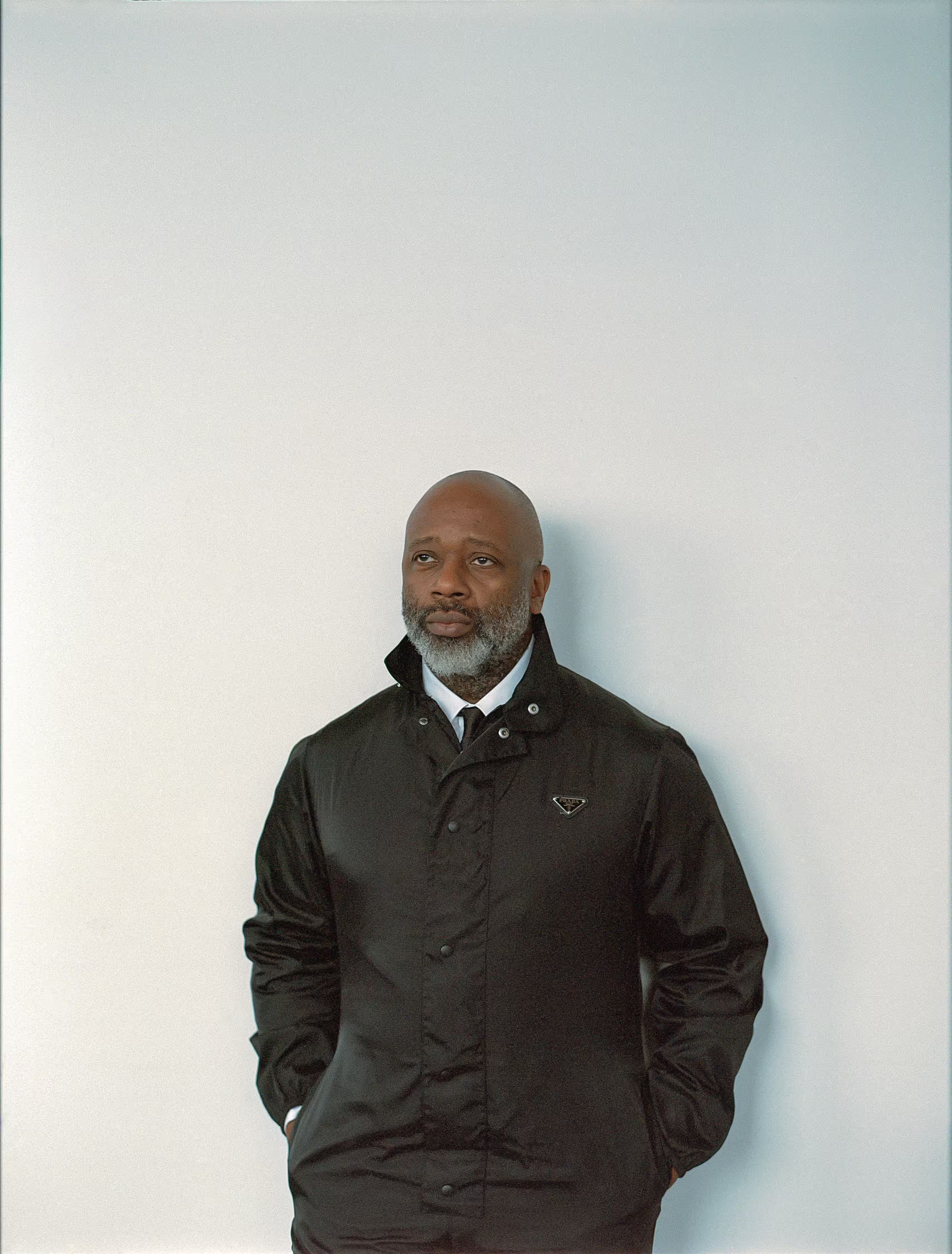

Theaster Gates wears jumpsuit, shirt, and tie by PRADA.

What elevates a nondescript space into a work of art—and what ties it back to reality? Such queries bring Theaster Gates and Carsten Höller to the limits of imagination. The artists’ respective practices travel down paths that might appear divergent on the surface yet run parallel in the bigger vision. For Gates, histories become source material, bits and pieces of memories to finesse into revelations. The 52-year-old was born and raised in Chicago and studied urban planning and ceramics; today his conceptual practice encapsulates everything from public-involved artworks and architectural renovations to paintings, sculptures, and installations, all guided by…

Theaster Gates wears jumpsuit, shirt, and tie by PRADA.

What elevates a nondescript space into a work of art—and what ties it back to reality? Such queries bring Theaster Gates and Carsten Höller to the limits of imagination. The artists’ respective practices travel down paths that might appear divergent on the surface yet run parallel in the bigger vision. For Gates, histories become source material, bits and pieces of memories to finesse into revelations. The 52-year-old was born and raised in Chicago and studied urban planning and ceramics; today his conceptual practice encapsulates everything from public-involved artworks and architectural renovations to paintings, sculptures, and installations, all guided by his formidable creative intellect. For the last 15 years, he’s undertaken an ambitious plan to beat back the dilapidation of his hometown’s South Side with transformative real-estate initiatives largely under the umbrella of his keystone Rebuild Foundation.

Gates’ practice is generally linked with social engagement art, which, in theory, enacts real-life reform through projects with reach, and stakes, beyond the art world. In contrast, Höller’s reputation is enmeshed in relational aesthetics, a more esoteric, idealistic, and idiosyncratic counterpart. Born in Brussels to German parents, the artist earned a doctorate in agricultural science before chance exposure to the art scene intrigued him into a career pivot, one in which his inner child gets a say. Now 63, Höller is best known for the sort of sculptures that propel viewers through the air, as with his Flugmaschine (Flying Machine), 1996, or amid gigantic mushrooms, or through metal tubes, as with his beloved series of slide installations, a long-running project the artist feels has world-changing potential beyond its obvious use. Admittedly more understated are his olfactory-based works that tap into the poignant emotions associated with scent, including one that conjures the smells of his own late mother and father.

Carsten Höller wears jacket by PRADA.

Most conspicuously, the artists find common ground in how each turns spaces (lacking meaning) into places (of consequence), where action can and does happen, perhaps most notably in their different, extensive collaborations with Miuccia Prada. It follows that both espouse celebration: Gates’ large-scale Prada Mode installations frequently double as the backdrop for cultural exchange, from Abu Dhabi to Miami. And Höller hostsPrada Double Club pop-up nightclubs around the world; most recently, he staged a carnival-themed one in Los Angeles adjacent to Luna Luna. While Gates, who launched a three-year incubator, titled Dorchester Industries Experimental Design Lab, with the Prada Group in 2022, brainstorms community-centered programs out of his South Side headquarters, Höller, whose infamous slide still pokes out of Miuccia Prada’s three-story office, embraces high-concept entertaining with the likes of Brutalisten, his Brutalist-themed restaurant in Stockholm that opened in 2022. These days, both are in constant demand yet remain wellsprings of ideas. Last fall, Gates opened the Land School in a former South Side elementary school, while “Unto Thee” at the Smart Museum marks his first hometown solo museum exhibition. Abroad, Höller is revving up for presentations at Beijing’s UCCA Center for Contemporary Art and the 2026 Venice Biennale. Adapting to locales near and far is part of the two artists’ talent—a skill that arises from knowing how best to work with what’s right in front of you, wherever that may be.

Theaster wears jumpsuit, shirt, and tie by PRADA.

Theaster Gates: Your practice has been a light for me. You have the ability to change architecture toward sculpture; whereas for me, in some cases, I’m actually trying to leave sculpture completely. I’m trying my best to make a space something other than what it was, but it doesn’t always achieve sculpture. Sometimes it achieves emotion. I think that you have much more unity, which I admire.

Carsten Höller: I don’t think I have more unity. It’s just a slightly different approach. You have to make a distinction: If you make something that is an object (it can also be a performance or a film) or you enter an environment that surrounds your whole body, it’s not just a one-directional relationship. You are in a place, and it’s also about the other people who happen to be there. I think this holds true for your environments, too. Maybe I’m more mean than you are because I use people, and I want them to be seen by others who are there. Often people say to me, “I’ve seen one of your slides, but I didn’t take it.” You don’t have to take the slide, you can still see it as a sculpture in the classical sense. Your practice often makes people do things. They’re not just considering the meaning of an artwork, but they’re actually becoming participants. But in a slide, the idea is, you don’t do anything. You can’t. If you would be able to stop in it, it would be dangerous. The whole idea is about complete surrender.

Gates: I like the idea that a person can be an active participant in the work by just being present in a room. Regarding the buildings that I’m building and the spaces I’m renovating in Chicago, people often ask me, “What do your neighbors think?” I can’t know what’s on their minds, but I can say that they are actively contributing to the work with or without intention because they live next to me, because they walk down the street, because they have an opinion. That is part of the theater and the performance of an active neighborhood, of a sculpturally alive area.

Carsten wears jacket by PRADA.

Höller: It comes back to if the object is understood as finite. Most artworks have been like this, but in your case, the object is not finite because it just expands out of your control as the neighbors naturally become part of it. At the end of the day, I want to explore the possibilities of how things can be different. I’m strongly dissatisfied with the givenness of the world that I live in, with its expectations and problems. Maybe it’s just a reverie, but I would like to know what else there could be. Not only what else I could experience, but also how else, for instance, we could live together. I’m convinced that what we live in is just one possibility, something that has evolved, but it could be so much more. It could also be less. It could be different, for sure.

Gates: I studied ceramics in 2004 in a small town in Japan called Tokoname. I was invited to be a part of the Aichi Triennale in 2022, which celebrates the region. They offered me an old pottery factory, where they used to make ceramic sewer pipes. I decided to convert the family house into a jazz listening bar, a kissa. Tokoname is a city of potters—they didn’t need my sculpture. Rather than bringing something that would be absolutely familiar, I decided to do something that still used a spinning wheel, still needed my analog body, but that would be able to conjure something totally different. So I brought some turntables and for three months I played soul music from my personal collection every day. The city was excited to have a listening space. People would come, and they would sit and listen and watch me play. I had never experienced a situation where there was no alcohol, nothing for sale. It felt more like a religious experience, where all there was was observation and listening. It was still familiar but more sacred, more intimate. Music allowed me to do that.

Höller: There is a connection. You brought your own taste, your own culture. It’s not a physical object but an acoustic experience.

Gates: I was shocked that older Japanese men, who look like salarymen, would know all of the words of Roberta Flack or Aretha Franklin or Donny Hathaway. Even if they didn’t speak a lot of English, they knew the lyrics. I like that idea, that a thing can be both familiar and totally otherworldly.

Höller: The artworks that strike me most are the ones that have this dimension of creating a certain discomfort. Before I became an artist, I saw an artwork by Sigmar Polke: It was a pink painting, and there was a black corner. It looked really stupid. Then the title said, from knowing how best to work with what’s right in front of you, wherever that may be. Higher Beings Commanded: Paint the Upper-Right Corner Black! [1969]. I thought, How dare he? It’s also funny. At the same time, it’s very discomforting because you can’t place it. What results from that feeling is that you become confused. I like to work with confusion. I often call my work “confusion machines.” I don’t want to make a statement and then expect people to adhere to it. It is not about a certain outcome. It is about creating a situation where you have old Japanese men singing the words of their favorite musicians. Or the opposite: where you have people who go down a slide and think, I forget everything about who I am and what I do, and the only things I experience at this moment are two feelings, joy and fear. The middle ground is gone. The discomfort, the uncertainty, is a very good working tool because you can make beauty out of it. It’s not that you want people to feel strange—after this threshold of strangeness comes another thing that’s impossible to put in words.

Theaster wears jumpsuit, shirt, and tie by PRADA.

**Gates: **For me, hardship and joy live next to each other as comfortable partners. Race in America sometimes seems like 1940s Russia or something. Niceness was a survival tool for my parents, for my extended family, my grandparents. You had to toe the line of a certain niceness, or you could end up in a really precarious situation and maybe even death. So I’ve been conditioned for a long time to slide truth in with a bit of honey. The thing that I’m after is often complexly contentious. Maybe I’m angry about something. Maybe there are varying kinds of truths in the work, and what people see is minimalism. Or a friendly artist. Or a convivial moment. Both can be true at the same time.

Höller: Niceness and subversion go well together. I have seen that in your work.

Gates: Yes. There was a period around 2012 to 2015, where I felt the most radical in the things that I spoke out loud. I was giving lots of talks, and I was going to universities. I started to believe that my phone was tapped, that there were people in the audience who wereasking, “Why is he always talking about homelessness?” “Why is he always talking about the race issue?” “How does he imagine he has solutions?” I felt like a file was being kept on me like Malcolm X or Bob Dylan. In a way, I felt my life was in jeopardy because of a certain kind of rawness, a rawness that would be celebrated in France, Belgium, or the Netherlands. But in the States, there is room for character assassination, a stripping of your resources, some way of attacking. I found myself becoming much more subversive because I could feel strange political pressures around me. I felt very much in the tradition of somebody like [the late ex-Soviet-American artist]Ilya Kabakov.

Höller: The first time I saw you and your work was at Documenta 13 [in 2012].

Gates: It was exactly at that moment I felt like I could address them challenges that exist on the South Side of Chicago, or in certain neighborhoods. I used the opportunity to get 15 Black men to create a new vibe [in the performance 12 Ballads for Huguenot House]. Rather than talking about it, like, “Oh these men need a job,” it was, “No, we’re going to make some art. Let me show you how to use this system.”

**Höller: **When you do a strong work like this, how do you step out of its shadow? I do so many other things. The problem is that the ones that stick out are the slides, the mushrooms, the carousels. I do abstract paintings; I do invisible works, but nobody cares. I try, and I try, and I try, and I always fail.

Carsten wears jacket and pants by PRADA.

Gates: Right after Documenta, I joined White Cube. People were publicly disappointed that I would immediately align myself with one of the larger galleries in the market after doing what they felt was some kind of pinnacle of social engagement. But I went on to make one of my better exhibitions [“My Labor Is My Protest”] in London in Bermondsey in 2012. But you’re right, after Documenta, people were like, “Hey, why don’t you come to our museum and bring everybody...” I couldn’t do it, Carsten. I decided that I would try to build my painting practice, build my sculpture practice, and try to make an arc over time. I remember when I told my galleries, “My dad is dying.” He was a roofer, and I wanted to make these roofing paintings with him, and I wanted my next exhibition to be dedicated to them. And they said, “Why don’t you just make some more of those fire hoses? You know, they sell really well.” I said, “No, I have to make these for my dad.” Life was compelling me to move on and giving me new inspiration and new ideas in a new material. I was really excited, but they were very afraid that a buyer wouldn’t be ready for it. But that’s not my problem. You need those capstone moments in your career. Then you need to tell people, “Look, I’m not just the fucking mushroom guy.”

**Höller: **Many people want the mushrooms. I don’t mind. Same with the slides. I’m still making the slides myself. I always tell people, “You can do these slides without me. I’ll give the name of the company, the name of the guy to talk to.” I want the slides to be everywhere. I’m convinced they will change our world to some extent because they give us daily access to a moment of real madness. If you used a slide every day, you would be a different person. I spoke to Boris Johnson when they were building the Olympic Village in London, and I was trying to convince him to build a slide. But it didn’t happen. That’s the problem: It’s an art slide. Even if it goes somewhere like Miuccia Prada’s private office in Milan, it’s still an art slide. But it’s not just art. I remember when Miuccia asked me to do the show [“Synchro System,” 2000] for the Fondazione Prada. The space was free for a short amount of time from Christmas to New Year’s Eve between the men’s and women’s shows. I thought nobody would come, which is good because if nobody sees it, you can do whatever you like. But I was wrong. Many people saw it. I’m still meeting people who say, “I saw the show.” Upside Down Mushroom Room is now permanently installed in the new Fondazione Prada. After this we did these three Double Clubs that I liked very much because they were an intervention for real people at a real place. It was really massive, so I can say it was impactful.

Gates: Part of the reason that I continue to do projects with Prada is because it doesn’t end with the exhibition. I did this show called “True Value” [2016] where I bought a hardware store and delivered it to Fondazione Prada. Then I screened a video of the former owner and I talking about managing these objects, moving them around, and the life he had with his store, et cetera. So when I came to Milan, Miuccia set up a meeting for me to go visit hardware store owners. The old woman there told me how when she was a little girl, her father’s hardware store had been converted into a ration center during World War II. Then she and her son came to my exhibition. It was at that moment that I saw in Miuccia a person with an extremely sophisticated understanding of people and artists. There’s actually a relationship and curiosity.

Höller: I’m still good friends with Miuccia; we’re even now neighbors in Italy in the countryside... Theaster, there’s one thing you have to do. You have to come and visit me in Stockholm, and you have to eat with me at my restaurant [Brutalisten]. I insist.

**Gates: **Well Carsten, I think that I should come to Stockholm, and you should come to Chicago. We should have a permanent slide in Chicago. We have a room, and you can do anything you want.

Höller: Great, we have a plan.