In this article, you will learn what data leakage is, how it silently inflates model performance, and practical patterns for preventing it across common workflows.

Topics we will cover include:

- Identifying target leakage and removing target-derived features.

- Preventing train–test contamination by ordering preprocessing correctly.

- Avoiding temporal leakage in time series with proper feature design and splits.

Let’s get started.

3 Subtle Ways Data Leakage Can Ruin Your Models (and How to Prevent It) Image by Editor

Introduction

Data leakage is an often accidental problem that may happen in machine lear…

In this article, you will learn what data leakage is, how it silently inflates model performance, and practical patterns for preventing it across common workflows.

Topics we will cover include:

- Identifying target leakage and removing target-derived features.

- Preventing train–test contamination by ordering preprocessing correctly.

- Avoiding temporal leakage in time series with proper feature design and splits.

Let’s get started.

3 Subtle Ways Data Leakage Can Ruin Your Models (and How to Prevent It) Image by Editor

Introduction

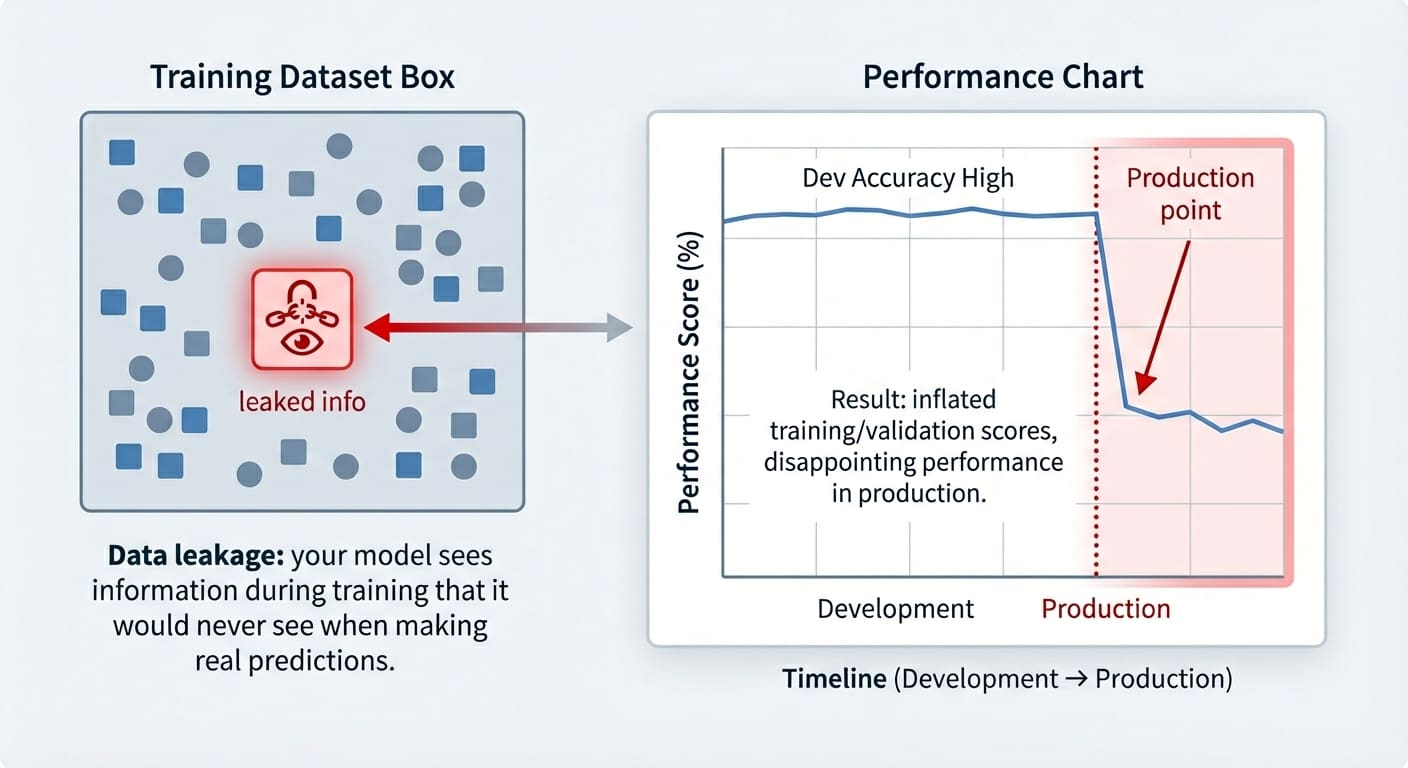

Data leakage is an often accidental problem that may happen in machine learning modeling. It happens when the data used for training contains information that “shouldn’t be known” at this stage — i.e. this information has leaked and become an “intruder” within the training set. As a result, the trained model has gained a sort of unfair advantage, but only in the very short run: it might perform suspiciously well on the training examples themselves (and validation ones, at most), but it later performs pretty poorly on future unseen data.

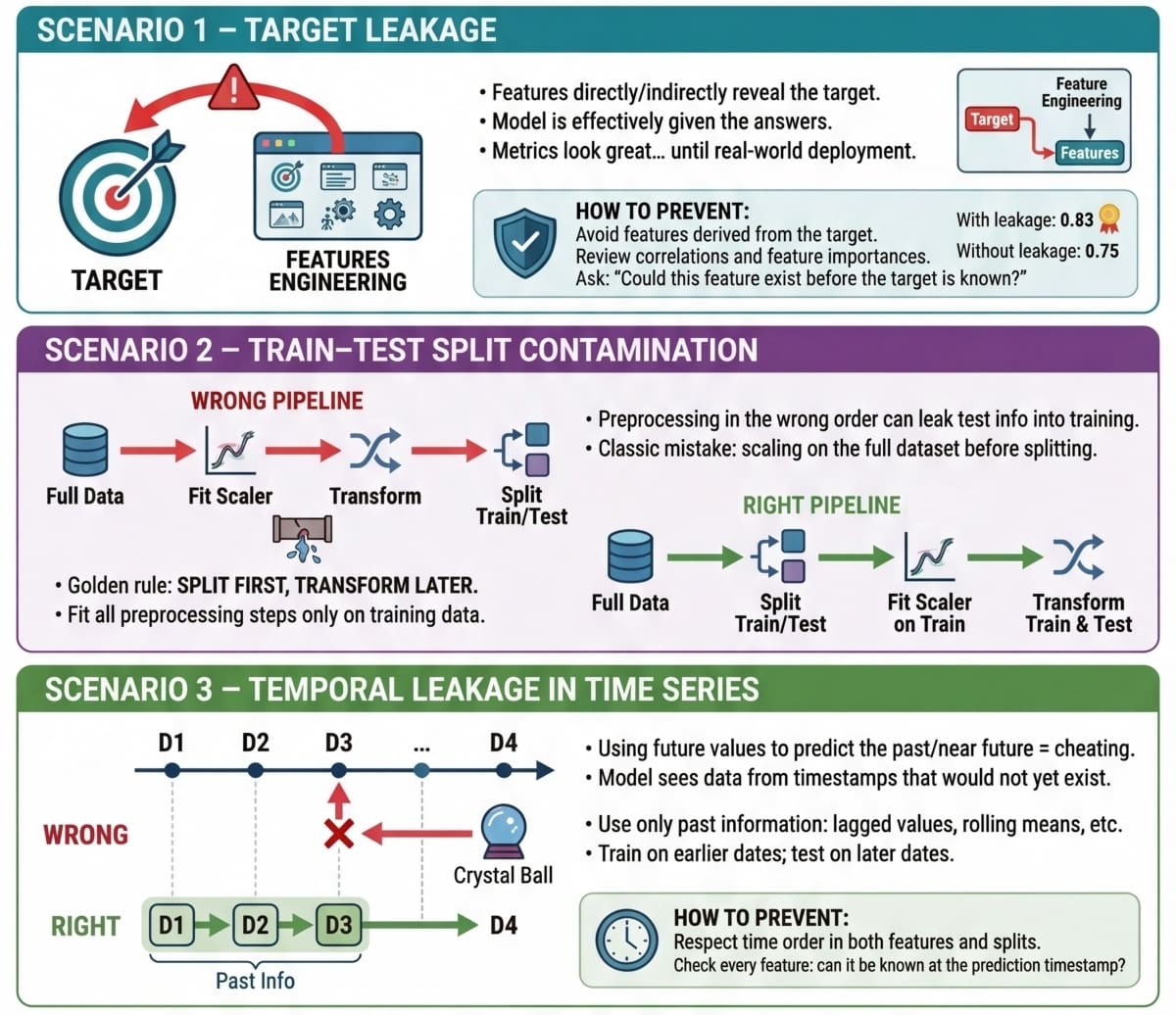

This article shows three practical machine learning scenarios in which data leakage may happen, highlighting how it affects trained models, and showcasing strategies to prevent this issue in each scenario. The data leakage scenarios covered are:

- Target leakage

- Train-test split contamination

- Temporal leakage in time series data

Data Leakage vs. Overfitting

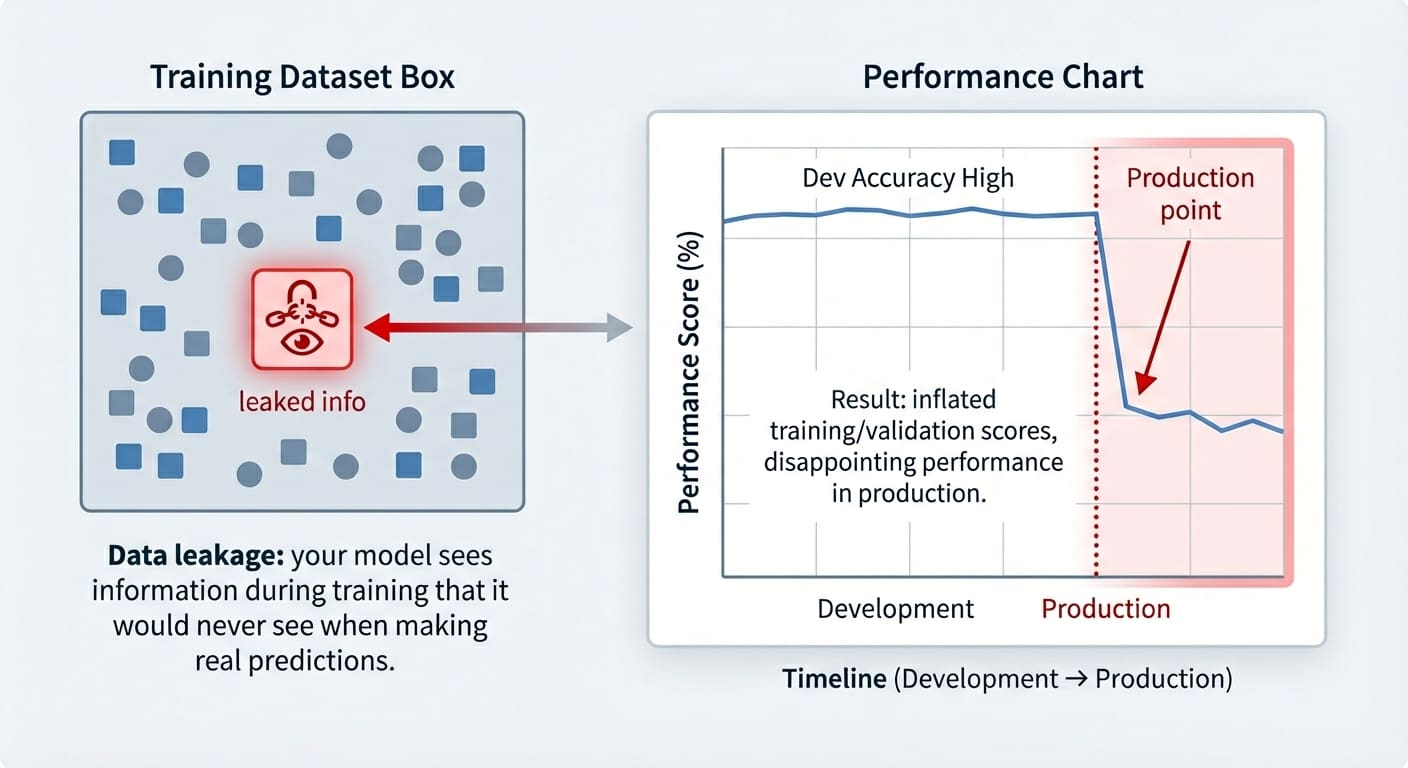

Even though data leakage and overfitting can produce similar-looking results, they are different problems.

Overfitting arises when a model memorizes overly specific patterns from the training set, but the model is not necessarily receiving any illegitimate information it shouldn’t know at the training stage — it is just learning excessively from the training data.

Data leakage, by contrast, occurs when the model is exposed to information it should not have during training. Moreover, while overfitting typically arises as a poorly generalizing model on the validation set, the consequences of data leakage may only surface at a later stage, sometimes already in production when the model receives truly unseen data.

Data leakage vs. overfitting Image by Editor

Let’s take a closer look at 3 specific data leakage scenarios.

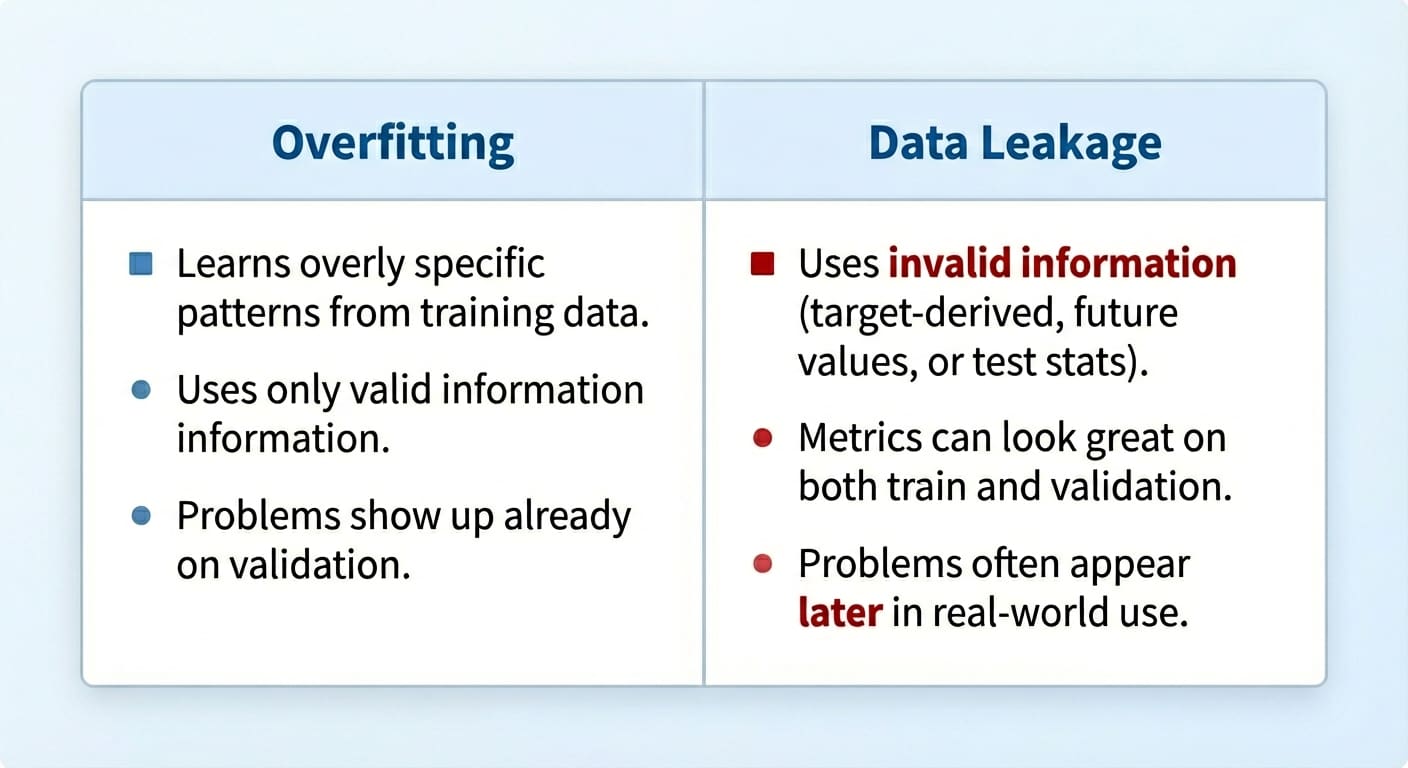

Scenario 1: Target Leakage

Target leakage occurs when features contain information that directly or indirectly reveals the target variable. Sometimes this can be the result of a wrongly applied feature engineering process in which target-derived features have been introduced in the dataset. Passing training data containing such features to a model is comparable to a student cheating on an exam: part of the answers they should come up with by themselves has been provided to them.

The examples in this article use scikit-learn, Pandas, and NumPy.

Let’s see an example of how this problem may arise when training a dataset to predict diabetes. To do so, we will intentionally incorporate a predictor feature derived from the target variable, 'target' (of course, this issue in practice tends to happen by accident, but we are injecting it on purpose in this example to illustrate how the problem manifests!):

| 1234567891011121314151617181920 | from sklearn.datasets import load_diabetesimport pandas as pdimport numpy as npfrom sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegressionfrom sklearn.model_selection import train_test_splitX, y = load_diabetes(return_X_y=True, as_frame=True)df = X.copy()df[‘target’] = (y > y.median()).astype(int) # Binary outcome# Add leaky feature: related to the target but with some random noisedf[‘leaky_feature’] = df[‘target’] + np.random.normal(0, 0.5, size=len(df))# Train and test model with leaky featureX_leaky = df.drop(columns=[‘target’])y = df[‘target’]X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X_leaky, y, random_state=0, stratify=y)clf = LogisticRegression(max_iter=1000).fit(X_train, y_train)print("Test accuracy with leakage:", clf.score(X_test, y_test)) |

Now, to compare accuracy results on the test set without the “leaky feature”, we will remove it and retrain the model:

| 12345 | # Removing leaky feature and repeating the processX_clean = df.drop(columns=[‘target’, ‘leaky_feature’])X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X_clean, y, random_state=0, stratify=y)clf = LogisticRegression(max_iter=1000).fit(X_train, y_train)print("Test accuracy without leakage:", clf.score(X_test, y_test)) |

You may get a result like:

| 12 | Test accuracy with leakage: 0.8288288288288288Test accuracy without leakage: 0.7477477477477478 |

Which makes us wonder: wasn’t data leakage supposed to ruin our model, as the article title suggests? In fact, it is, and this is why data leakage can be difficult to spot until it might be late: as mentioned in the introduction, the problem often manifests as inflated accuracy both in training and in validation/test sets, with the performance downfall only noticeable once the model is exposed to new, real-world data. Strategies to prevent it ideally include a combination of steps like carefully analyzing correlations between the target and the rest of the features, checking feature weights in a newly trained model and seeing if any feature has an overly large weight, and so on.

Scenario 2: Train-Test Split Contamination

Another very frequent data leakage scenario often arises when we don’t prepare the data in the right order, because yes, order matters in data preparation and preprocessing. Specifically, scaling the data before splitting it into training and test/validation sets can be the perfect recipe to accidentally (and very subtly) incorporate test data information — through the statistics used for scaling — into the training process.

These quick code excerpts based on the popular wine dataset show the wrong vs. right way to apply scaling and splitting (it’s a matter of order, as you will notice!):

| 12345678910111213141516 | import pandas as pdfrom sklearn.datasets import load_winefrom sklearn.model_selection import train_test_splitfrom sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScalerfrom sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegressionX, y = load_wine(return_X_y=True, as_frame=True)# WRONG: scaling the full dataset before splitting may cause leakagescaler = StandardScaler().fit(X)X_scaled = scaler.transform(X)X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X_scaled, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=42, stratify=y)clf = LogisticRegression(max_iter=2000).fit(X_train, y_train)print("Accuracy with leakage:", clf.score(X_test, y_test)) |

The right approach:

| 12345678 | X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=42, stratify=y)scaler = StandardScaler().fit(X_train) # the scaler only "learns" from training data...X_train_scaled = scaler.transform(X_train)X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test) # ... but, of course, it is applied to both partitionsclf = LogisticRegression(max_iter=2000).fit(X_train_scaled, y_train)print("Accuracy without leakage:", clf.score(X_test_scaled, y_test)) |

Depending on the specific problem and dataset, applying the right or wrong approach will make little or no difference because sometimes the test-specific leaked information may statistically be very similar to that in the training data. Do not take this for granted in all datasets and, as a matter of good practice, always split before scaling.

Scenario 3: Temporal Leakage in Time Series Data

The last leakage scenario is inherent to time series data, and it occurs when information about the future — i.e. information to be forecasted by the model — is somehow leaked into the training set. For example, using future values to predict past ones in a stock pricing scenario is not the right approach to build a forecasting model.

This example considers a synthetically generated small dataset of daily stock prices, and we intentionally add a new predictor variable that leaks in information about the future that the model shouldn’t be aware of at training time. Again, we do this on purpose here to illustrate the issue, but in real-world scenarios this is not too rare to happen due to factors like inadvertent feature engineering processes:

| 1234567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132 | import pandas as pdimport numpy as npfrom sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegressionnp.random.seed(0)dates = pd.date_range("2020-01-01", periods=300)# Synthetic data generation with some patterns to introduce temporal predictabilitytrend = np.linspace(100, 150, 300) seasonality = 5 * np.sin(np.linspace(0, 10*np.pi, 300)) # Autocorrelated small noise: previous day data partly influences next daynoise = np.random.randn(300) * 0.5 for i in range(1, 300): noise[i] += 0.7 * noise[i-1]prices = trend + seasonality + noisedf = pd.DataFrame({"date": dates, "price": prices})# WRONG CASE: introducing leaky feature (next-day price)df[‘future_price’] = df[‘price’].shift(-1)df = df.dropna(subset=[‘future_price’])X_leaky = df[[‘price’, ‘future_price’]]y = (df[‘future_price’] > df[‘price’]).astype(int)X_train, X_test = X_leaky.iloc[:250], X_leaky.iloc[250:]y_train, y_test = y.iloc[:250], y.iloc[250:]clf = LogisticRegression(max_iter=500)clf.fit(X_train, y_train)print("Accuracy with leakage:", clf.score(X_test, y_test)) |

If we wanted to enrich our time series dataset with new, meaningful features for better prediction, the right approach is to incorporate information describing the past, rather than the future. Rolling statistics are a great way to do this, as shown in this example, which also reformulates the predictive task into classification instead of numerical forecasting:

| 1234567891011121314151617 | # New target: next-day direction (increase vs decrease)df[‘target’] = (df[‘price’].shift(-1) > df[‘price’]).astype(int)# Added feature related to the past: 3-day rolling meandf[‘rolling_mean’] = df[‘price’].rolling(3).mean()df_clean = df.dropna(subset=[‘rolling_mean’, ‘target’])X_clean = df_clean[[‘rolling_mean’]]y_clean = df_clean[‘target’]X_train, X_test = X_clean.iloc[:250], X_clean.iloc[250:]y_train, y_test = y_clean.iloc[:250], y_clean.iloc[250:]from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegressionclf = LogisticRegression(max_iter=500)clf.fit(X_train, y_train)print("Accuracy without leakage:", clf.score(X_test, y_test)) |

Once again, you may see inflated results for the wrong case, but be warned: things may turn upside down once in production if there was impactful data leakage along the way.

Data leakage scenarios summarized Image by Editor

Wrapping Up

This article showed, through three practical scenarios, some forms in which data leakage may manifest during machine learning modeling processes, outlining their impact and strategies to navigate these issues, which, while apparently harmless at first, may later wreak havoc (literally!) while in production.

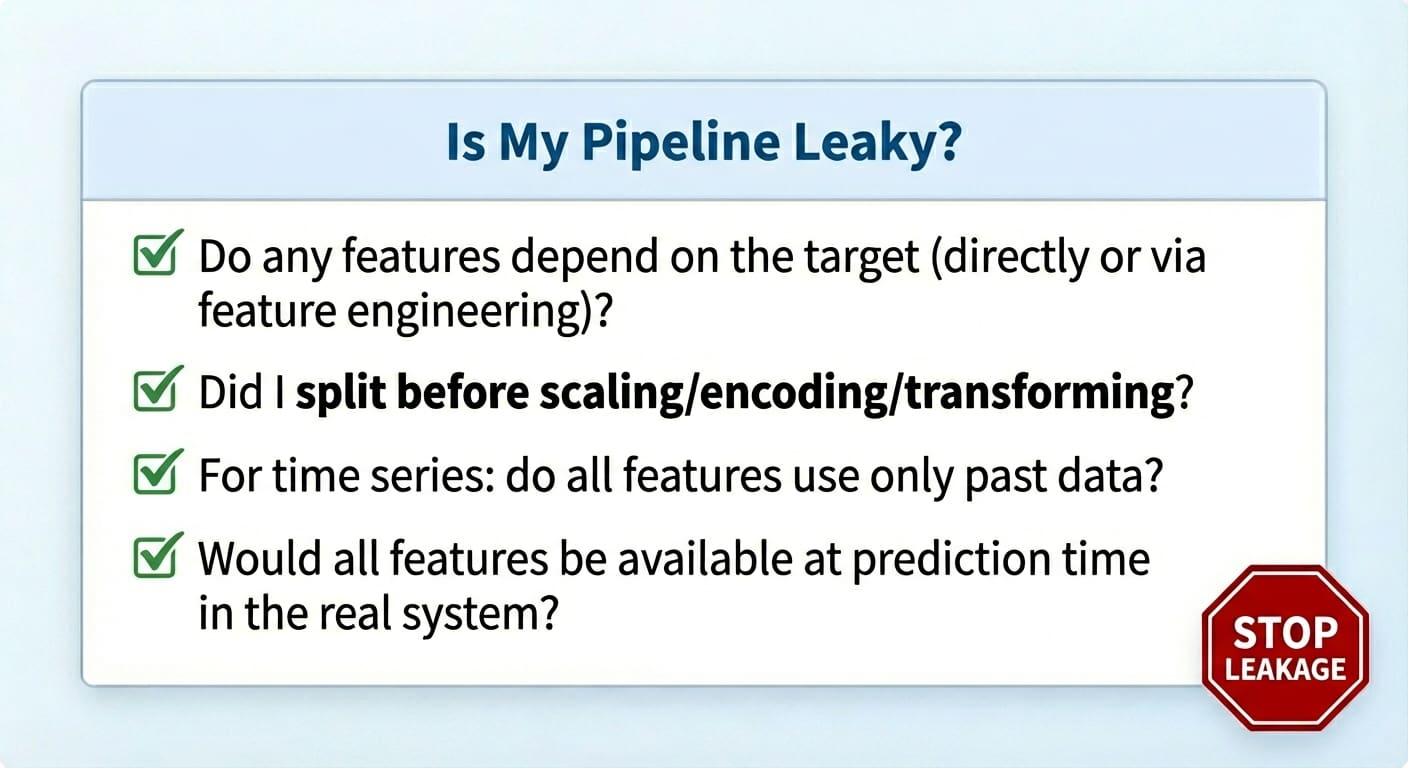

Data leakage checklist Image by Editor