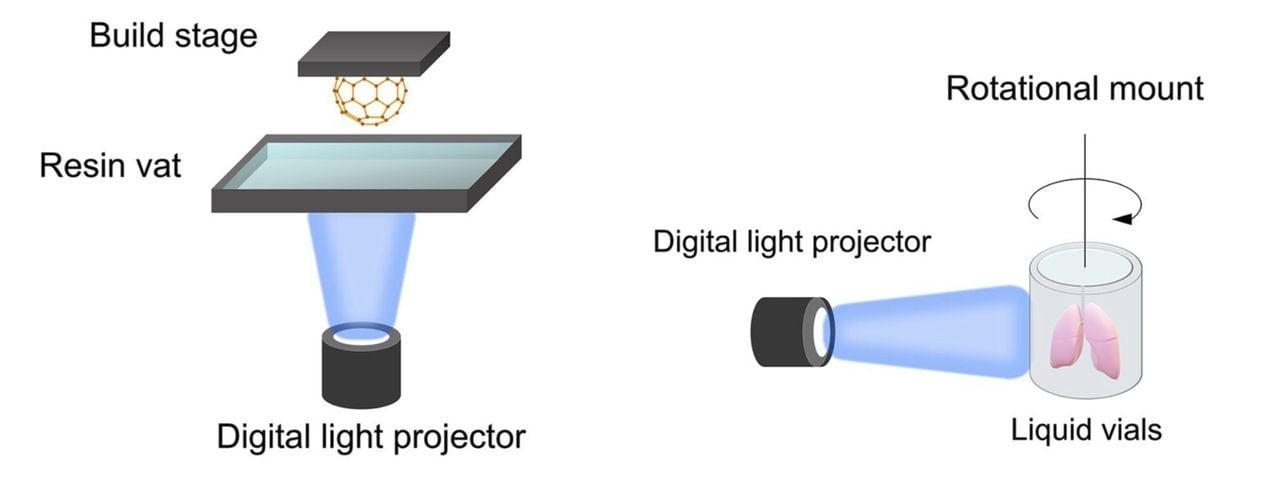

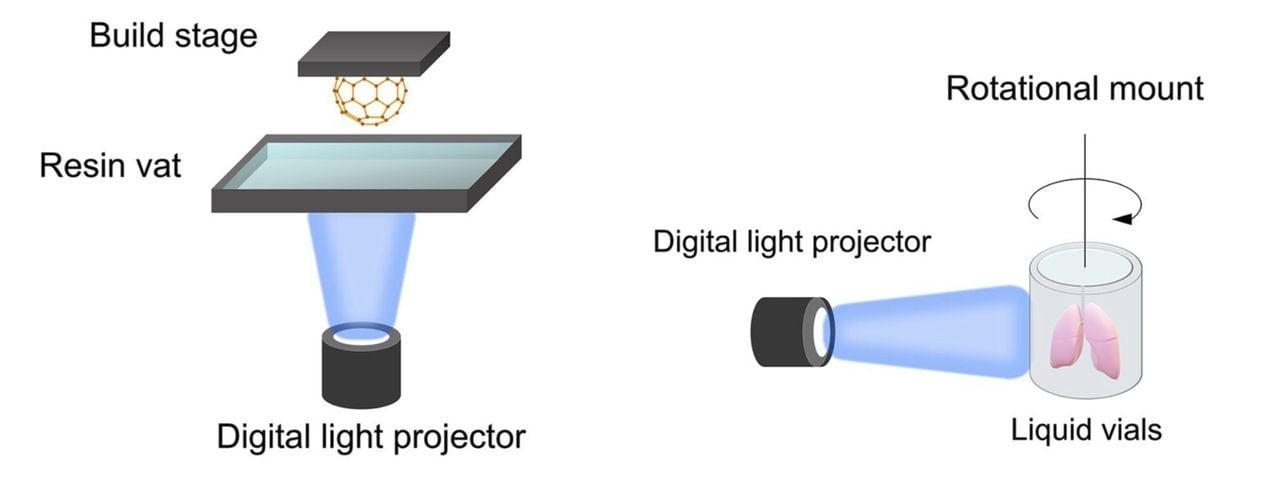

Conventional (left) resin 3D printing versus volumetric resin 3D printing [Source: Taylor & Francis]

Conventional (left) resin 3D printing versus volumetric resin 3D printing [Source: Taylor & Francis]

A new review of volumetric additive manufacturing outlines rapid progress, persistent constraints, and the milestones needed for broader deployment.

Volumetric approaches invert the usual layer paradigm by shaping a 3D light field that polymerizes a part throughout a liquid volume at once. The best known variants are Computed Axial Lithography (CAL), which projects tomographic patterns into a rotating vat, and xolography, which uses intersecting light fields and specialized photochemistry to trigger curing only where beams overlap. Compared with conventional vat photopolymerization, volumetric p…

Conventional (left) resin 3D printing versus volumetric resin 3D printing [Source: Taylor & Francis]

Conventional (left) resin 3D printing versus volumetric resin 3D printing [Source: Taylor & Francis]

A new review of volumetric additive manufacturing outlines rapid progress, persistent constraints, and the milestones needed for broader deployment.

Volumetric approaches invert the usual layer paradigm by shaping a 3D light field that polymerizes a part throughout a liquid volume at once. The best known variants are Computed Axial Lithography (CAL), which projects tomographic patterns into a rotating vat, and xolography, which uses intersecting light fields and specialized photochemistry to trigger curing only where beams overlap. Compared with conventional vat photopolymerization, volumetric printing targets seconds to minutes per build, inherently supportless geometry, and fully enclosed cavities.

The paper situates this family of processes alongside mainstream vat photopolymerization, Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), and continuous DLP, emphasizing where volumetric shines: isotropic properties due to near-simultaneous cure, minimal post processing, and potential for biocompatible hydrogels. It also catalogs early systems from research labs and startups that have demonstrated centimeter scale parts and living-tissue constructs, building on well publicized work from LLNL and academic collaborators on CAL, as well as commercial experiments in tomographic biofabrication.

How Volumetric Printing Works

At its core, volumetric AM solves an inverse problem: compute a sequence or field of projections that accumulates dose to just exceed a resin’s cure threshold inside the desired solid and remain subthreshold elsewhere. In CAL, an algorithm akin to filtered back projection or iterative algebraic methods calculates grayscale patterns that, as the vat rotates, integrate to the target dose distribution. Xolography, by contrast, leverages two photon activation chemistry or dual wavelength initiators so that only the intersection of beams sees the effective dose rate.

This places unusual demands on materials and optics. Resins need predictable attenuation, low scattering, and sharp threshold behavior to maintain spatial selectivity. High dynamic range, high power projection is required to deliver adequate energy through the build volume without overheating or overcuring. Computation is nontrivial, too; accurate forward models of resin kinetics and diffusion improve fidelity but add processing time, pushing vendors toward GPU acceleration and model based correction.

Speed Promises, Real Constraints

The review is positive on throughput, but also careful with some gotchas. Demonstrations often show several centimeter scale parts produced in under a minute, yet that is with optically tuned resins in small build volumes. As parts get larger or more opaque, available light intensity becomes the bottleneck, and dose gradients blur features. Reported resolutions are typically on the order of tens to hundreds of microns, with surface detail and sharp edges the first to suffer when scattering rises.

Materials remain the biggest limiter. Beyond acrylate and epoxy photopolymers, researchers have shown promising suspensions for ceramics and even silica precursors, followed by debinding and sintering, but those are still exploratory and sensitive to optical turbidity. Hydrogels are an active bright spot for biofabrication, trading resolution for gentle, fast encapsulation of cells. For industrial parts, the path to durable, heat resistant resins compatible with volumetric optics is still being paved.

Automation and quality assurance also lag. Support removal is largely moot, but reliable part release, resin recirculation, in situ dosimetry, and closed loop correction are not solved at product level. Unlike layer based systems that benefit from per layer inspection, volumetric processes need volumetric sensing or robust physics models to guarantee dimensional accuracy. The review notes that standardized benchmarks, mechanical datasets, and fatigue results are sparse.

Where It Could Land First

Near term adopters are likely labs and medical researchers producing bespoke hydrogel constructs, microfluidic devices, or optical components where supportless internal channels are critical. Design studios may tap volumetric printers for fast concept models with intricate voids. Service bureaus and automotive or dental users will want proof of repeatability, rugged materials, and clear economics before committing; energy use, consumables, and failure modes are not yet well quantified.

What to watch next: better resin toolkits with tailored attenuation and threshold kinetics, integrated dosimetry for closed loop exposure, and credible comparisons against DLP and SLS on identical geometries. If vendors can publish end to end build time, yield, and mechanical data on parts beyond a few centimeters, the conversation will move from promise to planning.

If you are interested in learning more about volumetric AM, this paper provides a very extensive overview with plenty of diagrams to explain the various approaches used today.

Via Taylor & Francis