sort of. Stephen Wolfram is well known for his development of an experimental approach to computation. His latest attempt to show that everything can be explained using rules is a long and detailed examination of what computation means. And on the way what NP=P or not is all about.

Wolfram’s post is far too long to be sure that there isn’t a hidden gem in there somewhere, but I’m 99.99% sure that there isn’t. So why am I telling you about it? Simply because it’s interesting and someone else might be able to make something of it. At the very least it would make a great project.

The first thing to say, is that Wolfram is well known for ignoring the work of others and, some would say, for excessive self publicity. Even so he has a way of inventing new approaches to a topic - althou…

sort of. Stephen Wolfram is well known for his development of an experimental approach to computation. His latest attempt to show that everything can be explained using rules is a long and detailed examination of what computation means. And on the way what NP=P or not is all about.

Wolfram’s post is far too long to be sure that there isn’t a hidden gem in there somewhere, but I’m 99.99% sure that there isn’t. So why am I telling you about it? Simply because it’s interesting and someone else might be able to make something of it. At the very least it would make a great project.

The first thing to say, is that Wolfram is well known for ignoring the work of others and, some would say, for excessive self publicity. Even so he has a way of inventing new approaches to a topic - although in many ways the new ways are simply rehashes of his early work on one-dimensional cellular automata. Recently, he invented the world "Ruliology" which roughly means the space of all possible rules, which of course rules everything. Getting something good out of this approach is, however, more difficult than just coining a new term.

His most recent post on the subject is:

P vs. NP and the Difficulty of Computation: A Ruliological Approach

If you read it you will discover that it has much to say about the difficulty of computation and not much about P vs NP. The basic idea is that you can setup a simple model with Turing machines restricted to a number of states, s, and the number of symbols that they can work with k - T(s,k). If you keep s and k small then the number of Turing machines of that type is also relatively small, even if it grows very quickly. For example, T(1,2) has only 16 machines and this means that you can ask what do they compute and draw diagrams of their computation:

This is, of course very reminiscent of the way he classified one-dimensional cellular automata, but the difference is that it is much more difficult to classify the behavior. Reading the output of the machines as integers, we can interpret them as computing integer functions - the input is the initial state of the tape and the output the final state of the tape. Looking at the outputs they are surprisingly regular:

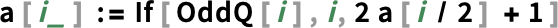

What might be even more surprising is that the function generated often have closed form expressions:

But is this really so surprising? The regularities that we recognize are likely to be the regularities that we invent ways of expressing.

As the size of the Turing machine is increased, the number of them rapidly becomes too many to handle. Even so, Wolfram looks at the low-order machines and finds that there are multiple ways of computing the same integer function. That is, multiple T(s,k) compute the same integer function. This means we can ask questions about which machine is most "efficient" - in terms of time and space used.

Here what it all means becomes increasingly difficult to work out. In one example it seems that there are functions which compute a function in constant, linear and exponential time. As the number of machines is small we can also determine lower bounds for computation within this class of Turing Machines.

Moving up to T(3,2) machine gives us 2.99 million machines, of which 1.45 million halt and about 18,000 functions that they can compute. There are also 13,000 machines that compute a function that no other machine computes. All of this reflects on Wolfram’s notion of computational irreducibility, which is where a computation cannot be computed faster and cannot be reduced to another computation. In this case, the only way to discover what it does is to compute it.

The final part of the exposition goes into nondeterministic Turing Machines and tries to reason about P and NP. Another way of saying P = NP is to say that for every NP machine that computes a result in P, there is a P machine. A great deal of empirical evidence is presented and a sort of conclusion:

"I had always suspected that the P vs. NP question would ultimately get ensnared in issues of computational irreducibility and undecidability. But from our explicit ruliological explorations we get an explicit sense of how this can happen. Will it nevertheless ultimately be possible to resolve the P vs. NP question with a finite mathematical-style proof based, say, on standard mathematical axioms? The results here make me doubt it."

This seems to suggest that P vs NP might be undecidable - a result that doesn’t seem to sit well with the fact that there are NP complete problems. Wolfram is of the opinion that P vs NP is an "infinite problem" of the same type as, say, the Goldbach Conjecture, but it isn’t. If you can prove that an NP complete problem is solvable in P then P = NP; if you can prove that it cannot be in P then P! = NP. Is this an infinite problem?

To know more about this topic, see NP Complete an extract from my book ***The Programmer’s Guide To Theory ***which sets out to present the fundamental ideas of computer science in an informal, and yet informative, way.

More Information

P vs. NP and the Difficulty of Computation: A Ruliological Approach

Related Articles

Programmer’s Guide To Theory - NP Complete

Goldbach Conjecture - Closer to Solved?

Wolfram Language The Key To The Future?

To be informed about new articles on I Programmer, sign up for our weekly newsletter,subscribe to the RSS feed and follow us on Facebook or Linkedin.

Comments

or email your comment to: comments@i-programmer.info

<ASIN:B01N1I83V8>

<ASIN:1871962439>