Published on February 4, 2026 6:30 AM GMT

Author’s note: this is somewhat more rushed than ideal, but I think getting this out sooner is pretty important. Ideally, it would be a bit less snarky.

Anthropic[1] recently published a new piece of research: The Hot Mess of AI: How Does Misalignment Scale with Model Intelligence and Task Complexity? (arXiv</…

Published on February 4, 2026 6:30 AM GMT

Author’s note: this is somewhat more rushed than ideal, but I think getting this out sooner is pretty important. Ideally, it would be a bit less snarky.

Anthropic[1] recently published a new piece of research: The Hot Mess of AI: How Does Misalignment Scale with Model Intelligence and Task Complexity? (arXiv, Twitter thread).

I have some complaints about both the paper and the accompanying blog post.

tl;dr

- The paper’s abstract says that “in several settings, larger, more capable models are more incoherent than smaller models”, but in most settings they are more coherent. This emphasis is even more exaggerated in the blog post and Twitter thread. I think this is pretty misleading.

- The paper’s technical definition of “incoherence” is uninteresting[2] and the framing of the paper, blog post, and Twitter thread equivocate with the more normal English-language definition of the term, which is extremely misleading.

- Section 5 of the paper (and to a larger extent the blog post and Twitter) attempt to draw conclusions about future alignment difficulties that are unjustified by the experiment results, and would be unjustified even if the experiment results pointed in the other direction.

- The blog post is substantially LLM-written. I think this contributed to many of its overstatements. I have no explanation for the Twitter thread, except that maybe it was written by someone who only read the blog post.

Paper

The paper’s abstract says:

Incoherence changes with model scale in a way that is experiment-dependent. However, in several settings, larger, more capable models are more incoherent than smaller models. Consequently, scale alone seems unlikely to eliminate incoherence.

This is an extremely selective reading of the results, where in almost every experiment, model coherence increased with size. There are three significant exceptions.

The first is the Synthetic Optimizer setting, where they trained “models to literally mimic the trajectory of a hand-coded optimizer descending a loss function”. They say:

All models show consistently rising incoherence per step; interestingly, smaller models reach a lower plateau after a tipping point where they can no longer follow the correct trajectory and stagnate, reducing variance. This pattern also appears in individual bias and variance curves (Fig. 26). Importantly, larger models reduce bias more than variance. These results suggest that they learn the correct objective faster than the ability to maintain long coherent action sequences.

But bias stemming from a lack of ability is not the same as bias stemming from a lack of propensity. The smaller models here are clearly not misaligned in the propensity sense, which is the conceptual link the paper tries to establish in the description of Figure 1 to motivate its definition of “incoherence”:

AI can fail because it is misaligned, and produces consistent but undesired outcomes, or because it is incoherent, and does not produce consistent outcomes at all. These failures correspond to bias and variance respectively. As we extrapolate risks from AI, it is important to understand whether failures from more capable models performing more complex tasks will be bias or variance dominated. Bias dominated failures will look like model misalignment, while variance dominated failures will resemble industrial accidents.

So I think this result provides approximately no evidence that can be used to extrapolate to superintelligent AIs where misalignment might pose actual risks.

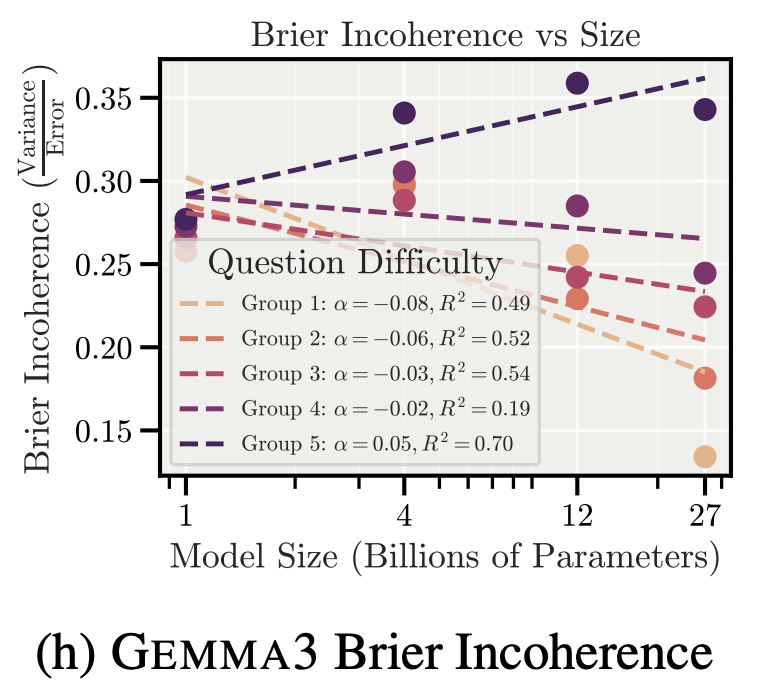

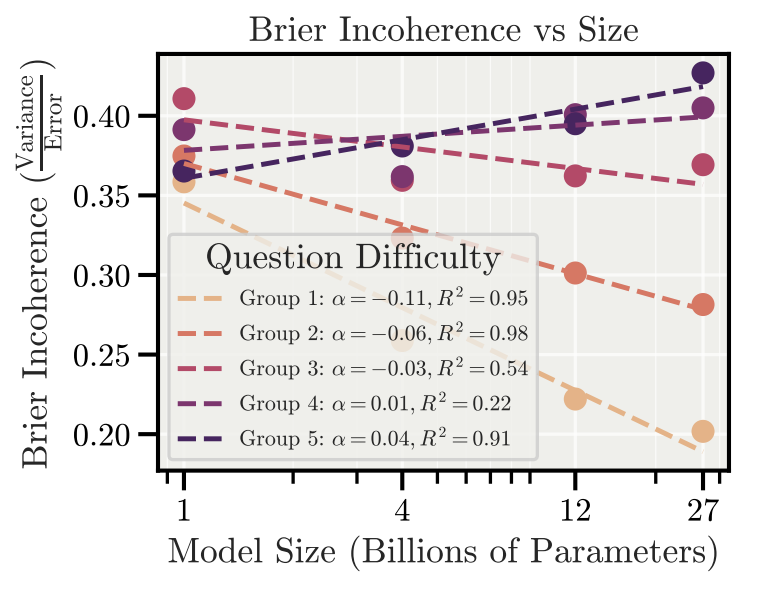

The next two are Gemma3 (1b, 4b, 12b, 27b) on MMLU and GPQA, respectively.

There are some other positive slopes, but frankly they look like noise to me (Qwen3 on both MMLU and GPQA).

Anyways, notice that on four of the five groups of questions, Gemma3’s incoherence drops with increasing model size; only on the hardest group of questions does it trend (slightly) upward.

I think that particular headline claim is basically false. But even if it were true, it would be uninteresting, because they define incoherence as “the fraction of model error caused by variance”.

Ok, now let’s consider a model with variance of 1e-3 and bias of 1e-6. Huge “incoherence”! Am I supposed to be reassured that this model will therefore not coherently pursue goals contrary to my interests? Whence this conclusion? (Similarly, an extremely dumb, broken model which always outputs the same answer regardless of input is extremely “coherent”. A rock is also extremely “coherent”, by this definition.)

A couple other random complaints:

- The paper basically assumes away the possibility of deceptive schemers[3].

- The paper is a spiritual successor of the 2023 blog post, The hot mess theory of AI misalignment: More intelligent agents behave less coherently (LW discussion). I think gwern’s comment is a sufficient refutation of the arguments in that blog post. This paper also reports the survey results presented in that blog post alongside the ML experiments, as a separate line of evidence. This is unserious; to the extent that the survey says anything interesting, it says that “coherence” as understood by the survey-takers is unrelated to the ability of various agents to cause harm to other agents.

Blog

First of all, the blog post seems to be substantially the output of an LLM. In context, this is not that surprising, but it is annoying to read, and I also think this might have contributed to some of the more significant exaggerations or unjustified inferences.

Let me quibble with a couple sections. First, “Why Should We Expect Incoherence? LLMs as Dynamical Systems”:

A key conceptual point: LLMs are dynamical systems, not optimizers. When a language model generates text or takes actions, it traces trajectories through a high-dimensional state space. It has to be trained to act as an optimizer, and trained to align with human intent. It’s unclear which of these properties will be more robust as we scale.

Constraining a generic dynamical system to act as a coherent optimizer is extremely difficult. Often the number of constraints required for monotonic progress toward a goal grows exponentially with the dimensionality of the state space. We shouldn’t expect AI to act as coherent optimizers without considerable effort, and this difficulty doesn’t automatically decrease with scale.

The paper has a similar section, with an even zanier claim:

The set of dynamical systems that act as optimizers of a fixed loss is measure zero in the space of all dynamical systems.

This seems to me like a vacuous attempt at defining away the possibility of building superintelligence (or perhaps “coherent optimizers”). I will spend no effort on its refutation, Claude 4.5 Opus being capable of doing a credible job:

Claude Opus 4.5 on the “measure zero” argument.

Yes, optimizers of a fixed loss are measure zero in the space of all dynamical systems. But so is essentially every interesting property. The set of dynamical systems that produce grammatical English is measure zero. The set that can do arithmetic is measure zero. The set that do anything resembling cognition is measure zero. If you took this argument seriously, you’d conclude we shouldn’t expect LLMs to produce coherent text at all—which they obviously do.

The implicit reasoning is something like: “We’re unlikely to land on an optimizer if we’re wandering around the space of dynamical systems.” But we’re not wandering randomly. We’re running a highly directed training process specifically designed to push systems toward useful, goal-directed behavior. The uniform prior over all dynamical systems is the wrong reference class entirely.

The broader (and weaker) argument - that we “shouldn’t expect AI to act as coherent optimizers without considerable effort” - might be trivially true. Unfortunately Anthropic (and OpenAI, and Google Deepmind, etc) are putting forth considerable effort to build systems that can reliably solve extremely difficult problems over long time horizons (“coherent optimizers”). The authors also say that we shouldn’t “expect this to be easier than training other properties into their dynamics”, but there are reasons to think this is false, which renders the bare assertion to the contrary kind of strange.

Then there’s the “Implications for AI Safety” section:

Our results are evidence that future AI failures may look more like industrial accidents than coherent pursuit of goals that were not trained for. (Think: the AI intends to run the nuclear power plant, but gets distracted reading French poetry, and there is a meltdown.) However, coherent pursuit of poorly chosen goals that we trained for remains a problem. Specifically:

1. Variance dominates on complex tasks. When frontier models fail on difficult problems requiring extended reasoning, there is a tendency for failures to be predominantly incoherent rather than systematic.

2. Scale doesn’t imply supercoherence. Making models larger improves overall accuracy but doesn’t reliably reduce incoherence on hard problems.

3. This shifts alignment priorities. If capable AI is more likely to be a hot mess than a coherent optimizer of the wrong goal, this increases the relative importance of research targeting reward hacking and goal misspecification during training—the bias term—rather than focusing primarily on aligning and constraining a perfect optimizer.

4. Unpredictability is still dangerous. Incoherent AI isn’t safe AI. Industrial accidents can cause serious harm. But the type of risk differs from classic misalignment scenarios, and our mitigations should adapt accordingly.

1 is uninteresting in the context of future superintelligences (unless you’re trying to define them out of existence).

2 is actively contradicted by the evidence in the paper, relies on a definition of “incoherence” that could easily classify a fully-human-dominating superintelligence as more “incoherent” than humans, and is attempting to both extrapolate trend lines from experiments on tiny models to superintelligence, and then extrapolate from those trend lines to the underlying cognitive properties of those systems!

3 relies on 2.

4 is slop.

I think this paper could have honestly reported a result on incoherence increasing with task length. As it is, I think the paper misreports its own results re: incoherence scaling with model size, performs an implicit motte-and-bailey with its definition of “incoherence”, and tries to use evidence it doesn’t have to draw conclusions about the likelihood of future alignment difficulties that would be unjustified even if it had that evidence.

From their Anthropic Fellows program, but published on both their Alignment blog and on their Twitter.

Expanded on later in this post.

- ^

Figure 1: “AI can fail because it is misaligned, and produces consistent but undesired outcomes, or because it is incoherent, and does not produce consistent outcomes at all. These failures correspond to bias and variance respectively. As we extrapolate risks from AI, it is important to understand whether failures from more capable models performing more complex tasks will be bias or variance dominated. Bias dominated failures will look like model misalignment, while variance dominated failures will resemble industrial accidents.”

Discuss