’Hearts are meant to be broken" was written in De Profundis in 1897 by the imprisoned Oscar Wilde during his jail sentence at Reading Gaol in Surrey, England. Writers, philosophers and psychologists have indeed long warned that too much loving can only lead to profound heartbreak, since it is in human nature to abuse anything that is derived without a cost. Stamford Hospital, the debut novel by Thammika Songkaeo, published by Penguin Random House (Southeast Asia) in 2025, is a literary manifestation of this painful truism.

The book tells the story of Tarisa, a well-educated and solidly middle-class woman whose life is gravely affected by her unrelenting service of love. In marrying, the once academically adroit and ambitious thirty-something woman gives up her promising career. Sh…

’Hearts are meant to be broken" was written in De Profundis in 1897 by the imprisoned Oscar Wilde during his jail sentence at Reading Gaol in Surrey, England. Writers, philosophers and psychologists have indeed long warned that too much loving can only lead to profound heartbreak, since it is in human nature to abuse anything that is derived without a cost. Stamford Hospital, the debut novel by Thammika Songkaeo, published by Penguin Random House (Southeast Asia) in 2025, is a literary manifestation of this painful truism.

The book tells the story of Tarisa, a well-educated and solidly middle-class woman whose life is gravely affected by her unrelenting service of love. In marrying, the once academically adroit and ambitious thirty-something woman gives up her promising career. She migrates with Chris, her husband, to Singapore, as the man – extremely affluent as well as highly educated, like herself – chooses the city-state as their home because he had experienced discrimination in America, a country the nuptial couple had planned to live in permanently.

In the male-dominated and "homegrown" economy of Singapore, Tarisa is confined to mediocre jobs, changing sporadically from waitressing to pseudo-academic research under the supervision of discriminatory employers. Motherhood’s excruciating demands of childcare become overbearing, to the extent that she is close to the brink of destruction. Needing a room of her own, Tarisa checks Mia, her five-year-old daughter, into Stamford Hospital for medical assistance, despite the latter being barely sick. The book’s narrative is intricately unravelled with loneliness, sorrow and brutal reflections on the fragilities of life and the human condition, set over the course of two nights.

Thammika Songkaeo, a Singapore-based transnational writer of Thai origin and author of Stamford Hospital, speaks candidly about her novel with Life. The humid temperature, with sunny spells and mild monsoon rains, hit 32C when the following in-depth interview took place.

You have set your story in Singapore and in a hospital. Why did you choose Singapore rather than other cities such as Bangkok, London, Paris, New York, Shanghai or Tokyo? Is there a connection between Singapore and a hospital in terms of both being seen as clean, orderly or "hygienic" spaces?

As the main characters of Stamford Hospital are of Thai origin, I chose Singapore because I believe there are a great number of Thais living here. What I want to pursue in writing is, however, truth. I was not thinking about Singapore in comparison with other places because I believe you can write about truth in any setting. As for the hospital, I chose it because it is a venue of social care. Within this setting, where there is not much being said or done, a hospital can be an understated place to study the unspoken realities of mothers’ fatigue.

As for the question about a possible connection between Singapore and a hospital, the writing was not intended that way. However, any writer working with a hospital setting is likely to be subconsciously thinking about the concept of hygiene. I think it is beautiful if readers find a link between these two settings.

Your protagonist, Tarisa, is a well-educated, middle-class woman who moves across borders. She speaks multiple languages and is deeply interested in the arts. She is transnational, educated and cultured. However, beyond these attributes, she is also intelligent, sensitive and imaginative. In short, Tarisa personifies an exceptional human being. Yet what she receives in return for her dedication to love is heartbreaking. Do you feel you are being too strident in your portrayal of her? Relatedly, how did you create this character? Could you elaborate on what it took to bring her to life?

This is the first time I have been asked this question. It is a very powerful one. I don’t think I have come across anyone who has broken down Tarisa’s character in this way before. Some thoughts are coming to my mind. They may not be a direct answer to the question, but I am thinking them out loud with you. I think that although she is exceptional, there is nothing that can protect her from the harsh realities of the world. In fact, intelligent and compassionate people – those who are able to examine things from the widest possible angles – are often extremely sensitive because they have the deepest understanding of humanity. Their experiences of the world’s raucous realities, in this sense, are very raw and emotional.

What it took to do the job was a commitment to writing whenever inspiration struck. This included waking up at 3am when something important came from my subconscious. It also meant having a co-parent who would make sure our daughter was occupied and not coming into my room. I also needed to learn the skill of recognising when a writing wave was coming into my body and to be somatically in tune with myself. If I sensed the wave was coming, I had to write as soon as possible.

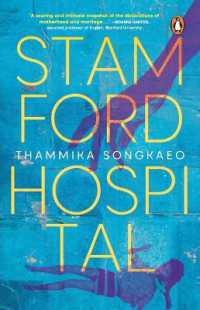

Stamford Hospital. photo courtesy of Stamford Hospital

In the novel, you write "Motherhood can be – not always, but it can be – the recipe for the destruction of a human being". This is a striking statement. Is this a viewpoint you still hold, or has it changed over time?

Fantastic question. It has changed, but not in a way that renders this understanding irrelevant. I think this statement – a deep study of motherhood – still applies to many people and will always apply. It is a statement that can be considered permanently true.

However, my viewpoint has evolved. I have come to understand that motherhood, even when it moves through a river of destruction, is also part of the creation of the strongest women. I have learnt this truth through my own experience.

Right now, my daughter is nine years old. When I wrote Stamford Hospital, she was about three, an especially demanding age and a very tiring period for me. I am now working on my second book. Motherhood is still the theme, but I am approaching it as a form of strength.

Regarding your deuteragonist, Chris, in the book, he constantly refuses to have sex with his wife, yet at the end we discover that he engages in abominable behaviour. The novel’s narrative moves persuasively from a mother’s psychological disorder to a story of deceit. While I can understand Tarisa’s raison d’être in rejecting motherhood, is there anything that helps readers understand Chris’s repulsive character? The British-Pakistani author Hanif Kureishi deals convincingly with the complex realities that lead to the breakdown of masculinity. You share a similar depth of insight into womanhood.

It is a piercing question that asks writers to be sensitive. You feel that there are things to be said about this character, but the protagonist has not yet represented him in his deepest, most characteristic form. The ways in which Chris harms Tarisa can be examined, but they are left unspoken at this stage because she is still in the process of justifying those harms and learning how he inflicts them upon her.

You quote Socrates – "the unexamined life is not worth living". Towards the end, Tarisa sits down to reflect on her life and discovers her identity. However, Socrates was esoteric and difficult to understand. It was only through the more accessible works of his student, Plato, that later readers came to appreciate the significance of his thinking. Socrates’ ideas were largely directed at the intelligentsia, the elites. Tarisa is able to examine her life because she is well educated and, consequently, financially secure. But I am concerned that a large portion of the general public cannot afford this privilege. How important is it for you to move beyond the world of elite education and wealth?

That is an important question, as it asks about the social place of reading and writing. I do not have a direct answer, but I think Tarisa’s story offers an opportunity for us to question what it means to be "elite" and to understand how fragile that eliteness can be. One could argue that if Tarisa were to leave her marriage, she would probably lose financial security, as she is dependent on her husband. But if she chooses to stay, she must endure an unhappy marriage. This points to the fragility of one’s chosen condition and the cost of holding on to it.

I agree that training is often needed to learn how to break things down and examine life critically. But if Tarisa were to leave her marriage, would she continue to examine things in this way? I think she would, because this quality is part of her character. Yes, Tarisa is able to examine her life because she is well educated, but I would also say that qualities such as curiosity help people to learn, and that learning itself is always worthwhile.

You spoke openly that a manuscript of Stamford Hospital was rejected over a hundred times by publishers. How did this experience shape you as a writer? Do you have a message to aspiring writers?

It shaped me positively, even though it was terrible to receive so many rejections and feel that you were getting nowhere. But what came out of it was this: since I knew they were going to reject me anyway, I might as well take the time to write a book that was truly me and one that I ended up loving. I was not writing to draw attention from anyone.

I have deep empathy for writers who are receiving so many rejections. It is their time to become truly good.

I know that authors usually keep quiet about their next book, but since you have briefly touched on it, is there anything you would like to share with us that might give a sense of what we can expect from your forthcoming work?

I actually spoke very little about it. In an article about me in a leading social and cultural magazine that came out late last year, I began to mention a daughter who chooses to break a cycle of unhealthy family dynamics. I am still in the process of expanding this idea, but I will reiterate it with you.

The work is about a strong woman who has gone through so much in life. She finally decides that not only is she in a position to make her own life better, but she is also able to shape how to live for her daughter. She makes some extremely difficult decisions and tells her daughter that these are hard decisions, but they are right and must be made accordingly.

The book is about a mother and a daughter – the same character who plays out all these different roles – who comes to be adamant that she wants to decide her own future.

Sawarin Suwichakornpong divides her time between Bangkok, Phuket and London. She was a part-time book reviewer for the Bangkok Post between 2013 and 2021.