Donovan’s last name is even Baine, so his full name rhymes with Solomon Kane’s.

But that’s not all that went into Donovan’s DNA; he’s also Carl Kolchak, the character played by Darren McGavin in two made-for-TV horror movies that eventually spawned a one-season wonder on ABC, Kolchak: The Night Stalker, about a newspaper reporter who investigated paranormal cases. Airing in 1974 and 1975, it was essentially a predecessor for The X-Files, and X-Files creator Chris Carter had acknowledged that it was a major inspiration for him.

“Kolchak was one of my heroes when I was a kid,” Jimenez says. “I love brainy characters. I love characters that outthink their opponents. And so we put the the idea of a hunter in there, and then they came back with Donovan. He was almost like a priest, with the beads and all that, and I saw what they were going for with that.”

Jimenez says he saw Anita, the Wednesday Addams-esque little girl who accompanies Donovan into fights but does not participate, as not just a sidekick but a necessary grounding force, because the more monsters Donovan slays, the more he absorbs the darkness.

“She kind of balances [the darkness] off. You know, she kind of keeps him from going completely dark,” he says. “I really didn’t have the idea of him and being half-vampire. I wanted him to be this human that just got darker the more he absorbed, along the lines of that Nietzsche quote, ‘Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you look into the abyss, it looks back into you.’ In his ending, he does eventually go over completely, you know. … Which was sad, but [Capcom Japan] thought that was too sad, but I was like, ‘No, that’s gothic horror. That’s exactly the way gothic horror works. It’s called gothic horror, not gothic comedy.”

Jimenez noted that at one point he was considering calling him Duncan, but Donovan “had a more old-fashioned ring to it.” Etymologically, both names imply literal darkness, which works with the themes of metaphorical darkness Jimenez saw for this character.

Hsien-Ko

And finally, we have another breakout character, Hsien-Ko, the jiangshi who debuted in the sequel alongside Donovan but who has proven one of the most iconic of all the Darkstalkers characters. Jiangshi do not appear in the Universal horror canon, but they are staples of Hong Kong cinema, especially in the 1990s. Jimenez admits to not knowing all that much about these Chinese hopping vampires before beginning his research, and not informing the creation of this character as much as others, although he does say that her name came from a Chinese girl he went to school with named Hsien.

“I kind of cheated a little bit and went with that,” he said. “I can honestly say I really didn’t do too much on her background because I was unfamiliar with the character. And I felt bad, but then my wife was kind of like ‘Yeah, but how many of them are going to know who Solomon Kane is?’ And then, you know, it balances out.”

Stalking the Truth

Perhaps it’s appropriate that the third Darkstalkers game, 1997’s Vampire Savior: The Lord of Vampire, takes place in an alternate dimension from the first two games because as Jimenez sees it, it’s doing something else entirely. He had no creative input on the final title, which ditched Donovan, Huitzil and Pyron and introduced four new characters: Jedah, a Grim Reaper-looking demon who wears a Japanese high school uniform; Q-Bee, a demonic bee girl; Lilith, a sort of “little sister” to Morrigan; and finally B.B. Hood, an assault rifle-toting Little Red Riding Hood type about whom I will be writing a separate post in the near future. In short, it’s a departure from the kind sources the first game drew on.

“I had already left Capcom by then. I’m kind of glad I did because some of the characters they came up with, I’m like… eh,” he says. “Whereas the original Darkstalkers, it is pop culture, but it’s classic pop culture.”

Of course, Jimenez can readily name various Universal monsters he wishes he could have included in the original Darkstalkers roster.

“If you want to know what characters didn’t make it, just look at any of those monster movies from the 30s and 40s,” he says. “I wanted to do a Phantom of the Opera character. I wanted Jekyll and Hyde. I wanted to do the Invisible Man, who I would have had in the bandages, and then his special coat would be to drop his coat so he’d be a pair of gloves floating in the air, punching at you.”

Jimenez’s description of how an Invisible Man character could work would seem to match statements Junichi Ohno made in that 1994 Gamest magazine interview, although for the record Jimenez’s version is more detailed. Perhaps it’s a coincidence. And if you’re a skeptic, I suppose you could say that Jimenez is just elaborating on something shared by Capcom of Japan years ago. But more often than not, his descriptions of the game he originally envisioned just make a lot of sense as far as what Darkstalkers turned out to be. Even after it moved away from an explicitly Universal monster-themed fighting game, a lot of those touches still remain. And there’s a uniformity to the kind of horror nerd stuff he’s into that just keeps popping up again and again, to the point that I couldn’t dismiss the idea that he truly had a hand in drafting the game’s blueprints.

Take the title, for example. I nearly forgot to ask him how that, of all things, ended up being what the game was called in the west, but when he explained it, it just made a lot of sense, especially given what we’d already discussed regarding the inspiration for a certain character.

“I named Darkstalkers Darkstalkers. I’m the one that came up with the Darkstalkers name. I just like the name Darkstalkers, you know, in part because of one of my favorite shows when I was a kid. You know what I’m talking about, obviously, right?”

Of course, I did. He was talking about Kolchak: The Night Stalker again — and for a second time, I was embarrassed that this connection was staring me in the face all these years but I never put it together. The monster fighting game is named after the granddaddy of the “monster of the week” procedural shows.

“I think everybody should watch Kolchak: The Night Stalker. It’s awesome. And I loved it, but I didn’t want to call [the game] Night Stalkers, so I spun it around a little bit and said, ‘How about Darkstalkers?’ Because this is all monsters fighting monsters. There are no heroes, really. They’re all dark.”

This is actually a big deal, but in order to convey to you what a big deal it is, I’m going to have to step away from video games for a paragraph or three to talk about TV history. (And yes, by the way, I *do* have a TV history podcast where I do this kind of thing a lot.) I cannot express to you what a “you had to be there” kind of thing Kolchak: The Night Stalker was and still is. Following two moderately successful TV movies, the show aired during the 1974-75 TV season, where it pulled absolutely dismal ratings, behind even Hot L Baltimore, an absolute bomb of a sitcom that despite being developed by Norman Lear is not available anywhere online today, even though Lear’s poorest TV efforts still get held in relatively high esteem. To Kolchak’s credit, it at least did better than The Sonny Comedy Revue, which is what became of the Sonny & Cher Comedy Hour after the couple divorced because Cher realized she didn’t need Sonny, but essentially no one was watching any of these, even back in the era when cable and streaming didn’t exist and there were only three commercial broadcast TV networks.

Sure, Kolchak: The Night Stalker did have somewhat of an afterlife beyond its cancellation — mostly late-night syndication, though it eventually aired in full on the Sci-Fi Channel in the 1990s. For years, however, the biggest moment this TV show had in the spotlight was in 1998, — after the final Darkstalkers game, notably — when Darren McGavin guested on The X-Files as Arthur Dales, an retired FBI agent who actually began the paranormal investigations that give that show its name. Most people only know of Kolchak as a result of its meta connection to The X-Files.

Although Kolchak did actually air in Japan — in 1976 on Nippon Television, where it was retitled 事件記者コルチャック or Crime Reporter Kolchak — it just makes too much sense that a guy Alex Jimenez’s age would have latched onto this show back in the day and then eventually found not one but two separate ways to pay homage to it in a horror-themed fighting game: in the title and again in the backstory for Donovan, whom I discussed earlier. To me, the fact that this relatively obscure TV show would surface twice, in two more or less unrelated ways, is very telling. I’ve interviewed a lot of creatives about their work over the years, and when someone is discussing the influences that shape what they do, they can often explain how one thing can affect their efforts in different ways that are often invisible until it’s explained. And that’s the exact vibe I get when Jimenez discusses how Kolchak: The Night Stalker imprinted on him to the point that he couldn’t keep it out of his work if he tried.

Back when I worked at a newspaper — just like Carl Kolchak! — I had a boss who had a certain way of describing how an investigative reporter would get to the truth: “It rhymes,” he would say. And that meant that the information was falling into place in a way that the connections were apparent even if every detail hadn’t been filled in yet. To close the case on this one, I’d have to interview Capcom staff and get them to give their recollection of Jimenez’s creative role in creating Darkstalkers. And maybe I’ll do that one day, when I have the time and the access and the budget for live translation, but for the moment, I feel good saying that this really does seem to rhyme.

For what it’s worth, I concluded my interview with Jimenez telling him that the Video Game History Foundation would love to scan and upload his files should he ever feel inclined to share. More than a few video game creators have done this, and it’s an invaluable resource for people like me who are trying to make sense of the contradictions and half-remembered stories that tell us where our favorite games come from.

And while I don’t know what the future holds for Darkstalkers, I’m happy to shed a little moonlight on its past.

Alex Jimenez, meanwhile, has one final clarification he wanted on the record.

“It’s important to say that I never claimed that I created the game Darkstalkers, because no one video game is made by one person,” he says. “Darkstalkers and Dungeons & Dragons both, the reason they worked was because we had a fantastic dev team in Japan. We had some incredible artists and animators over there, awesome programmers. We had just terrific people all around. And in America, we did too. We had some great folks in the States. And I’m not trying to say that I created the game, you know, but I was honored to work on the team that did.

Miscellaneous Notes

As far as I know, Capcom is not working on a new Darkstalkers game. So for the moment, it seems like the most likely way we’d get to see any of these characters again would be if, for example, Morrigan or someone popped up in Street Fighter 6. That might seem like a weird proposition, I admit, but the news that Ingrid, of all characters, will be showing up in that game seems weird as well, just because she’s a little more supernatural than we’re used to seeing in this particular series. What’s interesting about Darkstalkers in relation to Street Fighter is that I can’t actually think of a canonical example of these two series existing in the same universe the way Final Fight, Captain Commando and other franchises do. There’s even that weird link between Street Fighter and Red Earth despite the latter being firmly in the fantasy genre in the way that Street Fighter really isn’t. So am I missing something? Or has Darkstalkers remained separate from Street Fighter so far?

And then here’s a funny story about the Darkstalkers animated series and the rather spectacular way that he originally tried to end it.

I got called in [by our head of licensing] in May of 1995 and was asked “Alex-san, did you ever work on a game called Darkstalkers?” And I’m like “Yeah, I worked on it a lot.” He goes, “What did you do?” And I say, “I designed it. I created some of the characters and whatnot.” And he said “Oh, terrific. We licensed it to make a cartoon show.” I was ecstatic because at the time in the 90s we had some fantastic cartoons. I was thinking Gargoyles-level, you know? And so I was like “It’s already May, right? If we can get this stuff wrapped up and written, they might have the animation done. I figured, okay, it’s going to be a mid-season replacement coming out January, February of next year. But then he’s like “Oh, it’s coming out in September.” And I think he means September of next year, but he says, “No, September this year. I was like, “How is that possible?” And he tells me that they wanted me to review the first six episodes because they’re done already. So I do… and I didn’t have much to say on that one, you know? I mean, I got the character of Harry and, you know, they wanted to have a kid character. So they threw in Harry and, I came up with the background of him being Merlin’s descendant. After the eighth episode, I got to give a little more input. I was able to actually get the stories before they were animated. And I got to work with a fantastic writer named Richard Mueller, who worked on The Tick. Toward the end of the series, I knew we weren’t going to get renewed. I mean, I was looking at the ratings. I’m like, we’re being beaten by the farm report. They were showing the cartoon at 6:30 a.m. on Sundays, you know, so I’m like, you know, we’re not coming back. you So Richard calls me up in my office and goes, well, we got one more left to do. What do you want to do? And I was like, “We’re not coming back, Richard. We’re not going to get renewed.” He goes, “Yeah, I know, but we still got one more to do. What do you want to do?” And I got kind of evil and went, “Let’s go Shakespearean. Let’s kill them all off. He started laughing. He’s like, can you do that? And I go, I created them. I can destroy them. They are my children to destroy. and he started laughing. He’s like, okay, Madam Medea, you want to do this? So we did it. We wrote the episode where they have this huge battle and they all get wiped out. And the last one is Harry and he’s facing up against Dimitri, who is super charged and super powerful because he’s drained everybody else. Harry, he summons all of his power and he does one last bolt and strikes him down and wipes out Dimitri. Then the strain hits him and Harry just gets on his knees and keels over, fade out, the end. So... I sent this off to Japan because they had to review all the scripts. And at 2:30 in the morning, American time, my phone rings. I pick up my phone and hear this voice: “Are you out of fucking mind? You can you can’t kill off the characters. We’re still selling the game.” I told them nobody’s watching this anyway. What the hell? But they were like, “No, you can’t do that. I told them they’re my children. I created them. And they were like, “Yeah, but you created them for us.”