Published on January 25, 2026 6:09 PM GMT

This post is an informal preliminary writeup of a project that I’ve been working on with friends and collaborators. Some of the theory was developed jointly with Zohar Ringel, and we hope to write a more formal paper on it this year. Experiments are joint with Lucas Teixeira (and also an extensive use of llm assistants). This work is part of the research agenda we have been running with Lucas Teixeira and Lauren Greenspan at my organization Principles of Intelligence (formerly PIBBSS), and Lauren helped in writing this post.

Introduction

Pre-introduction

I have had trouble writing an introduction to this post. It combines three aspects of interpretability that I like and have thou…

Published on January 25, 2026 6:09 PM GMT

This post is an informal preliminary writeup of a project that I’ve been working on with friends and collaborators. Some of the theory was developed jointly with Zohar Ringel, and we hope to write a more formal paper on it this year. Experiments are joint with Lucas Teixeira (and also an extensive use of llm assistants). This work is part of the research agenda we have been running with Lucas Teixeira and Lauren Greenspan at my organization Principles of Intelligence (formerly PIBBSS), and Lauren helped in writing this post.

Introduction

Pre-introduction

I have had trouble writing an introduction to this post. It combines three aspects of interpretability that I like and have thought about in the last two years:

- Questions about computation in superposition

- The mean field approach to understanding neural nets. This is a way of describing neural nets as multi-particle statistical theories, and has been applied in contexts of both Bayesian and SGD learning that has had significant success in the last few years. For example the only currently known exact theoretical prediction for the neuron distribution and grokking phase transition in a modular addition instance is obtained via this theory.

- This connects to the agenda we are running at PIBBSS on multi-scale structure in neural nets, and to physical theories of renormalization that study when phenomena at one scale can be decoupled from another. The model here exhibits noisy interactions between first-order-independent components[1] mediated by a notion of frustration noise - a kind of “frozen noise” inherited from a distinct scale that we can understand theoretically in a renormalization-adjacent way.

My inclination is to include all of these in this draft. I am tempted to write a very general introduction which tries to introduce all three phenomena and explain how they are linked together via the experimental context I’ll present here. However, this would be confusing and hard to read – people tend to like my technical writing much better when I take to heart the advice: “you get about five words”.

So for this post I will focus on one aspect of the work, which is related to the physical notion of frustration and the effect this interesting physical structure has on the rest of the system via a source of irreducible noise. Thus if I were to summarize a five-work takeaway I want to explain in this post, it is this:

Loss landscapes have irreducible noise.

In some ways this is obvious: real data is noisy and has lots of randomness. But the present work shows that noise is even more fundamental than randomness from data. Even in settings where the data distribution is highly symmetric and structured and the neural net is trained on infinite data, interference in the network itself (caused by a complex system responding to conflicting incentives) leads to unavoidable fluctuations in the loss landscape. In some sense this is good news for interpretability: physical systems with irreducible noise will often tend towards having more independence between structures at different scales and can be more amenable to causal decoupling and renormalization-based analyses. Moreover, if we can understand the structure and source of the noise, we can incorporate it into interpretability analyses.

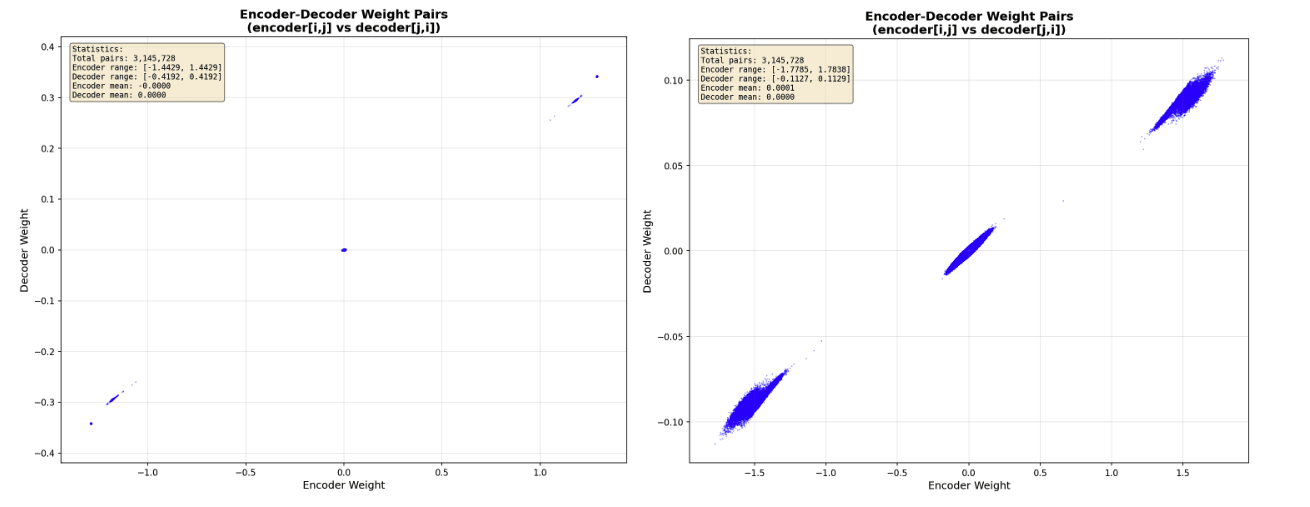

In this case the small-scale noise in the landscape is induced by an emergent property of the system at a larger scale. Namely, early in training the weights of this system develop a coarse large-scale structure similar to the discrete up/down spins of a magnet. For reasons related to interference in data with superposition, the discrete structure is frustrated and therefore in some sense forced to be asymmetric and random. The frustrated structures on a large scale interact with small fluctuations of the system on a small scale, and lead to microscopic random ripples that follow a similar physics to the impurities in a semiconducting metal.

The task

In this work we analyze a task that originally comes from our paper on Computation in Superposition (CiS).

Sparse data with superposition was originally studied in the field of compressed sensing and dictionary learning. Analyzing modern transformer networks using techniques from this field (especially sparse autoencoders) has led to a paradigm shift in interpretability over the last 3 years. Researchers have found that the hidden-layer activation data in transformers is mathematically well-described by sparse superpositional combinations of so-called “dictionary features” or SAE features; moreover these features have nice interpretability properties, and variants of SAE’s have provided some of the best unsupervised interpretability techniques used in the last few years[2].

In our CiS paper we theoretically probe the question of whether the efficient linear encoding of sparse data provided by superposition can extend to an efficient compression of a computation involving sparse data (and we find that indeed this is possible, at least in theory). A key part of our analysis hinges on managing a certain error source called interference. It is equivalent to asking whether a neural net can adequately reconstruct a noisy sparse input in (think of a 2-hot vector like , with added Gaussian noise while passing it through a narrow hidden layer with . The narrowness forces the neural net to use superposition in the hidden layer (here the input dimension is the feature dimension. In our CiS paper we use different terminology and the feature dimension is called ). In the presence of superposition, it is actually impossible to get perfect reconstruction, so training with this target is equivalent to asking “how close to the theoretically minimal reconstruction error will be learned by a real neural net”.

In the CiS paper we show that a reconstruction that is “close enough” to optimal for our purposes is possible. We do this by “manually” constructing a 2-layer neural net (with one layer of nonlinearity) that achieves a reasonable interference error.

This raises the interesting question of whether an actual 2-layer network trained on this task would learn to manage interference, and what algorithm it would learn if it did; we do not treat this in our CiS paper. It is this sparse denoising task that I am interested in for the present work. The task is similar in spirit to Christ Olah’s Toy Models of Superposition (TMS) setting.

Below, I explain the details of the task and the architecture. For convenience of readers who are less interested in details and want to get to the general loss-landscape and physical aspects of the work, the rest of the section is collapsible.

The details (reconstructing sparse inputs via superposition in a hidden layer)

Our model differs from Chris Olah’s TMS task in two essential ways. First, the nonlinearity is applied in the hidden layer (as is more conventional) rather than in the last layer as in that work. Second and crucially, while the TMS task’s hidden layer (where superposition occurs) is 2-dimensional, we are interested in contexts where the hidden layer is itself high-dimensional (though not as large as the input and output layers), as this is the context where the compressibility benefit from compressed sensing really shine. Less essentially, our data has noise (rather than being a straight autoencoder as in TMS), and the loss is modified to avoid a degeneracy of MSE loss in this setting.

The task: details

At the end of the day the task we want our neural net to try to learn is as follows.

Input: our input in is a sparse boolean vector plus noise, (here in experiments, is a 2-hot or 3-hot vector, so something like and is Gaussian noise which is standard deviation on a coordinatewise level). We think of as the feature basis.

Output: the “denoised” vector . As a function, this is equivalent to learning the coordinatewise “round to nearest integer” function.

Architecture: we use an architecture that forces superposition, with a single narrow hidden layer where . Otherwise the architecture is a conventional neural net architecture with a coordinatewise nonlinearity at the middle layer, so the layers are:

Fine print: There are subtleties that I don’t want to spend too much time on, about what loss and nonlinearity I’m using in the task, and what specific range of values I’m using for the hidden dimension h and the feature dimension d. In experiments I use a specific class of choices that make the theory easier and that let us see very nice theory-experimental agreement. In particular for loss, a usual MSE loss has bad denoising properties since it encourages returning zero in the regime of interest (this is because sparsity means that most of my “denoised coordinates” should be 0, and removing all noise from these by returning 0 is essentially optimal from a “straight MSE loss” perspective, though it’s useless from the perspective of sparse computation). The loss I actually use is re-balanced to discourage this. Also for theory reasons, things are cleaner if we don’t include biases and the nonlinearity function has some specific exotic properties (specifically, I use a function which is analytic, odd, has and is bounded. The specific function I use is ). The theory is also nicer in a specific (though extensive) range of values for the feature dimension