During my visit to Samsung’s home appliance R&D facility in Seoul, Jay Yoon, Corporate VP and Head of the Refrigerator R&D Group, explained something remarkable about the development of their AI Hybrid Cooling refrigerator. His team had completely redesigned the refrigerator’s internal layout mid-development, not to fix a problem, but to maximize consumer benefits. The Peltier cooling chip system worked perfectly in its original rear-mounted position. The engineering was sound. But through continued collaboration between Samsung Research and the product development team, they discovered that repositioning the entire coo…

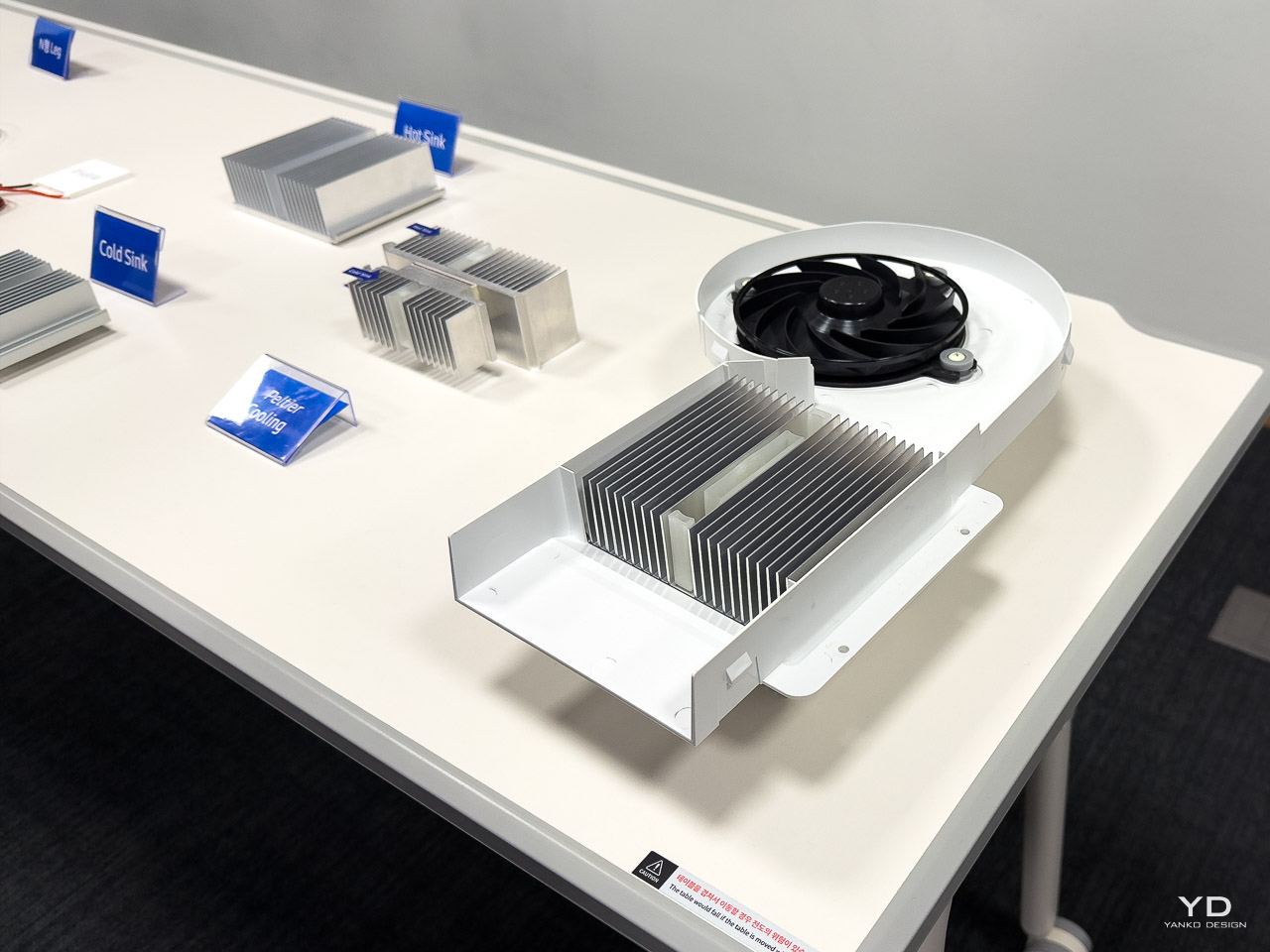

During my visit to Samsung’s home appliance R&D facility in Seoul, Jay Yoon, Corporate VP and Head of the Refrigerator R&D Group, explained something remarkable about the development of their AI Hybrid Cooling refrigerator. His team had completely redesigned the refrigerator’s internal layout mid-development, not to fix a problem, but to maximize consumer benefits. The Peltier cooling chip system worked perfectly in its original rear-mounted position. The engineering was sound. But through continued collaboration between Samsung Research and the product development team, they discovered that repositioning the entire cooling system to the top would dramatically improve interior space and thermal performance. “We completely discarded the layout we initially designed,” Yoon explained, describing how the team abandoned months of engineering work to pursue the better solution.

Designer: Samsung

The team wasn’t fixing a problem. They were refusing to settle for “good enough.”

That willingness to abandon comfortable solutions appeared throughout the two-day facility tour. Over presentations, lab tours, and design team sessions, I watched Samsung wrestle with fundamental challenges about how appliances should integrate into modern homes and how global products can feel locally relevant.

From Statement Pieces to Spatial Harmony

Samsung’s design evolution over the past decade reflects a broader shift in how we think about appliances in our homes. The design team traced this progression explicitly during their presentation. “In the past, Samsung refrigerators featured bold contours and glamorous presence that stood out in kitchen spaces,” explained the design team during their presentation. These were appliances that demanded attention, with dramatic lines and high-contrast finishes that made them focal points in any kitchen. The design language spoke loudly: this is premium technology, and you should notice it.

Today, that approach has inverted.

“Today, our designs focus on a flat and geometric look that blends seamlessly with modern interiors,” the design team explained. The Bespoke line exemplifies this shift, offering customizable panels that let consumers match their appliances to their specific aesthetic rather than forcing rooms to adapt to the appliance. As the presentation emphasized, “The Bespoke was the first product tailored to the consumer, rather than led by the manufacturer.”

The evolution makes sense when you consider how kitchens function now. Open floor plans mean appliances sit in continuous sightlines with living spaces. Minimalist interior design emphasizes clean surfaces and reduced visual noise. An appliance that demands attention disrupts the careful balance homeowners work to create. Samsung’s current design language acknowledges this reality, focusing on integration rather than statements.

This shift required the design team to develop new methods for creating visual interest without resorting to dramatic forms. They’ve focused on proportion, material quality, and subtle details. During the product showcase, a designer pointed out their signature element: “This very narrow window is Samsung’s signature design identity.”

The Three-Stage Design Process

Samsung’s design team walked through their development methodology, which operates in three distinct phases. Understanding this structure reveals how they balance innovation with manufacturability, and why certain design decisions take precedence over others.

Advanced Design comes first. “The first stage, called advanced design, is the very early phase where we explore innovative design directions and develop concepts,” explained the design team. “In this stage, rather than focusing on manufacturability, we aim to discover new opportunities through future-oriented challenges.” The team researches global megatrends, tracks generational differences in appliance expectations, and studies post-pandemic changes in home behavior. This phase feeds the innovation pipeline with ideas that might become products in three to five years.

Archetype Design follows. “The second stage is Archetype Design, where we define the core design elements and identities and create prototypes that closely resemble our actual designs,” the team explained. Engineering constraints enter the conversation. Manufacturing realities impose boundaries. Cost structures become factors. The Peltier chip repositioning happened during this phase, when the team realized their initial layout compromised the consumer benefits they were trying to deliver.

Final Design brings everything to market-ready form. “The final phase, where we refine the archetype design into a market-ready form, taking into account feasibility and optimization,” as the presentation described it. The design gets refined for production efficiency, tested for durability, validated through consumer preference studies, and engineered for serviceability. The team emphasized that this isn’t where creativity dies. It’s where creative solutions prove whether they can survive contact with reality.

Some ideas make it through with minimal changes. Others, like the refrigerator layout, require fundamental reimagining even at this late stage.

What struck me about this process is how much research grounds every stage. The team doesn’t rely on designer intuition alone. They conduct extensive consumer preference studies to evaluate design competitiveness. They analyze furniture design trends to ensure their appliances harmonize with what consumers are actually buying for their homes. They run localized projects like their U.S. Laundry Space and Market Trend Sensing study to understand regional differences in how people interact with appliances. Design decisions emerge from this research foundation rather than aesthetic preference alone.

Unibody Express: Washing Machine Minimalism

The washing machine design team introduced their Unibody Express philosophy as a case study in essentialist thinking. The name itself signals the approach: eliminate everything unnecessary until only the fundamental interaction remains.

Their starting point was provocative. Rather than beginning with a washing machine shape and refining it, they asked what the essential form should be. As Sarah Choi, Head of the Living Design Group, explained during the presentation: “We’ve gone back to basics to redefine design and to make people’s lives better. With the design philosophy of Samsung that is essential, innovative, harmonious.” She described stripping away everything extraneous to reach the core: “But rather something fundamental and pure. A single rectangle. This is the essential space where we meet our users.” The presentation showed how they removed decorative elements systematically. “We removed many decorative elements that make up the washing machine. Focused on the fundamental material, the steel.”

What remained was steel, glass, and the pure geometry of the rectangle.

This sounds simple. Executing it proved complex. Removing decorative elements means the fundamental materials and proportions carry all the aesthetic weight. There’s nowhere to hide manufacturing imperfections or component compromises. The team explained they needed higher standards than previous designs required. The steel finish, glass clarity, and panel alignments all had to be essentially perfect since there was nothing else to draw the eye. As the team explained, “This design form allows for effective management of product design variations while enabling efficient operations through part standardization.”

The result aligns with broader movements in industrial design toward essential forms and honest materials. But unlike some minimalist exercises that prioritize aesthetic purity over function, the Unibody Express philosophy emerged from user research. The team studied how people actually interact with washing machines, identified the core interaction space, and designed around that fundamental relationship.

The minimalism isn’t stylistic. It’s structural, based on understanding what matters to someone doing laundry.

CMF: The Language of Premium Materials

Color, Material, and Finish design operates as its own discipline within Samsung’s structure, and watching their CMF team present revealed how much invisible work creates the perception of quality in appliances.

The team expressed particular pride in their black metal work. During the CMF showcase, a designer explained: “Real metal is used by all companies, but we are proud of black metal and have been leading trends in this finish.” Their newest premium direction uses ribbed aluminum. “This is a new material that has not been used much in product design. Aluminum that was used a lot in IT devices,” Oh noted, describing how they applied a ribbed design to create a premium aesthetic for refrigerators in the Korean market.

Glass appears across product categories, from cooking appliances to refrigerators to water purifiers, with the team developing methods to match colors and textures across these different applications. The upcoming ceramic collaboration represents their most ambitious material innovation. During the showcase of unreleased products, Oh explained: “This is ceramic from Italian company Mutina. Ceramic is widely used in furniture and table interiors, but we have applied ceramic CMF to refrigerators for the first time with the technology to apply it to product design.”

What makes CMF design fascinating is how it operates at the intersection of aesthetics and material science. “We continue to study interior design trends across diverse regions, from Asia to the Americas and Europe, through online learning,” explained Oh. “By updating and analyzing the latest trends, we ensure that our home appliances harmonize seamlessly with consumers’ real-life environments.” They create digital twin virtual spaces to simulate how their CMF choices will appear in these real-world contexts. “The CMF combines these elements into two tones, bright and dark, that complement each unique space and its character,” the presentation emphasized.

The team also experiments with perception engineering. “We have the skill to create textures and printing technology that can give a stone feel,” Oh explained during the showcase, demonstrating samples that used glass and coating techniques to simulate stone and ceramic aesthetics without the weight and cost constraints of actual stone or ceramic components.

During the CMF showcase, Oh explained her team’s philosophy of holistic interior integration: “We design not only product design, but also furniture, interior, and fabrics to complete the overall interior mood by harmonizing with these paints and materials.”

Sustainability as Design Constraint

The sustainability integration revealed during the CMF presentation felt refreshingly pragmatic rather than performative.

“All glass samples are made of recycled materials,” Oh explained during the CMF showcase. “Samsung has been working to replace glass products with recycled glass for several years now.” For their premium aluminum products, they’ve adopted a hybrid approach: “The front uses a thin new aluminum layer that can reflect new colors because it needs to express beauty,” while “the base metal behind uses recycled aluminum.” The team was frank about sustainability constraints. When asked about expanding recycled content further, they acknowledged: “It would be most efficient to make suggestions without increasing consumer prices… If there is a need that consumers can tolerate to that extent, we can do it.”

Regional Design: Ergonomics Meets Culture

The most compelling design challenge Samsung faces is creating global products that feel locally appropriate. Refrigerator design makes this visible.

The design team explained: “T-Type is a popular platform here in Asia, whereas the French door type is also preferred in North America.” They detailed the structural differences: “The T-type has segmented freezer box at the bottom, while the French door type uses large capacity freezer drawers, also located at the bottom.” The design presentation emphasized these aren’t arbitrary preferences. They reflect different food cultures, shopping patterns, and kitchen spatial organizations.

The design team explained that understanding these regional differences requires ethnographic research, not just market data. How do Korean families shop for and store kimchi? How do American households manage bulk purchases from warehouse stores? What food preservation expectations exist in European markets with smaller, more frequent shopping patterns? Design decisions about interior layout, drawer sizing, and temperature zone configurations all flow from understanding these cultural contexts.

This regional customization extends beyond refrigerators. Kitchen appliance dimensions differ between markets. During the product showcase, Claire Lee, Head of Kitchen Design Group, explained: “This is a 30-inch wall oven… a product specialized for the North American market,” then showed a contrasting model: “Unlike the North American 30-inch model, this is a 24-inch spec model specialized for the European and Korean markets.” Cooking technology preferences vary too. Lee noted that in North America, “traditionally gas products were common,” but emphasized that “induction products are rapidly expanding” as consumers shift away from gas cooking.

Samsung designs platforms that can accommodate these variations while maintaining design language consistency across regions.

What This Means for Appliance Design’s Future

Samsung’s approach suggests appliance design is entering a more sophisticated phase. The days of technology-first thinking, where impressive specs drove product development and design followed, are giving way to human-centered processes where design insight drives technology application. The Peltier chip repositioning exemplifies this: the technology was ready, but the design team’s understanding of user benefit justified completely reworking the internal architecture.

This shift requires different skills from designers. They need fluency in material science, manufacturing constraints, cultural differences, and sustainability considerations alongside traditional aesthetic capabilities. They need research methodologies to validate assumptions about user preferences. They need collaborative skills to work with engineers who might resist mid-development redesigns.

The Samsung design team’s structure, with specialists in product design, CMF design, design innovation, and design strategy all collaborating, reflects this expanded scope.

The risk in this approach is designing for an idealized user rather than real people. The safety lies in the research foundation. Samsung’s investment in consumer preference studies, localized market sensing projects, and continuous trend analysis keeps their design process grounded in actual behavior rather than designer intuition about what people should want.

Watching their team work through these challenges over two days in Seoul revealed an organization taking appliance design seriously as a discipline. Not as styling applied to engineered products, but as a fundamental methodology for understanding how technology should integrate into daily life.

Whether this produces better appliances remains to be seen. But it definitely produces more thoughtfully considered ones.