by Jonathan Kujawa

One common theory of intelligence is that it is an emergent phenomenon. One-on-one, termites aren’t exactly geniuses. But get enough of them together, and they build incredibly elaborate communities that can be 30 meters across with sophisticated ventilation systems to control heating and cooling. And these communities can last for thousands of years.

It’s a bit of a mystery how this happens. After all, even the Fr…

by Jonathan Kujawa

One common theory of intelligence is that it is an emergent phenomenon. One-on-one, termites aren’t exactly geniuses. But get enough of them together, and they build incredibly elaborate communities that can be 30 meters across with sophisticated ventilation systems to control heating and cooling. And these communities can last for thousands of years.

It’s a bit of a mystery how this happens. After all, even the Frank Lloyd Wright of termites doesn’t know how to keep a towering nest from falling over, or the physics of passive HVAC design. Heck, they probably aren’t even aware of the far side of their nest. Nevertheless, amazingly, termites as a collective have evolved to do something far beyond their individual capabilities.

Similarly, our individual neurons are each busy doing their own thing. They are responding to inputs and communicating with neighbors. From these simple cells and their many interconnections arises something greater than the sum of the parts: a person who can paint, create music, tell jokes, and build skyscrapers [1].

It is a founding dogma of the current AI bubble that scale is all you need: with enough data, computational power, and dollars, all you have to do is sit back and let super-intelligence emerge from the digital soup. Not really, of course. Progress in AI also involves a good dose of intelligent design.

Remarkably, sometimes you don’t need evolution or intelligent design. Mathematics shows us that structure becomes unavoidable if the scale is large enough. It’s a bit like those Magic Eye posters that were all the rage in the 1990s. It first looks like pure chaos, but if you look closely enough, you’ll find that it contains order:

Order within Chaos

Order within Chaos

This phenomenon shows up early in a math student’s studies. Very early on, they learn about something called the “pigeonhole principle”. Here, pigeonhole refer to the small cubbyholes you find in the Post Office. If you have 100 cubbyholes, once you have enough letters, two or more of them must end up in the same mailbox. This happens no matter how cleverly or chaotically you place the mail. Without knowing anything about how you place the mail, a bit of information unavoidably emerges once the number of letters grows large enough.

Pigeonholes

Pigeonholes

As simple-minded as it is, the pigeonhole principle can be used in all sorts of fun ways. It tells us that in a large enough forest, two trees must have the same number of leaves. Two people in Italy must have exactly the same number of hairs on their body. In fact, there are two Italians with the same gender, same handedness (i.e., left-handed or right-handed), and with the same number of hairs on their body.

The pigeonhole principle tells us that if you have 367 people in a room, then two of them must share a birthday [2]. My home city has ~60,000 people — more than enough to be able to say with certainty that there are two people who share the same birthday and birth year.

Speaking of birthdays, imagine you are hosting one. You’ve decided that a good party either needs lots of mutual friends or lots of mutual strangers. You don’t want the party to be in the awkward middle where everyone knows a couple of people, but also won’t meet anyone new. For simplicity’s sake, let’s say that a pair of people are both friends, or both strangers; no mere acquaintances allowed. How many people should you invite to have a group of three people who are all friends, or all strangers?

Again, this is a question about emergent structure. You can probably intuit that with a sufficiently large crowd of friends and strangers, it becomes impossible to avoid a group of three at some point. In fact, while a party of five can avoid a group of three friends or strangers, any party with six or more people must have such a group. It is one of those surprising consequences of the pigeonhole principle [3].

Again, this is a question about emergent structure. You can probably intuit that with a sufficiently large crowd of friends and strangers, it becomes impossible to avoid a group of three at some point. In fact, while a party of five can avoid a group of three friends or strangers, any party with six or more people must have such a group. It is one of those surprising consequences of the pigeonhole principle [3].

This problem is the beginning of Ramsey theory. It is a rich area of math devoted to the problem of understanding when order and structure inevitably arise in large — sometimes very large! — systems. It is used in the study of very large data sets, computer and social networks, and the like. It wouldn’t surprise me if Ramsey theory had useful things to say about modern AI systems and their massive neural networks. After all, compared to the internet and social media, the party people is a very small social network, yet we have already seen structure begin to emerge.

Ramsey theory is a rich area of study that we’ve already touched on here, here, and here at 3QD. The reason I bring it up yet again is that we continue to make remarkable new advances, and I wanted to mention a few of them. I learned about this progress in a preprint released by Robert Morris a few days ago. Dr. Morris gives a very nice survey of the current state of the art. Another is this paper by Stanisław P. Radziszowski, in which Dr. Radziszowski summarizes what is known in specific cases.

The original Ramsey theory problem is a souped-up version of the party problem. How many people do you need to invite to a party to ensure there is a group of k people who are either all friends or all strangers? A century ago, Ramsey proved that if the party is big enough, then no matter what relationships they have to each other, a group of k friends or strangers must exist. For short, we write R(k,k) for the smallest party that has a group of k friends or k strangers. The value of R(k,k) is called a Ramsey number. The party problem shows that R(3,3) is 6. We know that R(4,4) is 18.

Amazingly, even today, we don’t know R(5,5). How many people must you invite to ensure a group of five strangers or friends? Nobody knows! We know it is 43, or 44, or 45, or 46. We know 46 is enough, and 42 is too few, and that’s about it. You would think that we could just have a supercomputer work through the possibilities. Unfortunately, the number of possible relationship combinations that would have to be checked is comparable to the number of grains of sand on all the beaches of the world.

And, of course, this also means something like R(10,10) is hopelessly out of reach by any sort of brute force calculation. Dr. Radziszowski tells us R(10,10) is somewhere between 798 and 23,556. The number of possibilities exceeds the number of particles in the universe.

So what can we say? 80+ years ago, it was shown that R(k,k) is smaller than 4k. For example, that means R(10,10) is smaller than 410= 1,048,576. In 2023, Dr. Morris and his coauthors made a significant improvement by showing that it is in fact smaller than (3.8)k. For example, this shows R(10,10) is smaller than (3.8)10= 627,822. Still way off from the true value, but a vast improvement!

In September, Fabrizio Tamburini released a paper that studies Ramsey problems from the quantum computing point of view. Because they are so hard to brute force by classical computers, computing Ramsey numbers like R(5,5) is a good playground for people looking for quantum advantages. Dr. Tamburini shows that you would need about 1,000 qubits to brute-force the computation of R(5,5). That is perhaps just coming into the range of what we can currently build. Perhaps in a few years, we might have the actual value. In the meantime, Dr. Tamburini gives a statistical model that doesn’t compute R(5,5) directly, but does give evidence towards which value is most probable. It could be run on a quantum computer with far fewer qubits, but even running it classically gives good evidence that R(5,5) is 45.

Instead of computing specific Ramsey numbers, you could ask what happens to R(3,k) as k gets larger and larger. This is the party where you want either a group of 3 friends or a very large group of strangers. Which would be a strange party to host, indeed! It’s been known since the 1980s that R(3,k) is smaller than k²/log(k). Just last year, Hefty, Horn, King, and Pfender released a preprint showing that R(3,k) is bigger than (1/2)k²/log(k). Of course, when k is very large, that means you are between 1 and 2 billion, or 1 and 2 googolplex. That seems like a huge gap, but in this business, that is almost as tight as you could hope for.

The paper by Hefty and co., uses a strategy that you frequently see in this area of research. To show a lower bound, you need to show that there are examples that still don’t have the structure you are looking for. In the original party problem, that meant finding a party of five people without a group of three friends or three strangers. Hefty and collaborators don’t actually find an example (the situation is impossibly large).

Instead, they show that if you randomly select a configuration, the probability it has what you’re looking for is more than zero. If there is a chance it could happen, then it must be out there somewhere, even if you can’t find it. After all, if it was impossible, then the odds of finding it would have to be zero.

Very clever!

This probabilistic approach was invented by Paul Erdos. It has proven extremely powerful. The trick, of course, is to be smart about how you “randomly” choose your configuration. If you do it blindly, you are unlikely to be able to say anything useful about the chance that it has what you’re looking for. But if you’re careful, you can choose randomly but not blindly.

Last July, Ma, Shen, and Xie released a preprint where they used this strategy. They show that R(k, 52k) is at least as big as p-k/2, where p is an explicit number between 0 and 1/2 that depends on 52. In fact, there is nothing special about 52 here. Pick your favorite number. Their result applies equally well to R(k,7k), or R(k,42k), or whatever it might be.

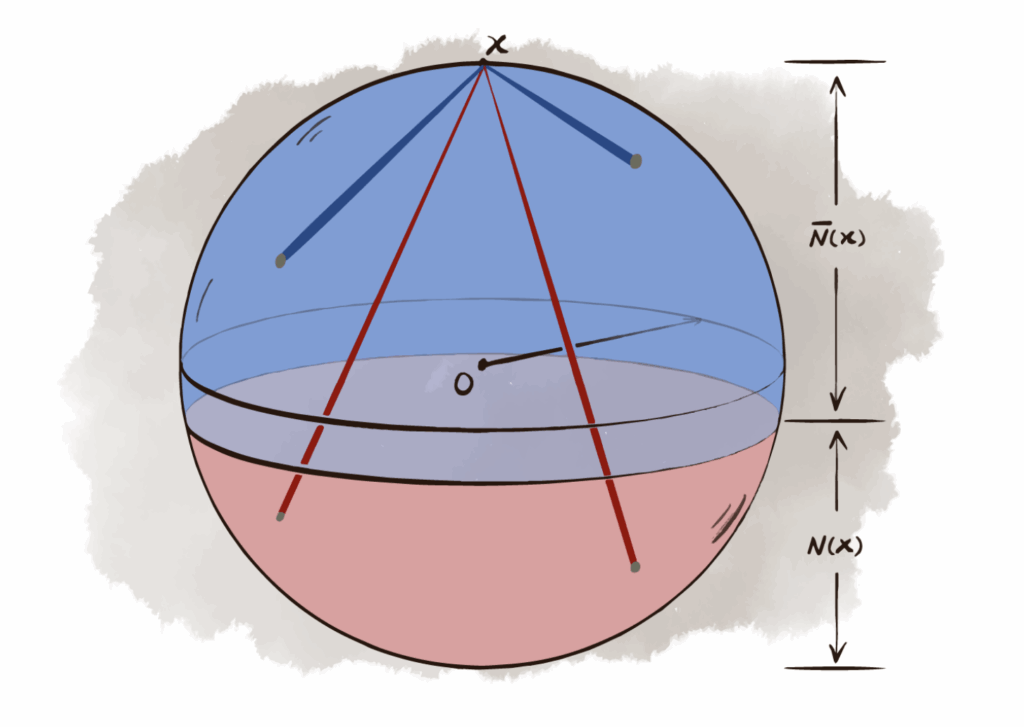

The clever trick in the paper by Ma, Shen, and Xie is to first randomly place the people on a sphere, and then, for each pair of people, you imagine one of them is at the North Pole. If the other person is close to the South Pole, they are a stranger. Otherwise, they are friend. The number 52 (or whatever you’ve chosen) determines where the cutoff between a friend and a stranger lies. Here is a picture from their paper illustrating how it works (blue means friend, red means stranger):

Friends and Strangers

Friends and Strangers

The geometry of the sphere lets them keep a handle on the myriad relationships between the millions, billions, trillions, or more people at your party.

If you’d like to learn more about what we know about estimating Ramsey numbers, both the preprint by Dr. Morris and the paper by Dr. Radziszowski are worth checking out. If only to marvel at how much we know, and the equally huge gaps that remain.

In writing this essay, I was led to wonder if AI could help find new examples for Ramsey numbers. Last year, I saw an interesting talk by Geordie Williamson about his collaboration with DeepMind to use AI in math research. He and his collaborators, along with others, have shown that AI can be remarkably good at finding examples. In much the way AI can teach itself chess and come up with unexpected strategies, you can use a similar strategy to search for examples in math. If you gamify the problem by rewarding the AI for finding examples closer to what you’re looking for, you can let it develop strategies for searching through the space of possibilities in a quest for maximizing its score. Geordie and his collaborators used AI to find a wealth of new examples in their situation, and I bet something similar could work here, as well.

***

[1] In fact, this phenomenon doesn’t stop there. After all, no individual human has the knowledge to design a skyscraper down to its smallest nuts and bolts. The best architect still needs the help of designers of electric motors for elevators, experts in the chemistry of concrete, modelers of wind flow, and countless others. Our own society and all that we accomplish emerge from the actions of individual humans. We’re just more advanced termites.

[2] In fact, if you’re okay with playing the odds, already in a group of 23 or more people, the odds that two share a birthday are better than 50-50. This is the famous Birthday Problem.

[3] To see that six is enough, pick one person (let’s call them Anne-Marie) and think about their relationships with the other five. Since there are five relationships and only two possibilities (strangers or friends), the pigeonhole principle says that at least three of them must all have the same relationship with Anne-Marie. That is, there are three who are friends with Anne-Marie, or who are strangers to Anne-Marie. Let’s say all three are friends with Anne-Marie. If any two of them are friends, then those two plus Anne-Marie form the triple we’re looking for. If none of the three are friends, then all three are strangers. Again, we have the triple we’re looking for. (Remember, all we promised was a triple of friends or a triple of strangers.) And you can apply the same line of thinking to the case where all three were strangers to Anne-Marie. In any scenario, there is a trio of friends or a trio of strangers.

The question remains if we really need six, or if five party people would have been enough. But with a little trial and error, you find you are able to avoid a triple if you make just the right combination of friends and strangers among five people.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.